What's better on a hotdog, Thai or Chinese food?

An overly in-depth, mildly unhinged analysis.

So as you might know already, we live in Bangkok - specifically, the Chinese expat haunch of Huai Khwang. Steph’s away in China for a couple weeks to sort our upcoming move; my best friend here Adam is away for a couple weeks to watch his fiancé compete in the Chicago marathon.

I’m bored. I need some sort of small project to keep my mind busy, prevent my brain from succumbing to the hypnotic siren song of roguelike deckbuilders. Luckily, the day before Steph left, we went to the Sukhumvit Ikea, where I was deeply impressed by a suspiciously-cheap deal on hotdogs. And so, with a surplus of low-grade Ikea dogs in hand, with this post I wanted to try to answer question that’s been rattling around my head for the last couple of years:

What’s better on a hotdog, Chinese food or Thai food?

Now, with this post I want to focus on ‘authentic’ Chinese and Thai food as hotdog-topping-candidates – ‘authentic’ meant solely as a descriptor, and not a statement of judgement. I harbor no ill will towards Crab Rangoons or Thick Curries of Various Colors – I like eating the stuff too. I guess I’m just assuming that the normie version of this experiment probably already exists somewhere within the deep web of the Good Mythical Morning back catalogue, and wanted to see a more thorough culinary investigation.

A brief introduction to xia-hotdog-ability

So there’s a concept in Chinese cuisine called xiafan (下饭) – an adjective that literally just refers to how well a food goes with rice. In my recipes, I usually translate the term as “over rice” dishes; Fuschia Dunlop translates it as “send-the-rice-down” dishes. Which you prefer probably depend on ol’ fidelity vs transparency tradeoff in translation – the Dunlop translation is a little awkward, but definitely more closely captures the meaning of the original Chinese. A xiafan food most accurately refer to something that can assist you in the project of eating… lots of rice.

Now, if you’re anything like me? I think that concept can feel borderline alien to the modern Westerner (thus my low-fidelity floozy of a translation). After all, most of us grew up in a post-Atkins world. Even for those that aren’t diabetic, or on the whole keto or low gluten train… there’s still this overall cultural sense that starches are something bad for you. Like sugar, they’re something to be minimized – a special little treat. Many westerners might be on the lookout for things to help in the project of eating vegetable; or perhaps if you’re a bodybuilder trying to bulk, and you need to figure out ways to down ever-increasing quantities of canned tuna. But starch? Piling on some extra rice or bread is something that you do on a holiday – you certainly don’t need help eating them.

Of course, for a lot of human history however, the situation was pretty much the reverse. Rice was something that basically everyone had, unless times were particular bad. It’s how you got full. Your staple grain was something that you ate every day - and so, it was also something that was incredibly easy to get bored of. So especially on the lower end of the income spectrum, a lot of foods in China at least could be conceptualized as strategies to combat that boredom – that sensory-specific satiety.

But I believe that that same dynamic extends way past China, much further than rice. Once you start viewing cuisine through the lens of xia-[starch], you can start to see it absolutely everywhere:

Lao food and Northern Thai food are super xia-sticky rice.

Northern Chinese meals can be centered around stuff that’s xia-mantou.

Ethiopian food is very much xia-injera.

Old school western stews and such definitely strike me as xia-crusty-bread.

Mexican homecooked meals are quite obviously xia-tortilla

Which brings me to a postulate – if a food is extremely xia one starch, it’s a reasonable candidate to xia a different starch.

Because I think if we’re honest with ourselves, most of us in this room likely have an unholy desire to mash up foods from across different cultures. A remix can often be a good bit more fun than a cover. And a starch swap? Can be a fantastic starting point - though obviously not guaranteed to work one-for-one. For example, in my experience, I’ve found that Chinese xia-rice dishes are super xia-injera; Northern Thai and Lao xia-sticky rice dishes tend work pretty well with tortillas.

Which now brings me to the hotdog.

Now, a hot dog is not a sandwich, but it is a ‘sandwich-like-object’: something where a hunk of protein (or vegetable, but usually protein) is nestled into the starch itself and consumed in the same bite. A baozi is a sandwich-like-object, ditto with a fish taco. When it comes to xia-[starch]-ability, sandwich-like-objects can behave similarly to staple starches, but there are subtle differences:

Sandwich-like-objects usually contain pre-seasoned proteins. This makes it less demanding, flavor wise. A xia-rice dish often needs to bring, at the very least, a good bit of salt along for the ride.

