This recipe is adapted from a 1972 cultural revolution era cookbook, and it’s my favorite Sichuan hotpot.

If you’re familiar with Sichuan hotpot today, you probably know it mostly as… an eating experience with a certain degree of intensity. A cauldron of bubbling spice. A haze of flavor and pain clouded by steam, baijiu liquor, and the numbingness of Sichuan peppercorn. The type of meal where young dudes one up eachother based on how spicy they like their pot; the sort of meal that the late Anthony Bourdain characterized as a gastronomical SM session.

And while, I think, people can sometimes go a little far with the stereotype… it’s not a wholly inaccurate picture of Sichuan hotpot in 2024. It’s a dish with a bunch of the knobs dialed up to 11. There’s a lot going on: Sichuan hotpot today is a whole cacophonous infusion of not just Chilis and Sichuan pepper, but a whole smorgasbord of aromatics, fermented pastes, and stewing spices.

And don’t get me wrong, I definitely do love this sort of hotpot. If you’ve never tried it, add it to the top of your list. If you don’t happen to have a restaurant close to you, the phenomenal Wang Gang has a pair of recipes that jive with all the research we’d previously done on the topic. I’ve never made it myself – there’s a similar degree of intensity to the cooking process – but I’d say it’s well worth the project if you’ve never had the experience.

But for me? This sort of pot is also… simply just plain something I can’t have on the regular. Nobody wants to drop acid on a Tuesday.

Enter?

Historical Hotpot

In the grand scheme of things, that sort of dial-things-up-to-11 Sichuan hotpot? It’s actually sort of a newer invention – likely a consequence of the post-Reform-and-Opening explosion of Sichuan restaurants throughout China in the 80s and 90s. Even as recently as 1984, if you popped open a Sichuan cookbook you’d find a simpler style of pot. It’s less packed with spices, a bit less heavy handed with the chilis and Sichuan pepper too.

It’s more or less just:

Ginger

Chili Bean Paste

Fermented Soybeans

Sweet Fermented Rice

Rock Sugar

Chili Peppers

Sichuan Peppercorn

Tallow

Beef Stock

… and that’s basically it. It’s got a certain level of heat to it, but I’d characterize it as more ‘savory’ than anything. It’s spicy, sure, but ‘comfortable spicy’. For me, at home? It’s just… a better meal.

And that’s largely because - seemingly from the ground up - the whole pot was designed to be eaten along with rice.

In this (beautiful) old picture, in the lower right hand corner you can see pretty clearly that our handsome diner is accompanying this meal with a bowl of white rice. And… that’s no accident. Classically, right alongside the still-common mainstays of beef or tripe, you’d also blanch a handful of aromatics as well (either Green Garlic or Scallion depending on where you were in Sichuan). That beef and aromatics - after a quick dunk in toasted sesame oil – are then scarfed down in a singular bite along with your rice, sort of akin to how you might eat a Mapo Tofu today.

While it might not be immediately obvious, it's actually a drastically different view of the dish. Instead of the pot as a vehicle to fill up on meat, you’re using a bit of meat and a bunch of aromatics to fill up on starch. Sichuan hotpot today may be a raucous carnivorous blowout that leaves you in cold sweats, but in the past the whole thing was more of a soothing everyday meal. It was a classic with-rice-dish.

‘With Rice Dishes’

There’s a term in Chinese called ‘xiafan’ (下饭) that’s incredibly difficult to translate. Fuschia Dunlop translates it as dishes that help “send the rice down” (an accurate but awkward translation), we translate it as “over-rice dishes” (a more natural but less accurate translation). Basically, it refers to things that help you eat a lot of rice.

But that’s a concept, I think, that might feel borderline alien to the modern Westerner. After all, most of us grew up in a post-Atkins world. Even for those that aren’t diabetic, or on the whole keto or low gluten train… there’s still this overall cultural sense that starches are something bad for you. Like sugar, they’re something to be minimized. They’re a special little treat. If you’re like most people, maybe you might need help eating vegetables; or perhaps if you’re a bodybuilder trying to bulk, maybe you need to figure out ways to get down ever-increasing quantities of canned tuna. But starch? Piling on extra rice or bread is something that you do on holidays – you certainly don’t need help eating them.

