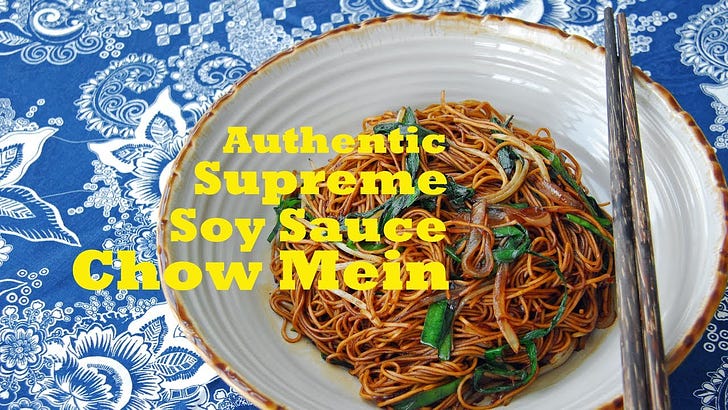

Soy Sauce Supreme Fried Noodles (豉油皇炒面)

I.e. The original (or, 'one of the originals') Cantonese Chow Mein

So we wanted to show you guys how to cook a Cantonese fried noodle dish – Supreme Soy Sauce Fried Noodles - that I think you’ll quite like. Generally, people seem to have two major complaints with Chinese fried noodles – expats in China will sometimes find them quite oily (and we’ll talk a bit about why later), and people abroad often get an overcooked, gloopy chow mein. If you use these Cantonese techniques though, you’ll get a really tasty, perfectly cooked noodle with… very little oil.

Ingredients

Cantonese Egg Noodles, 100g (蛋面). Take a look at the consistency in the video. What we’re using are fresh ones (which are generally much easier to work with), but dried ones could also work in a pinch. We’ll discuss the differences in cooking times and such when we go over the process. If you’re abroad, I’ve sometimes seen these called ‘Hong Kong Chow Mein Noodles’.

Jiucai, “Chinese Chives”, 50g (韭菜). Cut these up into 2 inch long sections. There’s going to be a harder portion right by the root, just toss that.

Bean Sprouts, 70g (芽菜). Something we like to do to prep bean sprouts is to prepare them into ‘silver sprouts’. To do so, you’re going to take your bean spout, and pull off the little mungbean at the top and the small root at the bottom. This is a little bit of a pain if you got a huge batch, but really improves the texture of the beansprout – instead of having the little chewy bits at the end, you’ll get a nice evenly crunchy beansprout. You don’t have to do this of course… most of the time, you’ll only see this in China in higher end restaurants or old Cantonese eateries that keep on with the older traditions. This yielded about 40g of ‘silver sprouts’ for us.

Half of a Shallot (干葱). Dice this up. If you’re in China or elsewhere in Asia you might be only finding those small shallots on the string – if using those, use one whole one.

Quarter of a White Onion (洋葱). Sliced.

Ingredients for your Sauce:

Boiling Water, 5 TBSP. In the video, we just used the boiling water from the noodles.

Sugar, 1 TBSP. Take your sugar and dissolve it into the reserved hot boiling water, giving a healthy stir. We’re just using boiling water here to make the sugar dissolve easier.

Dark Soy Sauce, 1 TBSP (老抽). This is going to form the base of the sauce and the flavor of the dish.

Light Soy Sauce, 2 tsp (生抽). If you watch the video, no… your eyes aren’t deceiving you – we put a TBSP in originally. However, it was slightly on the salty side (I have a high tolerance for salinity so I personally was fine with it), so with a later run at it we reduced the light soy sauce a touch and it was perfect.

Sesame Oil, 1 tsp (香油). Toasted of course.

Thick Soy Sauce, ½ TBSP (酱油膏). This was one of two less conventional ingredients that Steph ended up using based off an interview that she read with a cook from one of our favorite restaurants in Hong Kong. It’s a thick, sweet, soy sauce that’s really popular in Taiwan, but you can find it in most large grocery stores in Mainland China. If you’re outside of China and can’t find this, the Indonesian Kecap Manis should also work great. And if all else fails, just sub in Oyster sauce.

Fish Sauce, ½ tsp (鱼露). Also a touch unconventional for this dish, but works really well. While you probably associate Fish Sauce with Southeast Asian food, it’s a rather common ingredient in Guangdong and is especially used quite a bit in Chaozhou cooking (also used in Shandong but called xiayou - 虾油). We used a Vietnamese fish sauce though, because Vietnamese fish sauce has a real deep umami flavour and is thus outrageously awesome. We didn’t test the Chinese or Thai varieties (which seem to have a sharper saltiness to them), so if that’s what you’re using knock it down to ¼ tsp at first to be safe.

Process

Prep your veggies. Cut the jiucai (“Chinese Chives”) into sections, dice your shallot, slice the onion, and (if doing so) prepare your silver sprouts.

Cook the noodles. Before you toss your noodles in, take 5 TBSP boiling water for the sauce in step #4. Now, for fresh noodles like the ones in the video, we’re cooking them for exactly one minute in boiling water – move them around with chopsticks or tongs to make sure they don’t clump together. If you’re using dried, cook them according to the package (different dried noodles may use different times) until al dente - likely ~30 seconds before ‘done’ on the package. Chinese cooks will usually know dried noodles are al dente once the noodles start to loosen up and become individual ‘noodles’ (you can get a visual at 2:50 in the video), but if you know your pasta you can use the western method to figure out doneness as well.