Sandwich-like-objects need a certain structural integrity. When you eat a meal xia-[starch], the dish itself can be super loose, runny, and saucy, as you’re combining the elements on a bite-by-bite basis. Sandwich-like-objects need a package – you don’t want the thing itself dripping like crazy on your fingers. While there are definitely abominations like the Sloppy Joe, frankly the thing would be way, way better to eat bit-by-bit with a mantou or even a slider roll. The fact that we don’t speaks to the deep structural issues within western civilization today.

I love eating around the world – it’s probably the thing in life that I enjoy most. But I’m also an American, and hotdogs are in my blood.

I… need to know.

Candidate #1: Thai Pad Kaprao (ผัดกะเพรา)

Alright, we’re starting things off with what’s probably the most obvious possible candidate – the true national dish of Thailand: Pad Kaprao. This spicy, holy-basil-y, oyster-saucy stir-fry is available practically everywhere in Bangkok – there’s a small eatery that serves up a good one literally a 90 second walk from by front door. Logical place to start, and I mean… this has to work, right?

… it works. Because I mean, of course.

It’s a little on the salty side (it’s meant to go with rice, after all), but this would be easy to correct if you were cooking for yourself.

Xia-hot-dog rating: Very good

Better with hot dog than rice?: I would put it as ‘similar category as rice’ – for me, personally. I’ve always liked the flavor of Pad Kaprao, but the spicy fresh chilis can sometimes get a little intense if eating it in quantity with rice (though a fried egg rackets things up, for me). The heat blends quite well within the context of a hotdog. Of course, Pad Kaprao-with-rice is practically a food group in Bangkok, and I’m not arrogant enough to think that it could get dethroned from just one tasting. Plus, again, it is a little on the salty side.

Candidate #2: Yunnanese Fermented Tea Leaf Salad (茶叶豆)

Okay, we’re going the other direction on the mainstream-niche scale here, I know. I promise for my next Chinese dish I’ll get a little less quirky.

This will take a touch of explaining.

You see, my (aforementioned) neighborhood of Huai Khwang is generally thought of as the Flushing-equivalent of Bangkok - i.e. the ‘New Chinatown’. This is why this specific slice of geography is probably the second best place in the world to perform this experiment after Queens. But it’s actually sort of a misunderstood area – it’s often characterized as a ‘Chinatown’ with ‘Chinese Immigrants’, but… Thailand doesn’t have immigrants. It has expats and travelers.

The main drag of Huai Khwang – Pracha Rat Bamphen road – is a motorcycle-clogged three lane street with narrow sidewalks lined with milk tea shops and guesthouses. In spite of the swath of conveyor belt hotpot joints that seem to be a smash hit with Bangkok locals, there’s otherwise a transience in the air here. It’s less of a modern-day-Chinatown, more of a cross between Khao San Road and Sukhumvit, albeit with Chinese characteristics – a gathering point for backpackers, grifters, businessmen, money changers, digital nomads, and whoremongers. The usual Bangkok scene, with, perhaps, an important distinction – the Yunnanese.

While Thailand is not an immigrant country (they closed their borders back in the 1940s), in the 60s they… made an exception. At the time, the country was battling a Communist insurgency in the North, and quite conveniently, right across the border in Burma was an army: remnants from the KMT, who had since turned into one of the world’s premier heroin smuggling outfits.

To drastically simplify the tale, they were welcomed into Thailand in exchange for doing a bit of the central government’s dirty work in the north, though in the 80s they were forced to hand in their guns and find a different line of work. Ethnically, the group was (generally) Han Chinese hailing from west Yunnan, particularly around the mining town of Tengchong. These days, you can generally find them around the hills outside Chiang Rai and Chiang Mai: in the words of the owner of the barbecue joint here I like to frequent, “you could drive straight North from Chiang Mai into the hills, all the villages are Yunnanese, even after the Myanmar border”. Probably a slight embellishment, but only just.

But as cross-border trade and travel between China and Thailand exploded in the 00s and 10s, the Yunnanese found themselves in an interesting position. After all, unlike the older generations of Thai-ified Thai Chinese, the Yunnanese were fluent in Mandarin Chinese. And so, in Bangkok, as a soapy massage scene grew around the Chinese and Korean embassies in Huai Khwang, the area became increasingly staffed with Mandarin-speaking Yunnanese from the North. And being Thai citizens, they also had another benefit – unlike Chinese expats, who need a Thai partner for their businesses (like all foreigners do) – they can open up companies themselves. And so, in Huai Khwang, many of the tourist-facing restaurants are owned and operated by… them.

Of course, like many tourist-facing restaurants, a good chunk of them aren’t really worthwhile. The Northern Chinese fare is usually quite bad. The Sichuan food is better, but quality varies wildly between restaurants. But tucked on a lot of these menus, if you know where to look, is some fantastic west Yunnan food.

Case in point being the aforementioned barbecue restaurant. If you take care to order the Yunnan food, you’re in for a treat – some fun stuff on that menu.