For a lot of human history though, the situation was obviously the reverse. Unless times were particular bad, rice was something that everyone had. It’s how you got full. Your staple grain was something that you had every day, and it was also something that was very easy to get bored of. So especially on the lower end of the income spectrum, a lot of foods in China could be conceptualized as strategies to combat that boredom, that sensory-specific satiety. Whether doing so inferred a long term survival advantage, or whether it was - occam’s razor - just plain tastier… the end result is that you can find a bewildering number of humble xiafan dishes across China (and even Asia at large).

This is the cultural context of the first Sichuan hotpots.

The Humble Origins of Sichuan Hotpot

The upper reaches of the Yangtze river are an interesting place.

The Yangtze river, of course, has always been one of the primary arteries of the Chinese empire. But like many of the world’s rivers, the farther upstream you go, the less navigable it becomes. For a lot of the world’s major civilization bearing rivers, that tends to be the end of the story – once the Pearl River or the Nile turn treacherous, trade slowly begins to peter out. But right about where the Yangtze river boat travel turns ‘possible but a little dicey’, the system hits the Sichuan Basin and its fertile, alluvial soil. So, trade continues – even if it means that the boats need to be dragged up-river by hand.

And as a result, there’s a certain… working class character to the whole region that, I think, ineffably shaped the culture of the river towns that sprang up in the wake of that trade.

It’s a little hard to describe – I’ve always felt that there’s a sort of ruggedness to the Sichuanese cities along the Yangtze that you see a bit less in the rest of Sichuan. Chengdu, Leshan, and Zigong are pleasant. Chongqing, Luzhou, and Yibin are gritty. And I think it might not quite be a coincidence that the latter is where one of the world’s great with-rice-dishes was borne.

While the overall concept of a hot pot is certainly nothing new, spicy Chongqing hot pot is thought to have hit the scene sometime in the late 19th or early 20th centuries, likely around the docks in the poorer section of town – Jiangbei (or perhaps Jiaochang, another working class neighborhood). Originally, the dish used old water buffalo, i.e., the cheapest protein you could get your hands on. Right on the street, they’d bubble up a spicy broth in one of these sorts of divided pots:

The original name was Shuibakuai (水八块), “Eight Piece Water”, called that way either because the pot was divided into eight sections or because classically you could get eight pieces of meat for just one coin. It got so popular on the street that on the other (richer) side of the river, people began to open small restaurants serving up what’d still be recognizable today as ‘Sichuan hotpot’.

And by the middle of the 20th century, that pot had spread to Chengdu (where they made their own twist on the thing), points elsewhere in Sichuan, and even Shanghai and Beijing. But that mid century version was the fermented soybean heavy, savory, over-rice variant that we’re sharing today – not what you’d get if you hopped off the plane and grabbed a hotpot in Chongqing in 2024.

Modern Hotpot

We’re not sure when exactly things changed. The recipe below is from 1972. As we said before, even as late as 1984, the classic Sichuan cookbook “Dazhong Chuancai (大众川菜)” had this style of hotpot inside.

If we had to guess, the alterations likely came during the explosion of Sichuan restaurants throughout China in the 1990s. These restaurants leaned heavily on Jianghucai – that is, the so-called “Lake and River-style Sichuan cuisine”. This style of Sichuan food is a sort of modern commercialization of what was previously the more… common people’s dishes (“Lake and River” in Chinese conjures up images of the untamed, an antonym of sorts to “Palace and Temple”). A whole swath of what you might think of as ‘classic’ Sichuan dishes - Sichuan boiled fish and beef, Sichuan spicy chicken, Suan Cai Yu, etc - belong to this category, and hit their modern stride during those decades. The dishes often leaned closer to the Chongqing side of the Sichuan cultural sphere, were standardized in order to better commercialize, and quite often, for one reason or another, seemed to really load up on the chili peppers.

