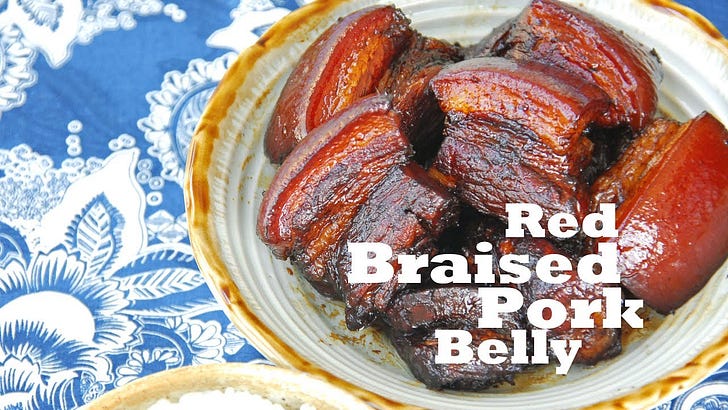

In this post, we wanted to show you guys how to make a classic homestyle dish - hongshaorou or “Red Braised Pork Belly”. If you peaked in these threads before and were intimidated by some of the specialty ingredients, this might be an easier dish to replicate. There’s nothing in here that you couldn’t find at, say, a Wholefoods.

Now, homestyle hongshaorou is one of those dishes sort of like gumbo in that there’s a million different ways to make it. Every family’s got their own recipe – what spices are used, how the sugar’s used, how much soy sauce, what size the pork cuts are, etc. The basic commonalities for this dish are (1) use pork belly (2) braise in a sweet sauce for 60-90 minutes (3) flavor with ginger, cassia/cinnamon, and star anise. Everything else will change depending on the region and the cook.

For this dish we got a guest cook Rob (who uh... understandably wants to keep his reddit account anonymous), who recreated this awesome dish from his Hunan friend’s family recipe.

Ingredients

Basic Ingredients:

Pork Belly (五花肉), ~600g. In an ideal world, you’re going to find some pork belly with skin on. The best pieces for this dish are about half lean, half fat, and a sliver of skin. But because this isn’t an ideal world, don’t stress if you can’t find pork belly with the skin.

Ingredients for your Braising Liquid:

Crushed Rock Sugar (冰糖) or brown sugar, 80g. This is a key ingredient for the dish, and we decided to go for some authenticity bonus points and use rock sugar. If you can’t get rock sugar, brown sugar completely works here as well. The flavor is obviously slightly different, but it’s real tasty either way.

Liaojiu (料酒), 1 tablespoon. A.k.a rice cooking wine, huangjiu, or Shaoxing rice wine. Feel free to be liberal with your potential substitutions here.

Dark Soy Sauce (老抽), ¼ cup. This is going to form the base of our braising liquid. Now, there’s generally two schools of thought when it comes to this dish – do you want a deep, dark color like we have, or do you want to aim for that light brown almost ‘reddish’ color? We love the color and flavor of the former, so that’s what we’re opting for here. There’ll be a discussion on the differences between this style and ‘Mao-style’ hongshaorou in the notes below.

Light Soy Sauce (生抽), 2 Tablespoons. Light soy sauce has a sharper saltiness to it than dark soy sauce, so we’re adding this mostly for salinity.

Water. I should’ve measured this amount, but you’re looking for enough water to reach halfway up the uncut pork belly when boiling it in step #1.

Ginger (姜), ~25g. Peel and cut into slices.

Garlic, 2 gloves. Crushed.

Star anise (八角), 2.

Cinnamon or Cassia bark (桂皮), 1/2 stick. The reason these guys are basically interchangeable is what we get as ‘cinnamon sticks’ on the international market is actually cassia. The characteristic ‘curl’ of the stick that we get abroad vs the shreds of ‘bark’ that you’d find in China depends only on the method of harvesting. If you actually have true cinnamon I’m sure that’d be tasty too, just watch your balance and make sure it’s not dominating the dish.

Dried Sichuan Chilis (大红袍), 2. Cut in half and deseeded. You could sub dried Arbol if you're abroad and can’t find these. This is a Hunan variety of hongshaorouwhich is why the chilis are included, but note the dish isn’t spicy at all – the chilis are basically just for some subtle flavoring.

Sichuan Peppercorn (花椒), ~12. Similarly, we’re using Sichuan pepper, but this small amount ain’t gunna get you any sort of numbing sensation. Same deal, subtle flavoring. I hope you have some whole Sichuan peppercorn into your pantry… but for this dish you could skip it or toss in few whole black peppercorns if feel so inclined.