This is Yunnan chayedou (茶叶豆), a west Yunnan specialty of fermented tea leaves. If ‘fermented tea leaves’ rings a bell, it’s for good reason - it’s an incredibly iconic Burmese dish, and quite obviously came to west Yunnan from that direction. Compared to the Burmese style, the Yunnan style really loads it up with cabbage and fresh chili pepper. I prefer the Burmese sort, but the Yunnan style can go quite well next to some barbecue, a bowl of rice, and an ice cold beer.

So how is it on a hotdog?

… it works, 100%.

Xia-hot-dog rating: Very good

Better with hot dog than rice?: Definitely, but then again… chayedou is probably more xia-liquor than anything. I probably should’ve done something more classically xia-[starch] as my second dish here - kind of dropped the ball re adhering to the underlying concept of the activity. I’ll make sure I’ll be more judicious with future candidates, I guess I was just curious.

But yes, this is very good on a hotdog. The Burmese one would probably be even better, but you might need to get careful about salinity.

Candidate #3: Mala ‘Salad’ (麻辣菜)

From the same Yunnanese restaurant. In that corner of the country and into Burma, there’s a dish called Malacai (麻辣菜) – basically just mixed vegetables in a sort of mala numbing-spicy dressing. If you come into the dish expecting Sichuan mala flavors, you might be slightly disappointed, as malacai usually relies on packaged hotpot base as a main flavor. It’s tasty, but it’s intensely spicy and - in my opinion, at least - a little one note compared to what you’d find in Sichuan.

Still, I feel like this is a good way for me to sidestep Mapo Tofu, which (1) is probably the most obvious Chinese candidate to xia-hotdog and (2) I’m frankly a little sick of (I’ve eaten a lot of Mapo in my life). Plus, Andrea Nguyen already covered this ground, and if you’re not going to trust Andrea Nguyen, I’m not sure who you can trust.

I also get to kill two birds in one restaurant this way:

Awesome, actually. Better than Mapo Tofu would be I think (which would likely have some structural integrity issues?), but that might be partly due to Mapo disillusionment.

Xia-hot-dog rating: Excellent.

Better with hot dog than rice?: Honestly? I think it might be. Maybe someone that’s a bigger fan of the dish might answer differently, but this might actually be the best case scenario for malacai – especially if you’re consuming the dish sober.

Definitely top tier so far. Let’s move back to Thai food.

Candidate #4: Pounded Chili & Eggplant, Tam Makhuea (ตำมะเขือ)

Of course, the Yunnanese have been in Northern Thailand for over a generation now… so I probably shouldn’t be quite so quick to draw such a clear line between ‘Yunnanese’ and ‘Northern Thai’. Up in the north, Yunnanese do localize – many speak Thai at home. And at the same time, given that Chiang Mai was practically the most popular international tourist destination for Chinese for a spell, learning Mandarin was also quite popular up there. Time has a way of shifting things into greyscale.

So for similar reasons, Huai Khwang is actually one of the better corners to find proper Northern Thai food in the city. Which is quite convenient, because I fucking adore Northern Thai food. My go-to food delivery option on Grab (the Southeast Asia equivalent of Uber Eats) for lunch these days is this place that doubles as a vendor for plastic flip-flops – they do a very nice job, at least to my undereducated taste buds.

Now, the staple starch up in Northern Thailand (a.k.a. Lanna) is historically… sticky rice. The traditional way to eat meals around sticky rice is to form it into a little ball or saucer and use that as a ‘utensil’ of sorts to consume the dish. Here you can see how one of our favorite Northern Thai food vloggers does it:

Steph’s go-to order for lunch is the restaurant’s Tam Makhuea – pounded chili and eggplant. Pretty simple dish at its core, you can see how it’s made here.

So how is it on a hotdog?

Xia-hot-dog rating: Fucking excellent. No qualifications, best so far.

Better with hot dog than sticky rice?: For me personally, I think it might be. I’m a little on the sensitive side to what I call… ‘eggplant mushyness’. Often I find myself using eggplant dishes as more of a ‘sauce’ for my rice/sticky rice, sort of akin to how you’d go at a Baba Ganoush. Which when it comes to this dish, often that functionally means I still have half the dish left by the time I get to the bottom of my bag of sticky rice. This hotdog solution sorts that issue for me.

But like, the dish is also really damn good with sticky rice, and not everyone in the world shares my odd eggplant pickiness. If the dish was Namphrik Num – basically, more or less the same deal as Tam Makhuea minus the eggplant – I wouldn’t be quite so certain.

Still, grade A hotdog topping.