But when it comes to hotpot, it’s not just the intensity of the spice – there’s a strong element of spectacle at a modern day hotpot restaurant, whether Sichuan or otherwise.

Probably the most obviously example in China is the famed, beloved-by-many chain restaurant Haidilao. Their hotpot base was always ok enough, but fundamental to their explosion of popularity in the 2010s was their “service”. It was a place where you could order from little iPad menus before that was a thing. If you had to wait (and there was often long queues), they had little nail salons by the entrance so that you could get a mani-pedi; when you ordered fresh noodles, dancing noodle boys would swing by the table and theatrically pull them into the pot. If it was your birthday and you came alone, they’d sometimes prepare comically large teddy bears for you, so that you didn’t have to hotpot by yourself.

Now, the food snob in me would sometimes roll my eyes if someone said that it was their favorite restaurant, but… the older get, I gotta admit, Haidilao was actually pretty fun.

But even in the world of the more ‘serious’ Sichuan hotpot, there’s actually always been similar dynamics. The intensification of the soup itself is an obvious example, but places would compete based off of different ingredients you could add (e.g. meticulously anatomical cuts of meat that would put a vet to shame), different pot bases (e.g. many spicy level challenges worthy of a First We Feast episode), etc. Recent years have seen a dramatic expansion of the dessert menu: restaurants found that people enjoyed having some bingfen or laozao along with their meal, and that’s quickly ballooned to… this:

Similar deal with sides, which’re also sometimes starting to enter into meme food territory, like… this qianzhang tofu sheet ‘lasagna’:

Now, I want to be clear here: there is absolutely nothing wrong for restaurants to be fun. Against the backdrop of the social isolation of the modern world, restaurants are where we have to gather. From hotpot, to Japanese Izakaya, to Hong Kong Chachaanteng, to those American hipster joints with graffiti on the wall, craft beer, and some sort of ambiguously Mexican-Asian fusion menu… I like this stuff. Even if the price was the same, I’d much rather enjoy some deep fried peanut butter stuffed French toast and bubble tea with friends in a raucous Chachaanteng then I would a technically correct braised abalone over some white tablecloth alone.

But it’s a little like going out to the movies. If I’m at the IMAX, I want to see Christopher Nolan’s latest spectacle. When I’m at home, I’d rather snuggle up and watch something cozier, or at least something with intelligible dialogue. Perhaps Steph’s favorite movie of all time, A Pigeon Sat on a Branch Reflecting on Existence, or maybe something classic like Kubrick that fits better on a smaller screen.

To strain the analogy, this 1972 recipe is the hotpot equivalent of a Kubrick flick.

Chongqing Hotpot

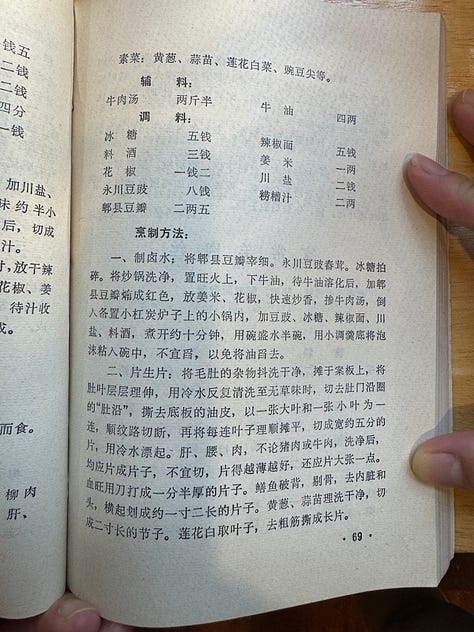

There was a slight degree of adaptation here. For those of you that can read Chinese, here’s the full disclosure:

The TL;DR is that we (1) doubled up on the Sichuan peppercorns and chili (2) seasoned with more salt, as well as adding in a non-negligible amount of chicken bouillon powder, (3) cut the quantity in half. Small adjustments so that the pot could go even better with rice, mostly.

