"Inches of Ginger", and why recipes choose to be 'unscientific'.

...is it really so hard for recipe writers to just use grams?

I always like to read through those “things recipes do that annoy you” threads that pop up on /r/cooking every now and then. I’ll confess that it’s partly indulge my latent Dunning-Kruger-laced superiority complex – to smugly pat myself on the back for using the term “caramelized onion” correctly, for not underestimating prep time (I don’t even list prep time, how about that!), and so forth. But there’s also a more productive element to scrolling through those threads… which’s to figure out the issues people have when following recipes, to try to better hone my craft.

I’ll give you an example. One commonly listed complaint is that many recipe writers don’t seem to re-list the ingredient quantities in the body of the recipe itself – the quantity is given in the ingredient list (e.g. “Ground nutmeg, ¼ tsp”), and then in the process they’ll simply state “add the nutmeg”.

For vast, vast majority of the time I’ve been sharing recipes, I’ve been squarely an “add the nutmeg” sort of guy. Because personally? I practically never interact with a recipe by having the thing in the kitchen physically beside me, dutifully following the process steps in order like an arts and crafts project. It’s just… not how I use them. The way I’ve always interacted with recipes is this:

Find a recipe – or a handful of recipes – that seem legit.

Read through the recipes(s).

Build a mental model of what’s going down, and how I’m going to execute the thing in my kitchen.

Scribble down some notes on a piece of paper or in my phone.

Cook, referring to the notes when I have to.

It’s just the way my brain works, I guess. It was a similar process for me in school, too – everything would go in one ear and out the other until I started getting serious about taking notes. I need the knowledge to… “become mine”, so to speak.

So for the longest time, I just couldn’t get the people that complained about “add the nutmeg”. I couldn’t shake the feeling that they were doing it wrong. I mean… cooking’s all about Mise en place, right? You know, French for “get your shit together first”.

But as the years have mellowed me out, I’ve relented. Because… there’s not just one way that people learn stuff, right? It literally costs me nothing to write a recipe as though I was writing a YouTube voiceover – i.e. with the quantities included – and if it’s helpful to absolutely anyone, why not?

So I’ve started to reapproach things. I try to listen. Sometimes people’s annoyances are contradictory, and there’s nothing you can do but take a side. As an example, some people prefer “one onion, divided”, while others prefer “half onion” listed twice. I’m pretty sure the former uses the ingredients list as a shopping list and the latter uses it to organize their mise, and I think the latter are more important to cater to. But for the most part, it’s easy enough to swallow my pride and preferences, and just go with what people actually want.

All of that said, there is one contradiction that I don’t think can be squared.

One inch of ginger.

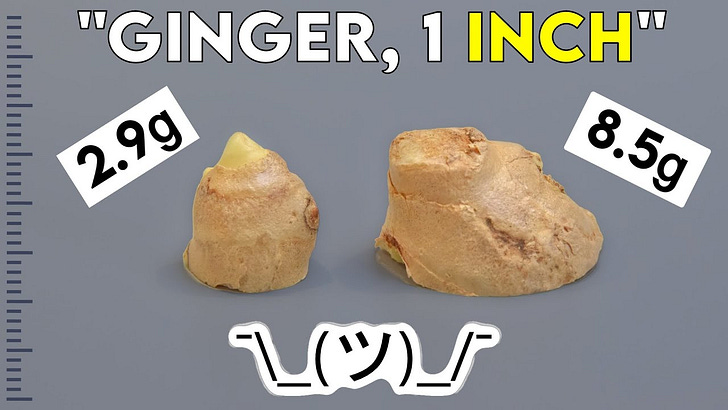

Here’s a picture that I snapped of some ginger. I grabbed my measuring tape, and cut out one inch worth of ginger.

The ginger on the left is 2.8g.

The ginger on the right is 8.5g.

Which… makes sense, yeah? I mean, ginger’s a fucking three dimensional object, right? Nobody’s going around writing recipes with “inches of chicken breast” or “centimeters of carrot”. This has be some sort of culinary malpractice…

If you’ve made it this far, I owe you a simple explanation just in case you need to move on with your life:

An inch of ginger is an approximate measurement. It’s a little like saying a “clove of garlic” – you can have small cloves, you can have large cloves. In the end, the quantity just… is not that important.