That’s enough backstory for now, I suppose. Let’s try to chew through some hotdogs a bit quicker here…

Candidate #5: Young Jackfruit Salad, Tam Khanun (ตำขนุน)

Same restaurant. My favorite might be a little bit of a white person cliché, but I love it: Pounded Young Jackfruit ‘salad’.

Xia-hot-dog rating: Very good, excellent perhaps.

Better with hot dog than sticky rice?: This one is difficult for me, because I just love it so much with sticky rice.

In the context of a hotdog, it’s quite good but I think it’s… missing something? It’s a touch on the plain side. Maybe a little cucumber would be nice, or perhaps if you added more curry paste to the dish itself it could help things cut through.

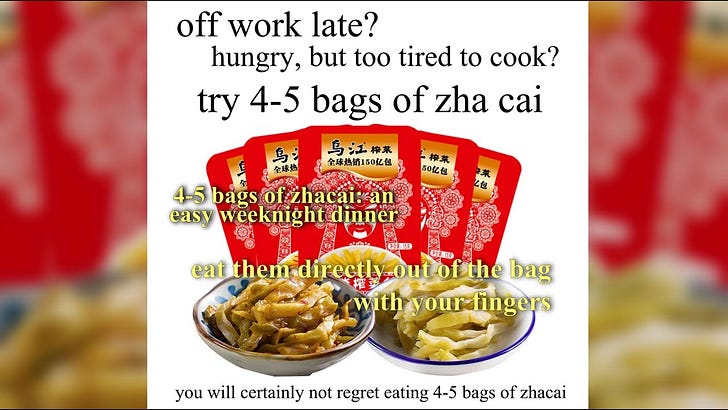

Candidate #6: Zhacai (榨菜)

Next up, Zhacai – perhaps the most stereotypical send-the-rice-down Chinese ingredient there is. So much so that sometimes in China people refer to ‘mealtime videos’ as ‘electronic zhacai’.

Zhacai is the fermented stem of a variety of mustard tuber, with a few variants sprinkled around the country. I’m having the Sichuan-style mala version here (my personal favorite).

This obviously works on a hotdog.

In the future, I think I would want to mince my Zhacai first, as it’s a little ‘chunky’ when eating (I hate when the fillings awkwardly plop out of a sandwich-like-object). It’s a little on the salty side, but Zhacai also has this weird quality where it always tastes pretty balanced, even if the dish contains enough sodium to choke a small family of horses. It’s also a little one-note, but could be easily corrected by making a small ‘salad’ with it with garlic and cilantro, ala this recipe.

This could be phenomenal with a couple tweaks, I think. I don’t think that’s all she wrote when it comes to Zhacai on a hotdog.

Xia-hot-dog rating: Very good, excellent perhaps.

Better with hot dog than rice?: I mean, of course not. Zhacai plus white rice is one of the great food combos in the world – kings cannot be so easily dethroned.

Candidate #7: Tomato and Egg (番茄炒鸡蛋)

Ah… tomato and egg. The dish that seems to be everyone else’s favorite homestyle Chinese stir fry. I’ve never been the hugest fan, but I’ve also slowly started to make my peace with it.

I used to be one of those people overly picky about tomatoes (no skin, no gunk), and have been trying my best to purge those incorrect thoughts.

This is quite good, actually. If you’re someone like me that’s not the hugest fan of the stir fry itself, this might be a pretty useful application. That said, I think it might be particularly good with stewed tomato and eggs – the sort that you’d see up to top Biang Biang noodles and the like.

Xia-hot-dog rating: Very good

Better with hot dog than rice? For me, yes.

Candidate #8: Big Plate Chicken (新疆大盘鸡)

Now, I know this one was a pretty weird choice. For the unaware, Big Plate Chicken is a Xinjiang dish consisting of braised chicken, potatoes, and served with wide, flat, hand pulled noodles. It’s quite delicious, but obviously ‘bone-in-chicken with potatoes’ isn’t exactly a prime candidate for ‘hotdog topping’.

But, we were finishing up a video on Shanxi-style big plate chicken (an interesting dish in and of itself)… and I was missing a bit of B-roll of the Xinjiang style. I was hoping I could re-use some old footage of mine, but it was looking that I’d have to bite the bullet and shoot some more. Fortunately, in Bangkok there’s a solid Xinjiang restaurant called Afanti, run by a family of Chinese Muslims. Also fortunate is that their Big Plate Chicken was… absolutely spot on.

Unfortunately, I’m just a single person… and it is, indeed, a big plate of chicken. It’s one of those dishes that’s really meant to be shared amongst a small family – practically a Cheesecake Factory portion.

And so, I had a mountain of leftovers. And so, why not? Grabbed a couple hunks of chicken, removed the bone, roughly minced it all together.

