If you’re like a lot of people, you might’ve seen those Chinese noodle pullers and thought to yourself, “that seems cool. I kind of want to learn how to do that”. Then you go online, give it a quick google, and’re greeted an absolutely bewildering mix of discussion on the topic: everything from people that say it’s impossible to makes outside of China, to people playing around with adding nutritional yeast or L-cysteine to mix, to Buzzfeed videos claiming an easy foolproof version.

So with this post, I want to (1) try clear the air a bit, and clarify what a hand-pulled noodle actually is (2) teach you three different ‘hand-pulled noodles’, for three different skill levels and (3) teach a couple ways to actually enjoy them. It’s… a lot of ground to cover. This is a novella of a post, I know – I’ve actually had to put parts of it in the comments below because I hit reddit’s character limit (40k for a post, who knew?). Save it for later if you’re not in the reading mood. But I hope by the end of it all, you’ll understand – or at least appreciate - Chinese hand pulled noodles a little better.

What is a hand-pulled noodle?

So one of the things that makes it awkward to give a ‘recipe’ for hand-pulled noodles is that hand-pulled noodles aren’t really a ‘dish’ per se. They’re a technique. And to make things even more complicated, that English translation of ‘hand pulled’ really refers to two separate techniques: Lamian and Chenmian.

This distinction’s important. It’s why Babish tried and failed mightily at hand pulled noodles, while Inga Lam over at Buzzfeed seem to make them without a hitch – because Babish was trying to make Lamian (infamously difficult) and Lam was making Chenmian (common enough in home kitchens in China). Some other similarities/differences:

Now, both Lamian and Chenmian can come in different shapes. Likely the most classic version of both would be those spaghetti-looking sort, the kind that you’d probably immediately recognize as ‘noodles’. In this shape, Lamian is still called… Lamian. Easy enough. But perhaps confusingly, Chenmian in this shape can also be called Latiaozi (or, in some parts of the country, also Lamian… ugh).

But besides that, another common shape is wide-and-flat. If following the Lamian method, those flat sort are generally called kuanmian (宽面, literally ‘wide noodles’); if following the Chenmian method, they’re called… Biang Biang noodles.

Now, we’ve already covered Biang Biang noodles, but I’ll include them too because they make a great introductory pulled noodle. So the way I’ll organize this post is by going over:

Biang Biang Noodles. Wide-and-flat Chenmian that make for a great ‘my first pulled noodle’.

Chenmian, a.k.a. Latiaozi. Spaghetti-like Chenmian that’re slightly more involved than Biang Biang (they’re at slightly more risk to break, and are a touch tougher to get thin).

Lamian. Spaghetti-like alkaline noodles that are… a beast. The mount Everest of Chinese cooking.

Before we jump in with though, a quick word on flour.

What flour to use for pulled noodles?

Whenever we do any sort of dough related thing, we end up getting a lot of questions on the subject of “Chinese flour”. Is it bleached? Is it lower gluten? Etc. There seems to be this nagging misperception out there that flour here is somehow materially different than flour in the West.

In truth, there’s nothing overly different about Western flour and Chinese flour. That’s not to say that everything’s 100% the same – it’s just that that there’s an equally large difference between, say, King Arthur and Gold Metal as there is among those and Chinese brands.

As always, there’s a few different variables that’re important when picking out flour:

Gluten/Protein content. For this, we want a high gluten flour. Gives the noodle more bite. For Lamian you want a flour that’s more than 12% protein. For Chenmian, anything over 10% protein should work ok.

Age. Flour changes as it ages. Fresher flour is stretchier than older flour. In an ideal world, your flour would be less than 6 months old. Matters much more for Lamian than Chenmian (notice a trend?)

Fineness. The best flour for noodles and dumplings is quite finely milled, akin to an Italian 00 flour. Nice to have for Chenmian, but critical for Lamian.

For making Lamian, there’s actually a certain brand of flour most of the noodle shops tend to reach for called ‘塞北雪’ – this is what it looks like, if you’re curious. It’s 12.2% protein, usually used within a couple months of milling, and is extremely finely milled. But while that brand of flour is certainly a beaut to pull noodles with, extremely similar flours do exist in the West… in the form of Italian 00 flours.

So the TL;DR on flour is:

For Lamian, use an Italian 00 Pizza Flour. In the videos we used Caputo’s Chef Pizza Flour, which’s available online and popular among home pizza makers. It’s finely milled, pretty fresh, and is 13% protein. Works like a charm.

For Chenmian, 00 Pizza Flour is preferable but not required. All purpose flour is ok, just make sure that it’s not too low in protein. Our AP we usually use is 10.8% protein.

Wait, so for Biang Biang/Chenmian I can use AP Flour?

Yes, that’s right. But you’ll make your life much easier if you do an autolyse first. In both bread and noodle making, this will develop gluten and make for a stretchier end result (hey, just what we want in a pulled noodle!)

Dissolve your salt with your water, then combine the water with the flour bit by bit

Knead for ~1 minute until everything comes together

Cover with a plate, rest for 30 minutes

(note: in Western baking a ‘true’ autolyse is sans salt)

Biang Biang Noodles

So ‘Biang Biang noodles’ ring a bell, it’s for good reason. Ever hear of the restaurant Xi’an Famous Foods? Began in the basement of a Flushing mall… adored by pretty much everyone including the late Anthony Bourdain… blew up with 15 locations throughout New York… spawned countless copycats throughout the Anglophone world? Biang Biang is the main offering on their menu. It’s a noodle that’s… easy to love.

Now, that recipe we shared previously?. It’s a good recipe. A lot of people’ve enjoyed it. Feel free to continue using that one if you’re already used to it. But by learning a couple basic hand pulled noodle techniques, the process can become even easier, I feel.

Ingredients, Biang Biang Noodles:

00 Pizza Flour, preferably, -or- AP Flour (中筋面粉), 200g. If you do not use the 00 flour, do that autolyse beforehand.

Salt, ½ tsp.