How gingery your ginger will also depend on the age of the ginger (older = more gingery), how finely you mince it (more finely minced = more surface area = more ginger), etc etc. And even if all the variables cut in the same direction, (1) that 5.7g of ginger probably isn’t going to make or break your dish and (2) if for some reason it is a touch too gingery – a problem I struggle to remember ever having – you can add a small sprinkle of sugar or MSG to balance it.

So maybe you agree that it’s not all that important, but why would I choose to use a sort-of-silly approximate measurement? If I have the ability to write “add ¼ tsp nutmeg”… certainly I’d also have the ability to toss the ginger on a scale, weigh it out to 5g, and write that, yeah?

Why everyone loves by-weight measurements.

Let’s take a look at a recipe: this is a recipe for curry by the always-excellent Kenji Lopez Alt.

When I first started cooking, The way I used to do this – the way I think a lot of us were taught at least in America – would be to begin checking items off my ingredient list, stacks of measuring cups and spoons in-hand:

I’ve got one and a half teaspoons cumin, so I’m grabbing my teaspoon, I’ve got a quarter teaspoon ground nutmeg, so I’m grinding then trying to shuffle it in to my quarter teaspoon… now this is ¼ cup of lime juice, so I’ll grab my Pyrex, now I’m chopping up cilantro and filling up a half cup…

Let’s be honest, it’s a pain in the ass. But if you’ve done any serious baking, you’re probably aware of a better system: measuring by weight.

Much ink has been spilled on the accuracy benefits of the system, but what’s talked about less is that it’s also… easier. There’s no fumbling around with cups and tablespoons. You:

Put a digital scale down on your counter.

Put a bowl on the digital scale.

Put ingredients in the bowl, tare in between each ingredient.

Less dishes. Less stress. More accuracy. More replicability. It’s used in serious baking recipes. It’s used (in China, at least) in professional kitchens.

…why the fuck don’t we do this for everything?

The limitations of by-weight:

The reason, in my view, is that by-weight as a system isn’t competing with ‘by-volume’: weight is unquestionably better. It’s competing with ‘by feel’ (or alternatively, ‘by experience’).

Stay with me here. Let’s talk about baking, and that all-too-common trope that “cooking is an art, baking is a science”. There’s this sense amount a lot of people that when you’re cooking, you can go by feel, but with baking the recipe Must Be Followed To The Letter.

It’s not a terrible heuristic, but it’s easy to overstate the case. Because… how exact is baking, really?

Here we’ve got two brands of flour – they’re Chinese flours as that’s what we’ve got, but you could also do this experiment yourself with Gold Medal and King Arthur.

On the right is 100g of a brand called Sai Bei Xue (a brand renowned for La Mian making). On the left is an equal amount of one called Arawana (which I believe is available at Chinese supermarkets in the west?). This is what they look like after we add 50g of water to them:

The brand on the left can absorb almost 10g more water than the flour on the right. In the context of dough making, that’s… huge. If we were making a Bao recipe using the flour on the left, but you were using the flour on the right, we would get drastically different end results. Even something as fundamental as how much water your flour can absorb can depend on the type of wheat that’s used, how fresh it is, how finely milled it is.

Now, there’s certain ways that you can control for this. For example, the aforementioned King Arthur flour is known for being quite thirsty, i.e. it can absorb a lot of water. So on their website, they’ve got a whole database of recipes that’re calibrated specifically to King Arthur flour. Another thing that we could do is explicit specify our brand of flour, a move that I’ve seen from some recipe writers.

But this can quickly spiral out of control, because where do we stop? Do I need to call for Donggu soy sauce and not Kikkoman, because I use the former? How MSG-y your MSG is, how salty your salt is – even these can depend on the brand you chose back at the supermarket.

We could, of course, list each product that our recipe was calibrated for. We could specify how and how long the ingredients should be stored. We could inform you of our ambient temperature and air pressure. And so on.

But attempting to minimize all of these variables I think? It’ll will quickly lead us to something like that infamous 26 page brownie recipe from the US army. It’s 26 page recipe because it’s not a recipe – it’s a technical document that details a standardized manufacturing process.

But there is another way.

By Feel Measurements

Going ‘by feel’ doesn’t have the most fantastic of reputation in a lot of cooking circles online. I think everyone knows of some story of a family recipe being saved by taking their grandma’s “pinch of flour” and physically moving it over to a tablespoon. There’s something that feels profoundly anachronistic about ‘by feel’ the 21st century – we live in A Scientific World, and A Scientific World would never feed itself with pinches, sprinkles, and slugs.