Oh, it’s actually incredible. Best Chinese thing I’ve put on a hotdog by a country mile.

The flavors just… make sense. The braised fresh chili peppers might have been the highlight, but the whole thing came together. The potato didn’t give me too much of a starch-on-starch feeling.

Xia-hot-dog rating: Fucking excellent.

Better with hot dog than noodles?: Probably not, but that’s mostly a function of just how awesome hand pulled noodles are with Big Plate Chicken. A hotdog is certainly not the worst place a bit of big plate of chicken could end up…

Candidate #9: Chinese Zajiang Edamame from Anhui (毛豆杂酱)

This dish probably takes a little bit of explaining to do.

Recently, I’ve been on a kick of digging around Bilibili and such trying to find recipes and food/travel vlogs specifically relating to the Anhui province. It’s a place I don’t know all that much about – traveled there once when I was 19, but that’s about it. There was a specific dish that I’d been down a rabbit hole looking for information about – something called Zajiang (or Zhajiang) Edamame:

Luckily, in Huai Khwang, nestled amongst the excellent Yunnan restaurants and mediocre Northern restaurants there is, actually, an Anhui restaurant. After all, expats can still open restaurants in Thailand, and these guys are pretty well integrated. They serve up a sort of style of food known as Tucai (土菜) – spicy, working class fare that you can find in the provinces of Jiangsu and Anhui. It’s quite popular among long-term Chinese expats in the neighborhood – the place feels straight out of China, complete with indoor smokers and everything.

It wasn’t on their menu, but I asked them if they could whip me up a Zajiang Edamame. They cautioned that the shrimp wasn’t quite the same here, but happily obliged.

Okay, this is the first dish that definitely doesn’t work.

It’s really salty. Way too salty for a hotdog.

Xia-hot-dog rating: Not good.

Better with hot dog than rice?: I mean, no.

I’m not even sure how much I like this dish with rice – but it’s gotta be top tier drinking food.

Halfway into the dish, I find that I’ve borderline-subconsciously already slugged down a neat 600 milliliters of Singha. I ask the owner if in Anhui the dish is usually thought of as more xia-rice or more xia-liquor – she responds that it’s about 50/50. I guess I’m apparently on the latter team.

It’s a good dish, but fuck, it’s salty. If I owned a brewery in Hefei, I’d give out free plates of the stuff – whatever cost there was to it, I guarantee that you’d make triple in beer sales.

The table next to me looked curiously at my project, and after a brief chat, insisted I also try the Zajiang Edamame with some baijiu. I obliged and knocked back a couple with them, before calling the night quits.

Candidate #10: Isaan Blara Bong (ปลาร้าบอง)

I was stumbling back from the Anhui restaurant, a bit disappointed in my Anhui experiment and a touch on the inebriated side from the baijiu. A perfect state of mind, perhaps, for this:

…one of the world’s great street snacks. Thai fried chicken, sticky rice, and a chili dip to eat with said sticky rice. This particular stall on my alley serves next to a funky chili dip called Blara Bong:

If you’re the type of person that finds fish sauce ‘smelly’, Blara Bong is not for you. It’s based off of a fermented fish called Blara Ton (ปลาร้าต่อน) – the closest western comparable I could think of being Surströmming (I’ve heard that Thais in Sweden sometimes use the brine from Surströmming to sub for Blara).

For me though? I love this shit. It’s like… the food equivalent of math rock. It’s not easy to love the first time you experience it, but it’s undeniably interesting. And after enough reps, you learn to love it.

So how is it on a hotdog?

I tried a thin shmear at first. Pretty damn tasty.

Then I added a little more, and… now it’s way too salty.

I think there’s a ‘there’ there, but this should probably just be a thin spread within the context of other fillings. Maybe some veg might be nice? I can’t think of any obvious routes to take this though.

Xia-hot-dog rating: Okay-ish, but be careful not to add too much.

Better with hot dog than sticky rice?: I mean, for me at least, Blara Bong might be even better with sticky rice than Zhacai is with white rice. So… no.

Candidate #11: Green Curry (แกงเขียวหวาน)

I’m being a little too frisky with my dish selection I think, so I should probably calm down and cover a few more… obvious ideas.

Swung up to a central Thai restaurant – to my (undereducated, again) taste buds, this restaurant serves similar fare and hits a similar quality level as the Michelin Gourmand darlings of Sri Trat and Supaniga down in Sukhumvit, albeit for half the price. It’s always reasonably popular with Thai families in the area, but that may be partly a function of its luxurious quantity of surface parking – a rarity in Bangkok. In any event, they have the classics.

Now, I’m sure green curry’ll be pretty good, but I am a little worried about the consistency. At Thai restaurants in the west, green curry is often quite thick; in Thailand, it’s often thinner and soupier.