Water, 100g. This dough is 50% hydration. Most pulled noodle doughs will be around that level.

Oil, 3 tbsp. For coating the dough during resting.

Techniques, Biang Biang noodles:

As befitting something with a grand total of four ingredients and made solely with your hands… pulled noodles are all about technique. Following a recipe for something like pulled noodles would be a little like reading a walkthrough for a game like DOTA 2. A great starting point no doubt, but somewhere along the way the onus falls on you to actually, like… get good.

For both this one and the following though, luckily that’s not going to be all that difficult. There’s just three techniques that you’ll need to know: hydrating, kneading, and pulling.

Technique #1: Cat Claw (猫抓手): A way to evenly hydrate your flour.

Streamable of the technique is here.

What you’re doing is adding water to flour bit by bit, then rubbing the flour between your thumb and the back of your fingers. What you’re looking for is a final result called ‘suizi’ (i.e. ‘wheat grains’), which looks something like this.

The reason evenly hydrating the flour is so important is because we don’t want to add too much water to the dough. This is also one of the reasons why finely 00 milled flour can be so helpful – simply by how well the stuff hydrates.

Like, add 50 grams of water to 100 grams of AP Flour. Do a rough mix with a chopstick, and you’ll get something like this. Compare that against those ‘suizi’ from above, which was made with some finely milled 00 with the same amount of water. If you’re anything like me, you might look at the first picture and think to yourself, ‘damn, needs more water!’ But it doesn’t need more water – it just needs to be hydrated better.

Cat claw + autolyse is a powerful way to make even the most ‘meh’ of AP flours the hydrate like they should.

Technique #2: Making the Abacus String (算盘子): Kneading and aligning the gluten into one long rope.

Here’s an imgur album detailing the process step-by-step. I know it looks like a lot – it’s not that bad, I promise.

Basically, you’re just kneading this stuff by repeatedly curling the dough into itself until you get one long log. Then you fold it in half, punch it down, and start curling again. It’s not necessarily any harder that the standard kneading motion for bread, just different.

We’re doing this because we not only want to develop the gluten network in the dough, but also align the gluten strands. The idea’s somewhat similar to the slap-and-fold technique in Western bread-making, albeit with a different goal in mind. The slap-and-fold gets the gluten into a sort of criss-cross pattern, while here we’re aiming for one long rope.

When we go over Lamian below, this process becomes both insanely important and incredibly tedious. Luckily, for both Biang Biang and Chenmian, you just need to do this for ~8 minutes or until the dough gets smooth.

Technique #3: Biang-ing and Ripping the Noodle:

This noodle gets its name from the characteristic sound it makes as it smacks the table. Far too few food names are onomatopoeias.

Streamable of the technique is here.

Basically, what you’re going to be doing when pulling is first rolling it out into a ~10 inch to ~2.5 inch sheet. Then, you’ll make a small indentation in the noodle with a chopstick – this will be your ‘ripping point’. Next you grab the noodle, smack it ~10 or so times against the table while pulling gently to lengthen it out.

The way you hold the noodle while pulling/smacking is quite important, however. If you pinch the dough at all, it can end up breaking. What you want to do is lay the noodle over your four fingers, and simply using with your thumbs to hold it in place- force shouldn’t really be applied. Here’s a picture of what your hands should look like.

Once the noodles are about arms length, rip it in half at the indentation that you made your chopstick. We usually rip one end like we did in the above video, but you could rip both ends, or you could keep it in one big ‘loop’. Up to you.

Process, Biang Biang Noodles:

Mix the salt with the ice water, then add water by ‘cat clawing’ the mixture into the dough. Press and knead for ~1 minute into a rough ball. Refer to the ‘cat claw’ technique for detailed instructions. Once all the moisture’s absorbed into the dough, knead it real quick (as normal, like you usually would bread and such) to get it into a ball.

If using AP flour instead of 00 flour, cover and let rest for ~30 minutes.

Move the dough to a work surface, knead using the ‘making the abacus string technique; 8-10 minutes. Refer to the ‘making the abacus string’ technique for more information. What you’re looking for is the dough to have a smooth surface on both sides like this.

Fold the dough length-wise twice; smack it into a rectangular box, toss in a bowl and rest for ~10 minutes. From the previous step, you will have one long ‘rope’ of abacus string. Punch it flat. Fold it in half lengthwise twice to shorten it right up. Then smack it into a rectangle – it’s a bit tough to describe, so I’m going to cheat with a streamable.

Roll the dough out into roughly a ~7x4 inch sheet. No need to obsess over the exact measurements here, but that’s the size that we were working with.

Cut the dough into four long strips. So each strip would be roughly ~1x7 inches.

Thoroughly oil a plate, toss on the dough strips, then oil them. Cover with plastic wrap in such a way that the plastic wrap is clinging to the strips themselves. Remember – we usually use a few tablespoons worth of oil here for this step, so don’t be shy there. When you’re covering with plastic wrap, have the wrap cling to the noodles, to minimize air in the plate. That said, don’t go nuts - we’re not vacuum sealing.

Rest the dough strips for at least 3 hours and up to 8 (or overnight if need be). We find 4 hours to be about ideal for resting. Going up to 8 is fine too – 24 hours is perfectly workable as well, but after that the dough will likely become a bit too soft and pull-y.

Remove a strip, patting slightly with a paper towel if overly oily. Roll it out into a ~2.5 to ~10 inch long sheet. Exact size here’s nothing to obsess over, just what we find ourselves working with.

Biang the Noodle: Press down the middle of the noodle with a chopstick. Refer to the ‘Biang-ing the Noodle’ technique for more details. The indentation in the noodle should look something like this. After we slap the noodle longer, that indentation will be where we tear it open (to get an even longer noodle).