Except – given the epistemological uncertainties I outlined above, given the absence of truly replicable standards… quite often pinches, sprinkles, and slugs can lead us to an equally if not *more* consistent end result. Because at the end of cooking?

You’re going to taste your food – and calibrate.

In our videos, we list out the specific amounts that we’ll add to marinades and such (½ tsp salt, ½ tsp soy sauce…) – when we’re cooking for ourselves, we almost never measure these things. Because after you do it a couple times, you can start to get a sense for roughly the amount that you need to toss in, and then you can go from there. This will not be exactly the same amount every time, and that’s fine.

It's the final tasting step that’s crucial. Maybe today you didn’t add enough salt, so… you add more salt. Maybe it tastes a little flat – you can add pepper or vinegar. Maybe it’s a touch harsh – you can mellow things out with sugar or MSG. Does it feel like it lacks depth? You can add a little bit of all of the above.

Of course, in an endeavor like baking, you can’t calibrate based on a final tasting – that wide gap between ‘intermediate product’ and ‘final product’ is what makes it a more demanding pastime. Instead, you need to make judgements based off of texture: you knead the dough until it arrives at a certain degree of smoothness, you proof it until it bounces back to certain degree when given a poking.

For the beginner cook, I know that all of this can seem overwhelming. How do you know what the right degree of smoothness is? How do you know what the stir fry should taste like?

We’ll get to that in a second, but in the meantime, have comfort that you already are likely making judgements in the kitchen based off of feel and intuition. Is the clove of garlic a little small? Maybe I’ll use two. Is this mince a little rough? Maybe I’ll give it a few more chops. I doubt most people are setting a timer when they’re frying their garlic – you’re frying it until it feels right.

Learning by feel

Now swing back to Kenji. Why’s his curry using ‘by volume’ measurements again?

Well, if we can agree that (outside of certain professional situations) the ultimate goal is to go by feel, the question is… how do you get there?