To compensate and give the thing a fair crack, I decided to mince up some of the eggplant inside, which is basically a green curry sponge.

This’s gotta be good, right?

Hmm...

Sort of, but not… really? It doesn’t quite come together, almost like two separate dishes inside of the same bun. I guess there’s a reason why hotdog usually isn’t added to green curry. It might actually just be better in the bun without the hotdog.

Xia-hot-dog rating: Edible, for sure.

Better with hot dog than rice?: Definitely not.

Candidate #12: Wingbean Salad (ยำถั่วพู), sort of a ‘Shrimp Tom Yum’ Flavor Profile

While you might not know too much about this specific dish, I promise you’re roughly familiar with the flavors. It’s a salad that leans on a specific combination of Thai Chili Jam (Nam Phrik Phao) and Evaporated Milk that forms the basis of the internationally beloved Shrimp Tom Yam soup. Of course, Tom Yam’s got the same ‘soup’ problem as Green curry, so I felt like this might be a fairer way to test out those flavors.

Plus, I fucking love Wingbean salad. It’s practically a cliché – more than a handful of self-professed food-loving farang expats I’ve chatted with here have wistfully name-dropped this specific dish. It’s good. Hot Thai Kitchen uses longbeans as a sub in her recipe, you should try it sometime.

This’s gotta be awesome.

Hmm.

I mean, I still love the flavors itself, but I think I’ve might’ve figured out now why I didn’t love green curry either. Because munching down on the wingbean-salad-dog, I couldn’t help but think about… ketchup.

Now, I don’t know about you, but I’m not a fan of ketchup on my hotdogs (or burgers, for that matter). I always feel like the ingredient is super overpowering – that no matter what, a singular squirt of ketchup’ll then just make [whatever thing] taste like… ketchup. Fine enough when said ‘thing’ are French fries, or even some hashbrowns – but not what I want with my sandwich-like-objects.

That makes Ketchup an interesting ingredient, in a lot of way. While there’s certainly some variability to the dude’s writing, in my opinion the best thing Malcolm Gladwell’s ever written was this piece in the New Yorker, “The Ketchup Conundrum”. In it, he explores the question of why there’s a million mustards on the supermarket shelf, but basically only one ‘style’ of ketchup.

The TL;DR is that Ketchup is sort of a ‘complete’ flavor – it’s sweet, it’s sour, it’s umami:

What Heinz had done was come up with a condiment that pushed all five of these primal buttons. The taste of Heinz’s ketchup began at the tip of the tongue, where our receptors for sweet and salty first appear, moved along the sides, where sour notes seem the strongest, then hit the back of the tongue, for umami and bitter, in one long crescendo. How many things in the supermarket run the sensory spectrum like this?

Not sure where the ‘bitter’ comes into play re Ketchup, but I’m down for the thesis nonetheless.

The Central Thai dishes that’ve conquered the world, I think, have a similar thing going on – they’re often complete flavors.

Sweetness from - sometimes a fuck ton of - palm sugar. Umami and salinity from - sometimes a fuck ton of - fish sauce. Subtle bitterness from the herbs. Richness from the coconut milk. Sourness from lime or tamarind (though admittedly green curry doesn’t have a sour component).

These ‘complete flavors’ are… powerful. They’re great with rice. They’d probably be pretty great with French Fries, too. But the…

Xia-hot-dog rating? Not so great.

Better with hot dog than rice?: I mean, this specific dish doesn’t go super awesome with rice either in my opinion – I like it on a hot day next to some Khao Tom (thin rice porridge). But either way, it’s not really what I want on a hotdog.

Candidate #13: Sour-Spicy Shredded Potato (酸辣土豆丝)

Back to a Yunnan restaurant, I decided to go for suanla toudousi, sour-spicy shredded potato. A little bit of a risk, but I felt like texturally it might be nice on a hotdog for the same reason a coleslaw can be.

It’s alright. Kind of plain – there’s potential here, but I think it would work better as a component within a larger hotdog topping mix. Hunan Crispy Rice sandwich fillings, perhaps?

Xia-hot-dog rating: Alright.

Better with hot dog than rice?: Not by itself, not really. But in fairness, I suppose I usually like something else in addition this dish to go along with rice as well.

Candidate #14: Yunnan Braised Banana Flower (芭蕉花)

I know, I know. Indulge me.

It’s just… this Yunnan restaurant is run by a Wa woman, and they do some excellent renditions of dishes from the area. If you ever find yourself in the area and need to choose just one Yunnan restaurant, this is the one. Call ahead in the afternoon and get the leaf banquet if you can (though unfortunately the owners only speak Thai and Chinese).

