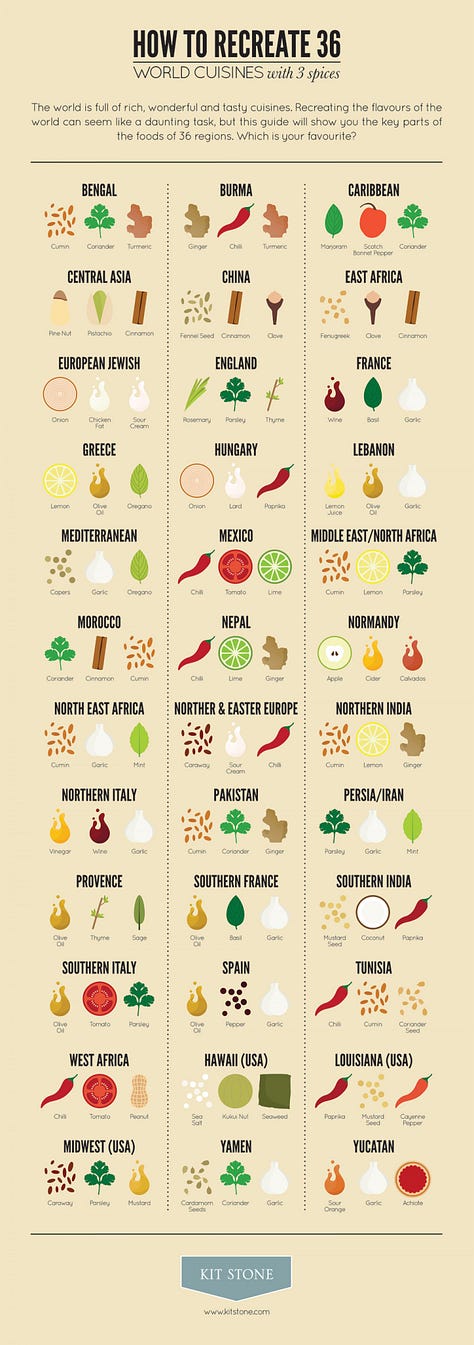

One of my biggest pet peeves has been the existence of those “international flavor profiles” infographics. For the uninitiated, this is the sort of thing I’m talking about:

Luckily, I feel like I see these graphics passed around a lot less than I used to (infographics likely had their time in the sun in the mid ‘10s), but you still see fundamental idea in a lot of cooking media.

“I was going for a ‘Chinese’ flavor, so I mixed together ginger, scallion, and soy sauce…”

Of course, when you’re actually in the kitchen, it’s obviously understandable to use those sorts of mental shortcuts – I’ve got certain flavor combinations in my head that are evocative of Central Thailand, of the Hunan province, of Korea, of Louisiana, etc etc. But it’s crucial to remember that they’re shortcuts.

Ginger/scallion/soy sauce is a quite common flavor profile within Chinese cooking, it’s a combination that works, and it can be employed outside of Chinese food to create a vibe of Chinese food… but it is not The Chinese Flavor.

Because… of course it isn’t, right? Even if we put aside the ridiculous culinary diversity China has to offer, any individual cuisine will use scores of different flavor profiles. Sichuan province is famed for their combination of Chili pepper and Sichuan pepper, but it’s not like Sichuanese are eating ‘numbing-spicy’ every dish for every meal. Sichuan professional cookery famously employs 24 flavor profiles, but even that’s likely significantly undercounting. Trying to distill the entirety of a cuisine into a handful of discrete “flavor profiles” is a bit like trying to flatten the totality of human behavior into 4-16 “personality types”. It’s just… too complex of a thing.

Case in point?

Above are a dish called Jingjie Banmian (荆芥拌面) - a homecooking classic from the Henan province. What you’re looking at are noodles topped with (1) stewed tomato and egg (2) garlic water and (3) jingjie, ‘lemon basil’, an herb quite local to Henan.

Tomato… garlic… basil…

If we consulted some of those above infographics, I’m sure they’d say that this combination would put us smack dab in the middle of Italy, not 8000km away in the North China plain.