Biang the Noodle: Hold the noodle in your palm, lightly pressing with your thumb. Smack the noodle down against your work surface around ~ten times to lengthen the noodle. Refer to the ‘Biang-ing the Noodle’ technique above for more details. You’re looking for something about a meter long, like this.

Biang the Noodle: In the center of the noodle, push through the groove that you made with the chopstick and pull apart the noodle to get something even… longer. We break one end of it. Tearing apart will look something like this – again, some people break both ends, and some keep the circular shape.

Boil for ~1 minute until it floats. Work through your other noodles as each is boiling.

Chenmian

So Chenmian are also referred to as Latiaozi, and – interestingly – in Xinjiang as ‘Laghman’. They’re basically going to be almost identical to our Biang Biang noodles from above, albeit in that long/round spaghetti-like shape.

So, this recipe is going to share a lot with the previous recipe. So I’m going to cheat and refer to the above recipe a bit. If you’re just perusing this post out of curiosity, the substantive differences are the “technique #3: pulling” and the process starting from step #6.

Ingredients, Chenmian:

Same as the Biang Biang above.

Technique #1: Cat Claw (猫抓手)

Again, Streamable of the technique is here.

Technique #2: Making the Abacus String (算盘子)

Here’s that imgur album detailing the process step-by-step again.

Remember, you’re just kneading this stuff by repeatedly curling the dough into itself until you get one long log. Then you fold it in half, punch it down, and start curling again.

Technique #3: Pulling the Noodles

Streamable of the technique is here.

Overall, the pulling technique for this noodle’s pretty self-explanatory. What you’ll do it roll it out a touch by hand (until it’s, say, ~6 inches long), then pull it. Once you can start to feel the resistance in the noodle, stop. Then continue to thin/lengthen the noodle by repeatedly smacking it against the table, ala the Biang Biang noodles.

Note that there will be a limit as to how thin you can get the thing. What you’re looking for is something a touch thicker than fresh spaghetti, or about the same thickness as Japanese ramen. If you’re staring at a noodle that’s still a little too thick, you’ve got two options. First, you can fold the noodle in half and continue to smack in against the table. This’ll help things get a bit thinner, but you do have to be careful – it’s very easy for the noodle to break when folded. Second, you’re still working with a stubborn noodle, you can leave it there and let it rest as you work through the remainder – picking up again after five minutes or so, you can generally get it a bit thinner.

Process, Chenmian:

Video of making Chenmian is here if you’d like a visual.

Mix the salt with the ice water, then add water by ‘cat clawing’ the mixture into the dough. Press and knead for ~1 minute into a rough ball. Once all the moisture’s absorbed into the dough, knead it real quick to get it into a craggily ball.

If using AP flour instead of 00 flour, cover and let rest for ~30 minutes.

Move the dough to a work surface, knead using the ‘making the abacus string technique; 8-10 minutes. Refer to the ‘making the abacus string’ technique. What you’re looking for is the dough to have a smooth surface on both sides like this.

Fold the dough length-wise twice; smack it into a rectangular ‘box’, toss in a bowl and rest for ~10 minutes. From the previous step, you will have one long ‘rope’ of abacus string. Punch it flat with your fists. Fold it in half lengthwise twice to shorten it right up. Then sort of smack it into a rectangle – streamable is here, again.

Roll the dough out into roughly a 4x7 inch sheet. No need to obsess over the exact measurements here.

Cut the sheet in half, but be sure to pay attention to which side the long side was, as that’s the direction that we’ll be cutting. Cutting this sheet in half is actually optional, but especially if you’re just getting started out I’ll be easier to work with shorter noodles.

Cut into 1cm strips. Or roughly 12 strips per half-sheet, for 24 noodles total.

Thoroughly oil a plate, toss on the dough strips, then oil them. Cover with plastic wrap in such a way that the plastic wrap is clinging to the strips themselves. Don’t be shy with the oil. Also, when you’re covering with plastic wrap, have the wrap cling to the noodles, to minimize air in the plate – something like this is perfect.

Rest for 3-8 hours, or up to 24. To relax the gluten. Again, 3 hours is the minimum here, we generally like it at around the 4 hour mark.

Remove a noodle, slightly pat off some oil with a paper towel if needed. Sometimes it can get a bit too oily to work with.

Pull the noodles. Pull the noodle according to technique #3 above – remember not to get too greedy re thinness!

Boil the noodles until a touch past al dente, ~45 seconds, then shock under running water.

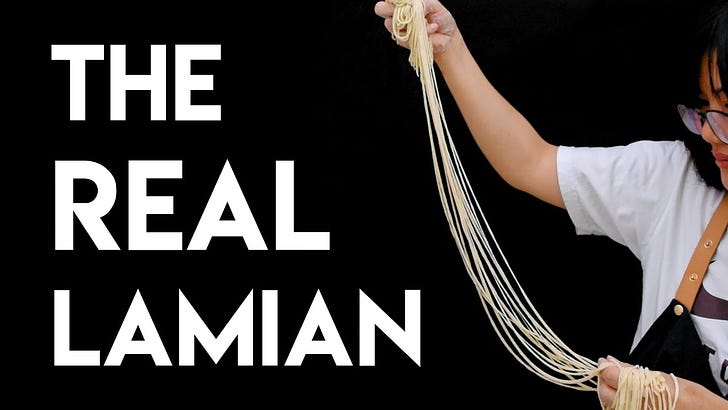

Lamian

Abandon all hope, ye who enters this recipe.

Before we do anything, let me pass on you the advice one dude at my local Lanzhou Lamian shop gave me a number of years back when I was badgering him for tips on Lamian technique: “Give up. Do not try. You’ll never know how to make Lamian.”

At the time, I took it as a sort of ‘oh you’re just a foreigner, you’ll never understand’ kind of thing (the closest thing a white dude in China can get to a microaggression lol). Now, I understand the wisdom in his words. I wish we’d listened.