Anyway, one of the things I love most from there is the Braised Banana blossoms, Bajiaohua. It’s fire with rice, so I just couldn’t help myself:

This obviously works, but it’s also not getting my blood moving.

Xia-hot-dog rating: Quite tasty

Better with hot dog than rice?: Not for me, no.

Candidate #15: Namphrik Ong (น้ำพริกอ่อง)

I needed to re-up on hotdog buns at this point, and unfortunately the buns I ordered from BigC (the Thai WalMart) were disappointingly stale. Went to my local American expat bar - who do a nice deep fried hotdog - in search of buns, and they were happy to provide. Was chit chatting a bit with the Thai owner about this silly project, and she immediately chimed in “what about Northern Thai Namphrik Ong? Tomato, ground meat, it would be like… a Chili Dog”.

Now, Namphrik Ong is usually more of a dip for vegetables than starch, but I’ve already broken my own rule-of-thumb a couple times already in this post. And it did sound good.

Given that the thing is a vegetable dip though, I decided to also toss in some cabbage and cucumber in as well.

Yeah. This way really really good. Maybe it was partly a function of me actually completing the hotdog with not just one topping, but this one shoots up to near the top of the list.

Xia-hot-dog rating: Fucking excellent.

Better with hot dog than rice?: I mean, again, Namphrik Ong isn’t really a xia-[starch] dish, so it’s hard to compare apples to apples. I would call the hotdogification ‘almost as good as the original context’.

Candidate #16: Som Tam, Papaya Salad (ส้มตำปูปลาร้า)

I actually had the deranged idea for topping a hotdog with Som Tam a long time ago, and performed a similar hotdog experiment at the aforementioned bar a few months into living in Bangkok. Unfortunately I can’t seem to find the pictures, if I actually took any (sometimes I need a break from documenting all of my eating).

I remember being surprised that Som Tam didn’t really work on a hotdog, but looking back I was using Som Tam Thai – a sweet, sour, spicy papaya salad most associated with central Thailand. If you have a Thai restaurant near you that has papaya salad, the probability is high that they’re whipping up this variant.

But there’s… an entire world of Som Tams out there. Going back to our discussion in Candidate #10, there’s one in particular called Som Tam Pu Bla Ra whose flavor leans on (1) that Bla Ra fermented fish sauce and (2) brined rice paddy crab. It’s savory, it’s funky, and if the issue with Som Tam Thai was ‘complete’ flavors like I was thinking before… it might just work.

Yep, this is pretty awesome.

Xia-hot-dog rating: Excellent

Better with hot dog than sticky rice?: Som Tam Pu Bla Ra is really, really good with sticky rice – I’m going to say ‘no’.

Winners, and how to make them

So… what’s better on a hotdog, Thai food or Chinese food?

Gun to my head, from my silly experiment… I’d say that Northern Thai food and Isaan food were the best, followed by Chinese food, followed by Central Thai. But there’s a lot of regional ground we haven’t covered here – particularly in China, but I mean, even in Thailand we haven’t even touched the East or the South. Still, a couple takeaways:

When adding Chinese food to a hotdog, be careful about the salinity of the dish. A lot of Chinese dishes are designed to xia-rice – something unseasoned – and so are a bit on the salty side.

When adding Thai food to a hotdog, be careful about ‘complete’ flavors – things which are sweet, sour, spicy, and umami. Or maybe we could just Occam’s Razor the whole thing – maybe it’s just that coconut milk and hotdogs simply don’t go great together? I’ll leave it up to you.

My personal favorites were: Northern Thai Tam Chili & Eggplant, Namphrik Ong, and Big Plate Chicken.

How to make Northern Thai Tam Chili & Eggplant and Nam Phrik Ong.

For these recipes, I’m just going to defer to this resource for Northern Thai cooking: Lanna Library, from Chiang Mai university.

It’s an awesome website – I can’t recommend it highly enough. It’s got both a Thai language version and an English language version, which get be useful for research. I’ve worked through a number of their recipes more or less verbatim, and they’ve come out excellent.

Here is their recipe for the Tam Chili & Eggplant.

And here is their recipe for Namphrik Num, the quite-similar thick salsa that I was also referring to in said section. I do think that Namphrik Num might be particularly good (as an aside, why the fuck don’t we top hotdogs with salsa actually?).

This is how they do Nam Phrik Ong – besides the shrimp paste, there’s nothing there that you couldn’t, like, find at a Krogers. And again, in the context of a hotdog, I would also recommend smushing in some cucumber and cabbage in there as well.

How to Make Big Plate Chicken

Way back when we had an old post covering how to make Big Plate chicken. It’s alright, definitely not the worst recipe out there on the internet, and even today I think it compares reasonably favorably to much of the front page of google if you search in English. But that was a time when I was really struggling to find legitimate sources on the dish… and luckily today there’s a lot more information out there.