This dish isn’t secretly Italian food cosplaying as Chinese, it wasn’t inspired by Pizza Hut. It’s a dish that squarely Henanese, and completely makes sense within a Henanese culinary context.

The Fundamentals of a Henan Basil Noodle

A look at the individual components will quickly dispel any notions of “Italianness”:

The Tomato.

The ‘tomato sauce’ here is in the form of stewed tomato and egg, a relatively common noodle topping in North China, that you can find everywhere from Xi’an to up to the Northeast.

It’s basically what it says on the tin – in place of the more ‘standard’ stir fried tomato and eggs, the tomatoes are simmered until they begin to break down, and then mixed with scrambled eggs.

The Basil.

In Henan, the ‘basil’ of this dish is called jingjie (荆芥). It was a bit confusing to track down, because in China at large that same jingjie (with the same Chinese characters) is a separate plant that’s employed in Traditional Chinese Medicine. Amusingly, that jingjie belongs to the same family as catnip, so sometimes you can find translations referring to the stuff as ‘catnip noodles’.

The actual, formal name for the plant in Chinese is Shumao Rou Luole (疏毛柔罗勒) - Ocimum basilicum var. pilosum. It’s – interestingly – an herb that’s quite local to Henan, even though it’s globally generally thought of as a tropical plant.

You will not be able to find Lemon Basil at a ‘general’ Chinese supermarket. I’ve heard that it’s sometimes available in-season at farmer’s markets in the west (although this might be the more lemon-y “Mrs Burns’ Lemon Basil”?). With a healthy hit of luck you might be able to find it at a Southeast Asian grocer – in Thai, the ingredient is called maenglak (แมงลัก) and in Indonesian it’s called kemangi.

The Garlic.

The garlic in this dish is fresh garlic, in the form of an ingredient often employed in Chinese mixed noodles called ‘garlic water’ (蒜水). If you’ve had Chongqing Xiaomian (重庆小面), you’ve had garlic water! The stuff is dead simple to make – it’s basically just minced or pounded garlic mixed with cool water and left to soak.

Henan Basil Noodles

Two notes before we get into it.

First, don’t stress if you can’t find lemon basil. We also gave this recipe a whirl using Thai basil, and – while different – it’s (obviously) also quite delicious. I’d imagine sweet basil would also taste good as well, but it’s a bit difficult for us to find over here in Asia. Use lemon basil if it’s around, use something else if it’s not.

Second, in the following recipe we make fresh noodles from scratch. The method employed is not particularly Henanese in execution, only in final result. It’s simply the way that Steph’s found is the quickest/easiest way for her to pump out noodles on a weekday.

You can also certainly use dried noodles too. They take a little more mixing, flavor is a little tougher to get ‘inside’, but… life is short and laziness is a virtue.

Ingredients

Makes two servings.

Dried Noodles, 200g, or…

To Make Fresh Noodles:

AP Flour (中筋面粉/普通面粉), 200g.

Salt, 2g.

Water, 90g.

For the Garlic Water:

Garlic, 3 cloves.

Salt, ¼ tsp

Water, 6 tbsp

Five Spice Powder (五香粉), ¼ tsp

MSG (味精) ¼ tsp

Soy sauce (生抽), 1 tsp

Dark Chinese Vinegar (陈醋/香醋), 1 tsp. Because this is tantalizingly close to a “western supermarket club” dish, you can use Balsamic vinegar (or a 1:1 mix of Balsamic vinegar and white vinegar) to substitute the dark Chinese vinegar if you don’t happen to have it on hand.

Toasted sesame oil (麻油), ½ tbsp.

For the Stewed Tomato and Eggs:

Tomatoes, 2 medium

Eggs, 2 medium

Seasoning for the eggs:

Salt, ⅛ tsp

White pepper, ⅛ tsp

Aromatics:

Garlic, 1 large clove. Minced.

Ginger, ~½ inch. Minced.

Oil for frying, ~2 tbsp

Liaojiu a.k.a. Shaoxing wine (料酒/绍酒), 1 tsp. Like the vinegar, feel free to sub this for sherry or brandy (or skip in a pinch).