This is by far the hardest recipe we’ve ever done on our channel. It’s so tough that it makes Har Gow look like a relaxed weeknight dish. The only thing I can think of that can even come close to it is the proper sourdough-starter smiling Char Siu Bao, and that’s a recipe where commenters reporting failures outnumber commenters reporting successes about 10:1.

So just… stop. Turn back. It’s not worth it. Scroll right on past this, move on with your life. You’ve got the above recipes for Chenmian, right? Those are fun. You can impress all your friends with those. It’s good enough for most people – an untelling eye probably couldn’t even tell the difference.

Making Lamian, you will fail your first time. And probably your second. And probably many times after that. But if you keep at it… one day, things’ll click for you. And you can be content in the knowledge that you’ll be one bad-ass noodle maker.

Why is Lamian so hard?

So like, Chenmian wasn’t too bad. Pretty much any intermediate home cook can make Biang Biang noodles. And while the thinner spaghetti-like sort might have a couple more moving pieces, in the grand scheme of things they’re not so bad, either.

What makes Lamian so difficult is the introduction of alkaline.

For those of you out there that don’t live and breathe the world of Asian noodles, alkaline noodles have this fabulous bite to them. In the mainland this texture’s referred to as ‘tanya’ (弹牙), though perhaps you might’ve heard it called by the Taiwan term ‘QQ’. You could think of it sort of like… al dente. What makes alkaline noodles so beautiful is that they retain that sort of ‘al dente’ texture, even after being fully cooked. Alkaline is what makes Japanese Ramen, Japanese Ramen; it’s what makes Cantonese Wonton Noodles, Cantonese Wonton Noodles.

And in my personal opinion, alkaline ends up being increasingly important as the noodle itself gets thinner. Super thin noodles can easily end up much too soft if you’re not careful – while I don’t think Angel Hair pasta quite deserves its bad reputation, I do believe that it would be a much better product if they added alkaline to the mix.

Now, for most alkaline noodles the process isn’t all that hard. You add a bit of sodium carbonate to the dough (or a solution of sodium carbonate/potassium carbonate called Kan Sui/Jianshui), and continue along your merry way… rolling things out thin and either cutting them with a knife of a pasta maker.

Making an alkaline noodle that can pull? Alkaline stiffens dough! It’s like… a counter-intuitive proposition. Would almost feel like magic. And unfortunately for everyone trying to replicate this stuff outside of China? It kind of is magic – or at least, uses a magic ingredient. That is… Penghui.

Penghui

Let’s get something out of the way at first. Go on Amazon. Search “Penghui”. Find anything?

At least sitting here in the Spring of 2020, I can’t find jack. The only way to find Penghui is by ordering industrial quantities from Alibaba or through specialty middlemen (e.g. a place like ChinaHao).

See, penghui, traditionally, is the ash of a specific soda plant called ‘Penghuicao’, or Halogeton Arachnoidius in English. The old school way of making the stuff would be to burn the plant, then when it’s at a specific temperature to splash water in it. Apparently, it then forms a rock like this. I’m not sure how any of that makes sense (ash + water = rock? someone help me here…), but then to use the penghui… you’d chip some of that off, mix it with water, then apply it to your noodles.

Now, like the ash of many other soda plants, traditional Penghui was undeniably alkaline - probably from either potash or sodium carbonate. But besides that, it must’ve had something else in the mix, something that helped the noodles pull. While I can’t seem to find any information on the chemical composition of traditional penghui (feels like a fun thesis for any anthropology grad students out there lol), luckily for us… it actually doesn’t really matter. Because basically no one’s using that old school Penghuicao ash these days, either.

Whether for economic or food safety reasons (depends on who you ask), in 1989 food science researchers from the Lanzhou University in Gansu developed a mix of additives that could be used in place of the traditional Penghui. And while it’s a matter of debate as to whether the explosion of hand pulled noodle shops in China over the last few decades is because of that innovation, it’s undeniably true that the spread of Lamian noodle joints and manufactured Penghui happened in tandem. Sometimes I joke that all those noodle shops around the country are really just a massive Penghui sales operation – a joke with a shred of truth to it, because if you peek back into the kitchens at Lamian shops, you’re almost guaranteed to be greeted with the same blue bag at each one.

What’s in that blue bag? Well, I’m glad you asked. It’s:

50% sodium chloride (salt)

45% sodium carbonate. Can be produced at home by baking baking soda in an oven for ~1 hour at 150C.

4% sodium triphosphate, a.k.a. STPP. An emulsifier that’s totally available in the West – actually, often it’s used in American supermarkets in order to make fish/shrimp retain more water (looks more plump, while also allowing them to sell you more water and less seafood). Here, the sodium triphosphate acts as a dough strengthener, making the dough less likely to break when you pull it.

1% sodium metabisulfite. A reducer which is used as a preservative in winemaking, and also totally available in the West. The function here is to help relax the dough, making it easier to pull.

Now, given that all of these components are available in the West, the question of whether we could just mix all this shit together naturally follows. And the answer is… kind of.

In the linked video, I try my hardest to make my own ‘homemade Penghui’ using those component parts. The problem is that we totally use about two grams of Penghui in one batch of noodles, so that means one 200 gram serving of noodles uses something like 0.02g of sodium metabisulfite and 0.08g of STPP. With those kinds of quantities, accurate mixing of the powders become absolutely imperative (you can’t make a solution either, as sodium metabisulfite quickly oxidizes when in contact with water). So without an industrial screw mixer, it’s really easy to, say, have some batches have a bit too much reducer… and some have not quite enough.

But does it work? Sorta. By taking every precaution I could think of making the homemade Penghui, we were able to pull it to a roughly spaghetti-thin noodle, but no thinner.