Wang Gang’s recipe is solid and has English subtitles. Lao Fan Gu’s recent recipe is probably a touch better, but unfortunately has no English subtitles. And if you want to see a Uighur family actually making the dish, you can check this out (luckily, it seems that these guys are posting again on YouTube under a different account after – reading between the lines – a fallout with their MCN. The mind always has a habit of imagining the worst when it comes to Xinjiang, so good to see them back).

And of course, our recent Shanxi-style Big Plate Chicken probably wouldn’t be bad either.

That said, I also wanted to play around with the dish, see if I could alter the recipe slightly in order to make it more amenable to hotdogification. After all, just chopping up stuff from the braise works, but it’s a little klugey. I decided to see if I could smash together big plate chicken together with this something sort of like this Cantonese pork and mushroom dish (which might also be a reasonable candidate to xia-hotdog?).

Big Plate Chicken, hotdog-style

Important Note: this recipe was not tested. I made it once and scribbled down what I did. It was pretty good, but I might actually just prefer the klugey chopping up of the braise itself? You can use this as a jumping off point, but this recipe could definitely be improved.

Makes enough for like… three hotdogs?

In a heat proof bowl or pyrex, combine:

1 Star Anise

~ ⅓ of a Cinnamon stick

1 Tsaoko, Chinese Black Cardamom

1 Spicy Dried Chili Pepper

½ tsp whole Sichuan Peppercorn

1 cup hot, boiled water from the kettle

Cover, let sit as you’re prepping everything else.

Mince:

3 cloves garlic

~1cm ginger

the white parts from ~4 scallions

De-stem, de-seed, and dice into ~1 cm chunks:

50g medium chili, e.g. Chinese screw pepper or Italian long hots

Cut into 1 cm cubes:

100g potato

and rinse under cool water to remove a bit of the surface starch.

Dice into ~1 cm cubes:

225g chicken thigh

then marinate with:

¼ tsp salt

¼ tsp Sichuan pepper powder

¼ tsp chicken bouillon powder

⅛ tsp white pepper

½ tsp soy sauce

½ tsp Shaoxing wine

½ tbsp oil, to coat

In a wok, add

3 tbsp oil

and fry the potato pieces over a medium flame. Once the potatoes are translucent and just beginning to brown, shut off the flame, remove and reserve.

Evaluate your oil quantity. Add a little more oil, if needed, to get back to about the 3 tbsp mark. Then add:

15g rock sugar -or- ~2 tsp granulated sugar

Turn the flame to medium and fry the sugar until it dissolves and turns into a caramel, ~3 minutes. Then add the marinated chicken, up the flame to high, and fry for another 2-3 minutes until the chicken is good and colored.

Add the minced garlic, ginger, and scallion. Fry until fragrant, ~30 seconds. Swirl in

1 tbsp Shaoxing wine, baijiu, or beer

and swap the flame to low. Add in

½ tbsp red, fragrant chili powder, e.g. gochugaru

1 tsp Chinese 13 spice -or- 5 spice powder

½ tbsp Pixian Doubanjiang -or- Tomato Paste

and fry for ~1 minute until the oil is good and stained.

Strain in the infused spice water from above. Optionally toss in a couple of the spices if you’re feeling it. Season with:

¼ tsp salt

½ tsp chicken bouillon powder

And up the flame to high.

After ~7 minutes of boiling, add in the fried potato pieces and fry for another ~7 minutes.

At this time, a good hunk of the braising liquid should have reduced away, and the potatoes should just be starting to thicken the liquid. Season to taste, I added in another:

⅛ tsp salt

¼ tsp white pepper powder

¼ tsp MSG

⅛ tsp 13 spice powder (or 5 spice powder, of course)

Then add the fresh chili peppers and cook for another 30-60 seconds. The sauce should be relatively thick at this stage.

Add to hotdog, perhaps nestling in some cilantro, scallion greens, or raw minced garlic. Or maybe you can find a different mix:

Hot dogs, with the exception of Nathan's and Costco dogs, make me burp all day. I wish it were otherwise - but alas I've been cursed. The last time I had a hot dog was when I was taken in by a vendor in Munich selling curry wurst. I love sausages (I don't consider a hot dog in that category), so I ordered one. Hot dog with catsup and sprinkles of curry powder. Um, no thanks. I live most of the year in Mazatlán and they also try to confuse by calling them salchicha, which translates to 'sausage'. Hot dog; not sausage!

Saying all that, I commend you on your research and conclusions. Were I inclined to track down a Nathan's dog, there are several of your options I would be interested in trying!