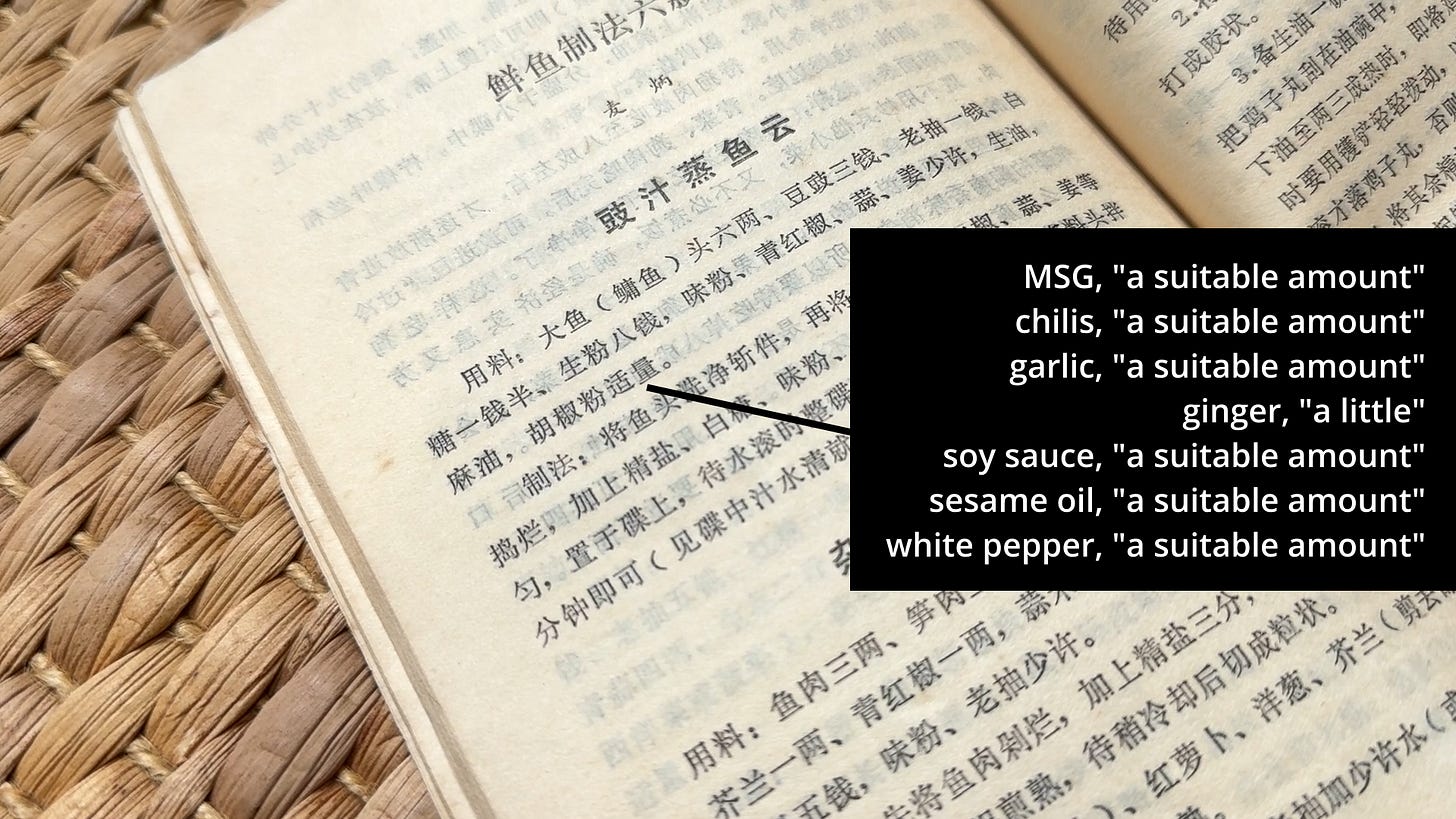

In a lot of old timey recipes, the authors will assume a certain degree of cooking knowledge on the part of their readers. In old Chinese recipes, this manifests itself as the dreaded “适量” – i.e. a “suitable amount”:

This isn’t just Chinese recipes though, a lot of old western recipes skimp on the measurements too. There’s a fascinating cookbook called The Lost Art of Real Cooking, where the authors endeavored to recreate modern recipes by communicate them in that old, folksy, ‘by feel’ way. I wholeheartedly suggest the book to everyone, but one of my personal takeaways was just how… obnoxious a lot of the recipes sounded:

This isn’t an indictment of the authors. It’s totally a fun intellectual exercise, and the above might be helpful for a certain kind of reader. But I do think it neglects the key, fundamental difference between old timey recipes and modern recipes – old recipes were designed to inform an experienced cook how to make a new dish, modern recipes must teach at a variety of different skill levels.

You so need a starting point.

And volume? Makes for an excellent starting point, for a couple reasons:

We’re visual creatures. I don’t know about you but, I’m still not very good at estimating the weights of stuff. “Grab a tablespoon worth” is a lot easier than “grab 100 grams worth”.

No matter where you are in the learning process, you generally need to move ingredient --> container with *something*, and that’s generally some sort of spoon. And that spoon might as well have a standardized measure. Over time, the tablespoons of sugar can morph into scoops.

When you learn mathematics in school, you don’t start off with number theory, or even formal logic. You start with basic operations that you can apply to your life almost immediately.

But you also might not want to start kids off with some sort of CAS graphing calculator. They’ll use them eventually – and learning to use these sorts of tools is important – but it’s critical to develop an intuition to mathematical thinking first.

Ditto with recipes. I think we should think of them all a little less as ISO standards, and a little more like lesson plans.

So… how much is an inch of ginger?

About 5 grams, or a bit less than a knob.

Thank you thank you , thank you for this article! I have been teaching cooking in Italy for 22 years and I am still baffled by cups and measuring spoons even though I try to convert my recipe from grams/ml to volume measurements. I have always been obsessed by things like a cup of chopped bananas or a cup of chopped nuts, that is an impossibility! For flour however, I show them how to determine the % gluten based on the nutritional label on the package and tell them that the more gluten the more liquid is absorbed. It's a tip that is always appreciated.

Agreed. I generally do prefer measuring by weight but the problem is if you accidentally put in too much and can’t easily take it out. With bread it’s easy enough, I skim that bit of extra flour off the top without touching the wet ingredients. But if it’s a liquid… well…

It’s also hard to be extremely precise about grams sometimes too. I find that a tsp table salt can differ wildly as to weight (or maybe I need a new scale). And it’s rare that I get exactly 250 g of flour, it’s usually more like 248 or 253 g.