I would recommend the homemade Penghui to experienced noodle pullers abroad as a stopgap between Penghui shipments. I would not recommend the homemade Penghui to a beginner. When learning, when you confront a batch of failed noodles you want to be sure that it’s your technique that’s the problem, and not your Penghui. So if you’re actually serious about learning Lamian, go on ChinaHao (or a similar website), bite the bullet and just… drop the $70 and buy too much Penghui.

Ingredients, Lamian:

Pizza Flour -or- Chinese Lamian Flour, 250g. The finely milled flour for this one is non-negotiable. Again, for standardization purposes, we used Caputo’s Chef Pizza Flour.

Ice Water, 120g. So traditionally in the Northwest they use ice water in summer and tap water in the winter. The basic idea is that the ideal Lamian kneading temperature is around 28C, but shouldn’t really exceed 30. Why that is I can really find a compelling answer for, but the advice seems to ring true from experience. Of course, most of our kitchens are temperature controlled these days, so we would personally opt to use ice water all year long.

Salt, ½ tsp. 2 grams. To be mixed with the ice water.

Any dense oil, e.g. Olive oil, ~3 tbsp. Dense oils seem to ‘cling’ better to the dough while working it. We used Sichuan Caiziyou (virgin rapeseed oil), but olive oil also worked well in our tests. While working the dough you’re going to be constantly oiling your hands and the dough to make sure things don’t dry out. I’m giving an amount because it’s certainly true that some of the oil ends up in the dough itself. It’s approximate because it changed from batch to batch for us – we found that it ended up ranging between two and four tablespoons.

Penghui (蓬灰/拉面剂), 2g; to be mixed with 10g of water. Again, if first starting out, I’d strongly advise biting the bullet and just figuring a way to source some Penghui. If you would like to try a homemade Penghui, this is how I did it. In a mortar, I pounded 100g of salt until powdery (super annoying), then did a quick pound of 90g of sodium carbonate, 8g STPP, and 2.5g (3/4 tsp) sodium metabisulfite. Be careful with the sodium metabisulfite – while this minuscule amount is probably ok, it would be more responsible for me to advise using PPE and/or going outside when using it. It’s not overly toxic or anything, but do not smell it as if it’s inhaled directly it can temporarily make you unable to breathe for a spell. Then I passed that through a fine mesh sieve a couple times, then mixed in a stand mixer with the paddle attachment on speed three for 30 minutes to combine. In hindsight it might have been a good idea to bake my salt first to ensure that there’s not excess moisture there. But regardless, store your mixture with food safe dessicants (i.e. those little silica gel packs that help absorb moisture).

Techniques, Lamian:

Ok, so I usually like giving these ‘high level overviews’ of what’s generally going on before I dive into the weeds. But if I try to give a high level overview here, you’ll think I’m speaking a different language:

Cat claw the water into the flour

Knead using the making the abacus string method

Apply the penghui by either the three-fold-two-wrap method or the abacus string method

Comb the gluten

Test for pullability

Pull

Feels almost easy when I put it that way lol. Some of these techniques are the same as what we went over before, but (1) the abacus string method will be more involved and (2)

Technique #1: Cat Claw (猫抓手)

Streamable of the technique is here.

Same Cat Claw technique as above, nothing overly special going on. Just hydrate that sucker.

Technique #2: Making the Abacus String (算盘子)

Ok, so this is probably the most complicated move on the list – it’s similar to what we covered above, only you’ll need to be a bit more paranoid throughout the process. Here’s the imgur album detailing it step-by-step.

Just like the above noodles, the basic idea is that you’re kneading it by continuously curling the dough. You get a long log of curled dough, then flatten the sucker out, then repeat. Getting the dough flat enough to be repeatedly curled up takes a bit of technique though. While you could theoretically crack that nut however you wanted (a pasta maker is one possible – but not necessarily easier - route), the common move is to (1) punch the dough down then (2) press it flat further by crossing your hands and smushing down the edges (3) repeating the hand cross flattening with your hands crossed in the other direction to make things totally even and flat.

This is the most important step in the entire process. At some Lamian schools, the final test is to make an entire batch of Lamian from start to finish in less than 20 minutes flat. Of those 20 minutes, this step right here takes about 15-18 minutes.

You’ll know you’re ready to move onto the next step when it can form a smooth hole if you tear it. I like this visual right here. This was a batch of Lamian dough that was almost ready. The hole on the right is smooth, the hole on the left is jagged. You want the hole to look like the one on the right.

This might take you a long time to do it. The saying in Lamian making is that you need to do this “9 times 9 times” (i.e. 81 times). That’s ultimately just a saying though, because the number ‘nine’ sounds a lot like ‘a long time’ in Mandarin. But we’ve counted before. We tend to need 30-40 times of repeating this process to get to the point we need. This takes us about a half hour of kneading, but it’s very normal to knead for 40 or even 50 minutes when you’re just starting out.

Technique #3: Three folds, two wraps (三叠两包): Evenly apply your Penghui

When we add the Penghui, we’ll mix it with water first, then apply it bit by bit into the dough.

Streamable of the technique is here.

Basically, when you add the Penghui, it’s pretty important that it evenly gets incorporated into the dough. You don’t want bits of your Penghui water ‘spilling’ out of the though, so the three-folds-two wraps method helps keep all that inside.

Don’t feel like learning yet another technique? No problem. You can also just continue to use the abacus string method from before – applying the Penghui when the dough is flat. You’ll just need to be good about only adding a bit of Penghui to the dough at a time.

Technique #4: Combing the Gluten/Testing for Pullability (拉条顺筋)

So, there’s two ways to do this step. This is a clip of the classic ‘twisting’ approach done in Lamian noodle shops, but let’s just set that one aside for now. We feel like it’s easier to use the following method of gluten combing, which also helps give a nice ‘test’ of sorts for pullability.

Streamable of the technique is here.

Basically, what we’re doing is repeatedly pulling and folding the dough over itself, slapping it against the table between each pull. This’ll not only help strengthen the gluten network, but it’ll also help give us a ‘test of sorts’ to ensure that the dough is ready for pulling. If you can pull and fold it over itself at least five times without breaking (six is ideal), you are ready to move onto the next step.