Process

Briefly boil the Pork Belly. Add enough water to a wok or pot to get halfway up the pork belly – this doesn’t have to be exact, but we’re going to be using this water later in our braise so try to aim for roughly that amount. Boil a minute or two on each side, until the outside changes color and firms up. The reason we’re doing this is to allow for easier cutting, as the structural integrity of your pork slices is critical to making a tasty hongshaorou (especially if your knife isn’t extremely sharp, sometimes the fat can separate from the lean while cutting). Reserve the hot water in a separate pot - preferably a claypot.

Cut your pork belly into chunks. The size of your chunks totally depends on your preferences – we like big thick cubes (about 2 inches each side), but some people prefer to cut each of those chunks into four smaller pieces. Regardless of what you’re aiming for, the important bit is the ‘height’ of your pork pieces - you can get a visual at 1:23 in the video. You want to have a nice cross-section roughly two inches high that has a solid mix of lean, fat, and a slice of skin. If you have some extra lean, cut that up into chunks too; if you have some extra fat, toss it or render out some lard to use as the base of the braise.

Fry the chilis and Sichuan peppercorns, then add these and the rest of your aromatics to your pot of water. So briefly fry the Dried Chilis and Sichuan peppercorns. After they’re nice and aromatic (about a minute or two later), toss it in to that reserved water along with the garlic, ginger, cinnamon/cassia, and star anise. Now, this is my buddy’s recipe, and I personally would’ve also fried the ginger and garlic along with the chilis and peppercorns. Obviously it didn’t make too much of a difference to the end result though, so it’s all good.

Make your ‘caramel’. This is a critical step. I wasn’t sure how to translate this, the method is called chaotanse in Chinese. To that oil, you’re going to add half (40g) of your crushed rock sugar (or brown sugar). Over low heat, melt your sugar into the oil until it’s melted into the oil and a nice dark brown color. This’ll take about five minutes, but don’t walk away – the sugar can burn real easy, going from zero to midnight in a blink.

Fry the pork in in the caramel. Add your pork chunks and get a nice coating for caramel on each side of the pork pieces. You gotta be real careful with the pork... don’t be overly aggressive, as you don’t want the pieces to come apart. In the video, we actually probably could’ve gotten a nicer coating of caramel, but we were a bit paranoid about the pork structure.

Turn off the heat, add in the liaojiu and the soy sauces, the transfer to the pot. The reason we used the previously boiled water from step #1 as the base of the braise is because at this stage, it’s critical that the water that is added to the pork is hot. Otherwise, the pork can tighten up and become tough. So instead of bringing hot water to the pork, we save some time and just bring the pork to the hot water.

Braise the pork, covered, for 90 minutes. Try not to peek too much here, just check on it every 30 minutes or so. Your pork will be done one a chopstick can pierce the entire piece of pork with very little resistance. Take a look at 5:11 in the video for a visual of what a done piece of pork looks like.

Add in sugar, and reduce uncovered 20 minutes (if not using a claypot). Add the second hit of your sugar (rock sugar or brown sugar) and let it dissolve into the sauce. Something that we found is that if you’re using a pot with a heavy lid (instead of a claypot which can breathe a bit), you might need to let the sauce reduce a bit so that it thickens up a touch. We’re not looking for a sauce that’s super thick or anything, but rather a thin sauce that has a bit of adhesiveness.

Remove pork, strain sauce into separate bowl. We’re not serving the sauce with the pork – this ain’t hongshao soup. Brush the pork with the sauce to get a nice sheen, and then drizzle a spoonful of the sauce over top. Obviously don’t waste the sauce though – we took some hard-boiled eggs and soaked them in it overnight for breakfast the next day.

Serve. Eat with rice, a fried veggie, and some cold beer.

A note about equipment:

The best way to cook this dish is in a claypot – the claypot still traps steam pretty nicely, but will still allow for some moderate reduction as it’s cooking. Unfortunately, our claypot recently broke, so we used a Western-style cast iron Dutch oven – the heavy lid was great for cooking the pork, but required us to reduce the sauce a bit more after we were done braising. Honestly, basically any vessel that has a lid is totally cool (many people just use a flat-bottomed wok), but each will have their own quirks so just use your common sense.

Also, some people like to help preserve the shape of the pork by wrapping it with twine. This is a great idea and probably something we should’ve done here, but… this is a homestyle dish and we were feeling lazy.

A note on different types of Hongshaorou

There’s a bit of regional variation here. Probably the most famous style of hongshaorou is ‘Mao-style’, which uses similar seasoning as ours but wouldn’t use any dark soy sauce (and add some salt and cut the light soy sauce in half). If you want that light ‘reddish’ color, go for that and keep everything else the same.

Also, depending where you are in China, some places wouldn’t use chilis or Sichuan peppercorns. Some places would add in green onion and vinegar. There are variations where people toss in water chestnuts or serve on pickled mustard greens. So once you get the basic recipe down, go nuts and make it your own.