Rinse, drain, and cover your noodles. Once it’s finished, in a colander rinse your noodles thoroughly under cold running water to stop the cooking process. Then, try to drain as much water out as you can. There’s still going to be a tiny amount of residual heat/steam from the noodles, so one trick is to take a paper towel and cover the noodles with it to make a nice little ‘lid’ of sorts. You can get a visual at 3:20 in the video. This is going to help the noodles cook evenly, as the residual heat is going to continue to cook any slightly undercooked noodles.

Prepare your sauce. Whisk in the sugar into those 5 TBSP of boiling water that you reserved. Then add in the rest of the ingredients for the sauce and give it a mix.

Sweat the jiucai and the bean sprouts. What we’re doing is lightly ‘toasting’ these ingredients over medium heat with zero oil. This technique is called baiguo honggan, and the idea is the quite similar to sweating vegetables in Western cooking - we want to get out some water content from the vegetables. For the jiucai, sweat for about two minutes until slightly wilted, being sure to move them around with chopsticks or tongs so that the jiucai doesn’t wilt into a big pile. For the bean sprouts, sweat for one to two minutes, until the edges of the bean sprout turn slightly brownish.

Oil your wok using the longyau technique. I’m separating this into a separate step, but we’re going to be doing this three times over the next three steps. The longyau technique is this: get your wok nice and hot over a high flame, pour some oil and swirl it around to coat the wok and get a nice non-stick surface, and then pour out any excess oil. The amount of oil that we drain will be different for each ingredient. We’re not going to drain any oil before frying the shallots, drain basically all the oil except for that coating when we fry the onions, and drain most of the oil – keeping about ½ TBSP in the pot – when frying the noodles. The visual for this is at 6:20 in the video.

Fry your shallots. Oil the wok using the longyau technique without draining out any oil, then add in your shallots. Fry for a couple minutes over medium heat, and take them out once they’re nice and brown. Drain the oil into a bowl and reserve for step #9.

Fry your onions. Oil the wok using the longyau technique and drain out all the oil except what’s lining the pan. Fry for a couple minutes over medium heat, then take them out.

Fry your noodles. Oil the pan using the longyau technique and drain out most of the oil, but keeping about a ½ TBSP in. Use the drained shallot oil here as it’ll lend a real nice flavor. So, you have a choice here – if you’re afraid of the noodles sticking to the wok, you can always leave a little more oil in… but you’ll end up getting an oilier end result. Fry the noodles for about 30 seconds on medium or even medium low heat (if on a Chinese range), then add your onions back in. Give them quick stir together.

Add your sauce and reduce it in the noodles. Take a look at 9:21 in the video for a visual. Move your noodles around to absorb some of the sauce as it reduces. After a minute or so, add back in the remainder of the ingredients – the jiucai, the beansprouts, and the shallots. Stir these around for a few minutes as the sauce reduces. Once you have no real visible liquid pool remaining at the bottom of the pot, it’s done and ready to eat.

A note on technique:

Something that you’ll notice about Cantonese stir-fried dishes is that in general, they’ll tend to cook each ingredient separately to their desired doneness – then all added back together at the end. On the street and in many homes in China, you’ll see people just dump in all the ingredients at once and fry everything together. The latter style is called xiaochao (‘little stir fry’), and is really convenient once you nail it but… it can be real variable and your timing needs to be perfect. If you’re just getting started cooking with Chinese food, an ingredient-by-ingredient Cantonese stir-fry has a much smaller learning curve.

If you’ve never seen someone doing xiaochao, here’s a video of a dude on the street making some noodles. As you can see, it can look real impressive – especially if you’re doing it over a jet engine flame.

I love xiaochao like anyone, but for starchy things like fried rice and noodles… Cantonese technique is going to be really preferable I think. Here’s the thing - if you try doing xiaochao with a noodle dish, what’s gunna happen is your aromatics and veggies will suck up your oil, leaving a dry pot for the noodles to just get stuck on. To compensate, many cooks will just dump a mountain of oil into the pot which will prevent sticking but will make it super oily. I mean, just look at that Shanghai street food video – that guy uses like over ½ cup oil for one bowl of noodles, probably ten times or so the amount we use here.

Cantonese people will traditionally judge a place’s noodles by what the bowl looks like when you’re done eating. If there’s a bunch of sauce or a ton of oil at the bottom of your bowl, it ain’t a good fried noodle.

A note on ingredients:

This noodle dish is called ‘supreme soy sauce fried noodles’ and as such the flavour should be all about the soy sauce, and the dish should be all about… the noodles. This is my big gripe with a lot of American-Chinese food – they’ll take a fried noodle dish and add a bunch of bizarre ingredients to it (plus zucchini? No thank you!).

If you really want, you could take some julienned chicken, pork, beef, or char siu and add it in – but just remember, it should all be about the noodles. If you wanna eat more meat, make a meat dish to go along with it!

If you’re in the USA or somewhere and thinking to yourself ‘could I… just use spaghetti’? The answer from us is an emphatic… probably? Honestly, if you lived somewhere where you had access to (A) really awesome freshly made Western-style pasta or (B) sub-par dried egg noodles, I’d lean towards option A. Here’s the thing though, some of the process might be a touch different – we might be able to give a couple tips, but you’ll probably need to take that journey yourself.

Lastly, notice that we’re not putting any cornstarch in. Gloopy sauces have their time and place, but it ain’t here.