But what if it’s not quite there? Well, now’s the point where you need to trust your hands and your instincts, and veer off-recipe. You’ll need more Penghui and more time kneading. Mix another batch of Penghui water, but maybe only add, say, a fifth of it at first. Use the abacus string method, knead it for a few more minutes. Then try to gluten comb again.

Note that for this step, you need to make sure everything is super oily. Your hands, the table, your dough, everything.

Technique #5: Pulling (拉面)

Ok, so I want you to get your expectations straight here.

You might have visions in your head about wildly pulling these noodles and putting on a show for everyone. You are not a Lamian master: do not try to do this. Your Lamian will become uneven and break.

This is a game of applying force evenly. It is not easy. It is entirely possible that you will do everything up to this step perfectly, but screw up here – getting some noodles that look thinner than angel hair, and some that wouldn’t be out of place in a Biang Biang.

Work slowly and deliberately. If you fuck up, you fuck up – no shame there. But don’t fuck up because you were overconfident. The noodle cares not for your ego.

Streamable of the pulling is here.

Notice that we’ll be adding some flour on the table for this step. Each time you pull, toss the center of the noodle in your little ‘flour mountain’ as you do it.

You’ll need five pulls to get to a ‘normal thin’ Lamian. That’s be about the same size as spaghetti – those can either be good in soup or stir-fried. Six pulls gets you to a ‘whisker thin’ Lamian, which’s usually what’s served in the Lanzhou beef noodle soup. Seven pulls gets you to ‘dragon beard’ thin Lamian… which’s thin enough to thread a needle, is completely insane, and way beyond our skill level.

Process, Lamian:

Ok, got all that? Remember, high level overview:

Cat claw the water into the flour

Knead using the making the abacus string method

Apply the penghui by either the three-fold-two-wrap method or the abacus string method

Comb the gluten

Test for pullability

Pull

As always, there’s a video too if you’d like a visual.

Mix the salt with the ice water, then cat claw the mixture into the dough. Refer to the cat claw technique for details.

Knead everything into a ball, ~1 minute, then cover and rest for 30 minutes. At the Lamian shops they’ll generally move straight on to the next step here, but we find that kneading’s a bit less painless with a quick rest.

After 30 minutes, remove the dough and roll it out into ~1.5 ft log. Thoroughly rub your hands and work surface with oil. Again, make sure that everything is good and well oiled though this entire process. Rub your hands and work surface obsessively.

Punch down to flatten the dough. Then continue the making the abacus string method for ~30-40 minutes. Refer to the ‘making the abacus string’ technique for detailed instructions. And remember: 30-40 minutes is an estimate. The timing will depend on your skill in doing this. It would be almost unheard of to do this in less than 15 minutes. I’d guess that it’ll take 40 minutes for a beginner. The dough will be finished once (1) small bubbles begin to form as you’re flattening it and (2) it forms a smooth hole when torn.

Combine the two grams of Penghui with ten grams of water. Make sure it’s completely dissolved.

Flatten the dough ala the abacus string technique, then wet your hands with the Penghui water and apply it to the top of the dough. Then follow the three-folds-two-wraps technique outlined above. Refer to the three-folds-two-wraps technique for detailed instructions. To reiterate, you can also just continue to use the abacus string technique here if you prefer – simply add the Penghui a bit more conservatively.

Fold the dough in half, roll it into about a foot and a half log, then liberally apply oil to your dough, hands, and table. A well oiled situation is important for the gluten combing.

Comb your gluten. Refer to the gluten combing technique for more information. If you can fold the dough over itself 5-6 times without breaking, you are ready to move onto the next step. If you can’t, go back to step five but add only a fifth of the Penghui water, and knead using the abacus string method for another ~5 minutes. Loop through these until you’re at the correct consistency.

Flour your work surface, pull the noodles. Pull according to the pulling technique outlined in technique #5 above. Remember, work slowly and deliberately. We'd recommend five pulls for fried noodles, six pulls for soup noodles. Tear off the very end of the dough – that bit’ll be garbage, unless you got a better idea.

Immediately toss in some boiling water to cook. Until just past al dente, ~45 seconds. If not eating immediately, you can flour them up… but try to devour sooner or later.

How to use these noodles

Ok, so great. You’ve got some noodles. How to actually make use of them?

While I’m probably blanking on some stuff, there’s three basic ‘categories’ of dishes you can make with these guys: (1) soup noodles (2) mixed noodles and (3) fried noodles. You can make pretty much any these three things with any of these three noodles (with the possible exception of fried Biang Biang noodles… but then again I’ve heard Xi’an Famous Food’s famed Cumin Lamb Biang Biang is actually fried?)

So because I’m starting to run out of breath here, I’ll choose one dish from each ‘category’ so you can at least get an idea.

Soup Noodle: Lanzhou Beef Noodle Soup:

If I were a better recipe writer, I’d follow up the Lamian recipe with an equally long and involved recipe for the beef soup that’s traditionally eaten with it. And listen, it’s a good soup. But after all the blood, sweat, and tears of testing La Mian, we… didn’t feel like researching and testing the soup.

So I’m going to cheat, I guess. Here’s a recipe for Lanzhou Beef Soup, courtesy of the blog ChinaSichuanFood. Elaine’s stuff’s excellent as a rule of thumb, and in her recipe she was… smarter than us and just used packaged Lamian haha (not the same thing, but… is 100x the pain worth 3x the deliciousness?). While we might have some of our own opinions here or there (e.g. the chili oil used up in the Northwest is usually made with a milder chili closely related to Kashmiri), her recipe is great and the broad strokes of it would also be how we’d approach it.