Soy sauce (生抽), 1 tsp

Water, 1 cup

Slurry: Cornstarch (生粉/粟粉), ½ tsp; mixed with water, ½ tbsp

Final Seasoning:

Salt, ¼ tsp

MSG (味精), ¼ tsp

To serve:

Stewed Tomato and Eggs from Above. Or about one cup per serving bowl.

Garlic Water from Above. Or about 3 tbsp per serving bowl.

Toasted -or- roasted -or- fried peanuts, ~2 tbsp. Or about ~1 tbsp per serving bowl.

Cucumber, ~150g. Seeds removed and julienned. About one handful per serving bowl.

Lemon basil -or- your basil of choice, ~60g. Picked. If using Thai basil, perhaps rip the larger leaves in half. About one large handful per serving bowl, err on the side of generosity.

Process

For the Noodles, if making:

Note: after you boil the noodles, your shot clock is ticking. Do not let the noodles sit in the ice water for more than 5-10 minutes, else they will shred and break.

Mix the two grams salt in with the 200 grams of flour, then slowly drizzle that 90 grams of water in, combining with a chopstick. Once it forms rough shaggy bits, muster up all the force you have to press it into a ball. Rest for 45 minutes.

At this point, knead. As noodle doughs are quite dry, Steph finds this easiest to do using her feet (this is a technique sometimes employed in Japanese udon making). To do so, place the dough into a sturdy plastic bag, and step on it until it forms a rough sheet, ~30 seconds. Remove the dough, fold it in half lengthwise and in half again crosswise. Repeat this process eight times. Rest for 30 minutes.

Roll the dough out into a large rectangle, large enough it’s starting to exceed your work surface. Then take one side and begin to wrap it around your rolling pin, applying pressure to thin it out. Unroll, dust the dough in between wrappings, and wrap again. Once it’s reached a width of two millimeters, dust it again and fold it into layers to make it easier to cut. Slice into about one centimeter wide noodles.

To boil, add the noodles to a pot of boiling water. Allow the water to come up to a boil once again, then add in a half cup of cool water. Allow the water to come up to a boil once again, then remove the noodles.

Place in a bath of ice water (you could alternatively strain and rinse under cool water under the tap if you don’t feel like setting up the ice bath).

For the garlic water:

Add the garlic and salt into a mortar and pound into a paste. Transfer to a bowl, then add in the water, the five spice, the MSG, the soy sauce, and the vinegar. Mix well. Finish with the sesame oil, and let sit until you’re ready to serve.

For the Stewed Tomato and Eggs:

Core then dice the tomatoes into half inch chunks. Reserve.

In a separate bowl, crack two eggs, season with an eighth teaspoon each salt and white pepper. Whisk thoroughly, until foamy and no stray strands of egg white remain.

Mince a clove of garlic and a half inch of ginger, reserve.

To a hot wok (or whatever), add 2-3 tbsp of oil and give it a good swirl. With the flame on maximum, add the beaten eggs and allow to quickly puff and set. Pull the cooked bits to the side of the wok, letting the liquid pool and cook at the center. Once no more liquid is remaining, give the eggs a quick scramble and remove.

Same wok, no need to wash, add another ~1 tbsp of oil. Over a medium flame, fry the minced garlic and ginger until fragrant, ~30 seconds. Add the tomato chunks. Cook the tomato until it begins to break down, ~3 minutes. Swirl in a tablespoon of Shaoxing wine and mix, then swirl in a teaspoon of soy sauce and mix again. Add one cup of water, bring to a light boil, and cover with a loose lid.

Cook until the liquid has reduced by about one third, ~10 minutes.

Drizzle in a slurry of a half teaspoon starch mixed with a half tablespoon water. Once thickened to your liking, season with a quarter teaspoon each salt and MSG (or, to taste). Add back in the egg and mix well.

To serve:

Remove the seedy core from ~150g of cucumber, then julienne. Take ~60g of lemon basil (or your basil of choice), and pick it. If using Thai basil, perhaps tear some of the larger leaves in half.

Add the toppings to the cooked noodles, mix well.

The utility of tomato-egg-noodles is not to be understated, as an everyday meal by itself or as a base for variation. Thank you for posting this great recipe!