If you’d like, you can also use Elaine’s recipe for the soup together with the Chenmian. While the very best Lanzhou beef soups would probably opt for something thinner than the chenmian (i.e. the six-pull Lamian), it would still be very delicious.

Mixed Noodle: Youpomian (油泼面)

For Chenmian or Lamian, (if served unfried or without soup) it’s probably most common to see them with a saucy stir fry topping called gaizhaomian. One example would be something like this. We have no recipes for that kind of thing off the top of my head (apologies), but could give you an educated guess if you were curious and pressed us.

For Biang Biang, probably the most classic 'mixed' topping is a chili oil based sort called Youpo Mian. But there’s tons of other toppings use for Biang Biang, some of which I covered in a separate Biang Biang noodle topping post. For the sake of brevity though, let’s just cover the chili oil one.

Ingredients, Chili Oil Topping:

Leek (大葱), ~3 inch section. Minced.

Garlic, 2 large cloves. Minced.

Chili flakes (辣椒粉), 4 tsp. In the Northwest, they actually use a slightly milder chili for their chili oil. It’s closely related to Kashmiri chili, so making some chili flakes out of kashmiri chilis would have a pretty authentic flavor to it. That said, we used the bog standard Chinese chili flake, and you could also use the red pepper flakes y’all get in the West. Korean chilis might also be a solid direction here.

Sichuan peppercorn powder (花椒面), ½ tsp, optional. You could go either way for this one.

Light soy sauce (生抽), 4 tbsp.

Dark Chinese vinegar (陈醋/香醋), 1 tbsp. If you’re rolling through this recipe and this is the only thing you can’t source… eh… hmm… I dunno, use half cider vinegar and half balsamic. I just made that substitution up on the top of my head though so please don’t hold me to that. Or maybe just buy some, it’s a good ingredient.

Salt, ¼ tsp.

Peanut oil (花生油), 5 tbsp. To be heated up and poured over the chili flakes/garlic. A sizable quantity of oil’s important here to keep things slippery.

Baby bok choy (上海青), ½ or 1, quartered. Optional, use whatever blanched green or vegetable you want. Bean sprouts are also hyper common.

Process, Chili oil topping:

Mince up the leek and the garlic.

While you’re cooking the noodles, toss the quartered bok choy in with it to blanch. Blanch for 45 seconds.

Nestle the vegetable in and put all the non-liquid toppings over the noodles. Spoon the soy sauce and the vinegar around the sides.

Heat the oil up until it’s just starting to smoke, ~215C, then pour it over the noodles, aiming for the chili and the garlic.

Fried Noodle: Chaolamian (炒拉面)

This fried noodle can be made with both Chenmian and Lamian (I doubt Biang Biang would work, but hey – if you wanna be experimental). There’s many types of fried pulled noodles of course – this is a classic version that you can find at noodle shops with a tomato/chili bean paste base.

Ingredients, Chaolamian:

For this specific recipe, we opted to use egg as the protein, but that’s basically just because we had some on hand. You could alternatively use lamb, marinated beef… or really whatever.

Noodles, 300g. Chenmian or Lamian are both great. If you want to give this one a whirl without making hand pulled noodles from scratch, feel free to try this with… whatever noodle you feel like. Japanese Ramen (the proper sort, not Top Ramen), Sichuan alkaline noodles, longevity noodles, etc etc.

Eggs, 2. To be beaten and scrambled. Or, your protein of choice.

Garlic, 3 cloves. Crushed.

Tomato paste (番茄酱), ½ tbsp. A real thing in Northwest cooking, I swear.

Sichuan Chili Bean Paste (红油郫县豆瓣酱), ½ tbsp. Something I’ve learned recently – most chili bean pastes that I’ve worked with here in China are actually a sub-category of chili bean paste called ‘chili bean paste in red oil’. No wonder some people’ve had problems with chili bean paste-based recipes. Sigh. You’re looking for the sort that comes in a big red plastic jar, like this. It’s also available (super overpriced) online.

Baby bok choy (上海青), 100g. Sliced horizontally. Or, your veg of choice.

Light soy sauce (生抽), 1 tbsp. For seasoning/use while stir-frying.

Seasoning: ½ tsp salt, ¼ tsp five spice powder (五香粉), ½ tbsp of dark Chinese vinegar (香醋/陈醋). One of the few stir-fries that we’ll season with five spice powder directly. For the dark Chinese vinegar, there’s two big varieties in China – Chinkiang (镇江香醋) and Shanxi Mature Vinegar (山西陈醋). Both are ok here, though Shanxi Mature would be slightly preferred (we used Chinkiang). If working with Western vinegars, our suggestion would be subbing it with a ratio of 2:2:1 balsalmic:white vinegar:water.

Other vegetables for the stir-fry: Red onion (洋葱), ¼ quarter; Green mild chili (青椒), ½; Red mild chili (红椒). All sliced. For if you don’t feel like grabbing different color chilis you can also just use solely green or red mild chilis. Anaheims are perfect, poblanos would be a little spicy but still work. Bell pepper would also be acceptable. Red onion is for looks, yellow onion is also totally cool.

Toasted sesame oil (麻油), 1 tsp. For finishing.

You’ll also need ~2-3 tbsp of oil for cooking the egg, followed by ~3tbsp of oil for stir-frying.

Process, Chaolamian:

Video of the frying of the noodles is here if you’d like a visual to follow along.

Crush the garlic, slice the onion and chilis into slivers, chop the baby bok choy, beat the eggs. For the baby bok choy, cut slice the bit that ‘holds it together’ at the end, then chop into ~1 inch sections across the stem. For the eggs, really beat the snot out of them until no stray strands of egg white remain.

Scramble the egg. However you want, I guess. But if you want to follow us, first Longyau: get your wok piping hot, shut off the heat, add in your oil (here about 2-3 tbsp) and give it a swirl to get a nice nonstick surface. Swap the flame to medium, then heat the oil up until it’s bubbling around a pair of chopsticks. Pour in the egg, let it puff, then pull the cooked portions to the sides of the wok, letting the uncooked bits set in the center. Then once it’s ~80% not runny… flip it. Shut off the heat, quick scramble, and reserve.

Boil the noodles. Boil the noodles as per the recipes above, or whatever sort of package you’re working with.

Stir fry the noodles. As always, first longyau. Piping hot wok, flame off, ~3tbsp of oil, swirl. Flame on medium then, immediately:

Garlic, in. Fry for ~30 seconds til fragrant. Scooch the garlic up the sides of the wok.

Shut off the heat. Add the tomato paste and chili bean paste. Swap flame back to low. The reason we shut off the heat before adding the pastes is because those guys love to burn.

Fry for ~2 minutes until the pastes have stained the oil obviously red. Up the flame to medium.

Baby bok choy, in. ~30 second fry until slight wilted.

Noodles, in. ~30 second fry until it’s all basically mixed.

Swirl the tablespoon of soy sauce over your spatula and around the sides of the wok. Super brief fry.

Salt and five spice powder, in. Super brief fry.

Onion/peppers in. Quick ~15 second fry.

Add back in the egg. Super brief fry.

Swirl the half tablespoon of dark Chinese vinegar over the spatula and around the sides of the wok. Super brief fry.

Heat off, drizzle the toasted sesame oil. Another mix, then out.

Quick note to fellow Lamian geeks re dough conditioners:

Forgive me for getting into the weeds for a second here, and definitely skip this if you don't live-and-breathe noodles and such.

See, there’s been a subset of us Lamian nerds online that’ve been arguing about how best to make pulled noodles outside of China for, like, the better part of a decade. I’m feeling a little lazy to bump the ol’ eGullet thread though, so forgive me for chiming in my two cents here.

Recently, I’ve seen a lot of hype surrounding adding either L-cysteine or nutritional yeast to the mix in order to get a pullable noodle. The former seems to be from reports that certain noodle shops in southern Japan use it as a conditioner, the latter from Tim Chin’s recent (very cool) SeriousEats article on the topic of Lamian.

I do have my doubts that either of these two additives alone could make a pullable alkaline noodle – Tim’s SE recipe specifically states that it (i.e. the deactivated yeast) can’t. I certainly understand the desire to make a Lamian recipe that doesn’t call for minuscule quantities of weird shit like Sodium Metabisulfite – on that note, I think Tim’s deactivated yeast is bloody brilliant. But it is still missing something, of course, else it’d also be able to pull with the addition of Kan Sui.

The thing that I think these reducer-focused recipes are missing is the emulsifier. On a whim once we tried applying solely salt plus a sprinkle of sodium metabisulfite to the dough, just to see what would happen. Adding that much reducer undeniably turns the dough into puddy, but after a pull or two the noodle still broke. The effect is a little hard to describe, but it feels like the dough loses its integrity… like a Chenmian that’s been sitting in the back of your fridge for a week. You need a stronger noodle – and that’s where the emulsifier comes in.

Emulsifiers function as dough strengtheners. How exactly they differ from oxidizing agents, and why they don’t seem to sacrifice extensibility are both good questions that are beyond my pay grade. There’s a pretty good 2019 article on the subject of STPP in noodles called “The effects of phosphate salts on the pasting, mixing and noodle-making performance of wheat flour”, link here. Adding STPP, particularly between the levels of 0.05% and 0.1% (note: we were at 0.04%), caused “an enhanced resistance to successive mixing and an improved capacity to sustain shear force”. I could certainly be misreading the paper (I uh… majored in Finance lol), so definitely don’t take my word for it, but the fact remains that the emulsifier seems to be an important component.

Because you know that classic blue bag of Penghui? These days it’s not the only name in the game. There’s another mix from a company called QBR that’s relatively popular and also works like a charm. Their mix? 42% sodium chloride, 35% sodium carbonate, 8% potassium carbonate, and 15% acetylated distarch phosphate.

What’s acetylated distarch phosphate? …an emulsifier. Why are they bonding phosphate to a modified starch instead of using a phosphate salt like STPP? No clue. But notice, there ain’t a single reducer in that mix.

Because really, relaxing a dough’s easy. As evidenced by Chenmian… all you need is time, really. Keeping an alkaline dough from breaking after multiple pulls? That’s the ballgame.

In the future, I hope someone can come up with a similarly brilliant solution to the emulsifier problem as Tim did for the reducer. I do wonder if lecithin (potentially in combination with the nutritional yeast) might do the trick – if it does, people could potentially bake some baking soda to get some sodium carbonate, then everything needed for Penghui could be available at supermarkets in the West. Purely speculation though.

Lamian: What to do if you fail

Oh no! You failed your Lamian. C'est la guerre. You hungry? It’s ok. You can still eat dinner.

If you have a pasta maker… fold the dough a couple times then pass it through, I dunno, the third smallest setting. Then cut it using the 2mm setting. Now boil.

If you don’t have a pasta maker, roll the dough out thin, then fold it a few times until the whole thing is roughly the size of your knife. Then cut it into ~2mm strips. Now boil.

We ate a lot of failed test batches. They’re still pretty tasty noodles to be honest. It’s not ideal because these failed batches end of breaking kind of easy when boiling, so sometimes you can have these weird ~5-6 inch long noodles. They won’t impress anyone, but hungry people definitely won’t complain.

Not hungry? Just want to practice a bit more? Press your failed noodle together, then apply a bit of penghui to the dough, starting from step five. The additional Penghui will bring the dough to life – often Lamian shops’ll keep some dough in the fridge, then add some additional Penghui, and start with the gluten combing step when people order a bowl of noodles. You can use this trick to practice repeatedly with one batch – that way, you can work on your skills repeatedly without wasting ~an hour of your life each time. At some point, the Penghui’ll get too much and you’ll need to toss the dough, but hey, these components are pretty cheap anyhow.