Vegetarians are welcome to swap the beef components here for vegetarian equivalents – simply swap the tallow for peanut or rapeseed oil, and the beef stock for a vegetarian stock. For the keto folks in the room, there are probably better Sichuan hotpot recipes out there for you.

Ingredients:

For the base:

Tallow (牛油) or your oil of choice, 100g. Sichuan caiziyou (菜籽油) - i.e. unrefined rapeseed oil - is another traditional choice. If neither are available to you, lard or peanut oil would be untraditional, but tasty.

Chili bean paste (郫县红油豆瓣酱), 60g. Minced or pounded.

Ginger (姜), 25g. Minced.

Douchi, Chinese fermented black soybean (豆豉), 15g. Minced or pounded.

Rock sugar (冰糖), 8g.

Spicy Dried Chilis, e.g. Sichuan millet chili (小米辣), Thai Birds Eye, Peri Peri, etc 10g. Ground into powder.

Red, Fragrant chili, e.g. Sichuan bullet chili (子弹头), Guajillo, etc 5g. Ground into powder.

Sichuan peppercorn (花椒), 5g.

Laozao, fermented rice (醪糟), 50g.

Liaojiu, aka Shaoxing wine (料酒/绍酒), ~5g. Or about 1/2 tbsp.

For the Hot Pot:

Beef stock or your stock of choice, 3 cups or 750ml. Recipe for a Chinese style beef stock is below, though do feel free to use any sort of stock you have on hand. Chicken, pork, whatever (we even used shrimp stock one test, still tasty). A western style stock would be ok so long as you didn’t go crazy on the herb front. You could also simply use water and double up on the chicken bouillon powder.

Salt, 1/4 tsp.

MSG (味精), 1/4 tsp.

Chicken bouillon powder (鸡精), 1/2 tbsp.

Process:

To make the base, first melt the tallow over a medium low flame. Ensuring that the temperature is not too hot - 105 and 110 Centigrade - add in the minced chili bean paste.

Fry the paste on low until it turns into a darker red and it feels a bit “grainy“ when you stir, around ~7-8 minutes.

Add in the ginger, fermented black bean, and rock sugar, fry until the ginger and beans dries up a touch, about ~3 minutes. Add in the chili powder and Sichuan peppercorn, fry together for about ~1 minute.

Add in the laozao fermented rice and Liaojiu aka Shaoxing wine, fry for another minute or so.

For the hot pot:

Transfer the finished base into your hot pot vessel. Add in the stock, bring to a boil, and then add in the remaining seasoning. Taste, and add more salt/chicken powder if needed.

Put the daikon (if using, see the ‘recommended ingredients’ below) in at first since it takes time to cook, then bring to the table and start eating.

How to Make Chinese style Beef Stock:

Ingredients:

Beef bone with marrow (牛骨/带骨髓), sliced open, 1kg

Beef shin (牛腱), 500g

Ginger (姜), a 2-inch knob

Sichuan peppercorn (花椒), 1/4 tsp, optional

Water, 4L

Process:

Add the bone, water, and shin to a pot and bring up to a boil, and down to a simmer. Skim. Add the Sichuan peppercorn and the ginger.

After 90 minutes time, remove the beef shin. You can slice some up for the hot pot if you want, or simply portion and reserve for another use (e.g. turn it into a liangban Chinese style cold salad, or top some noodles, etc).

After a total of six hours of boiling (you can go longer if you like), strain the stock.

Set aside the 3 cups that we’ll be using above, and maybe 1 extra cup for refilling the pot during eating.

Freeze the remainder.

Recommended Ingredients to Add In

Strongly Recommend:

Daikon (白萝卜), 300g. Cut into 5cm*1cm sticks.

Potato (土豆), 1 medium size. Thinly sliced.

Scallion (葱, 小葱), 250g. Cut into 5cm or 1.5 inch sections.

Other Recommendations:

Buffalo tripe (毛肚), 100g-200g per person.

Thinly sliced hot pot beef (牛肉, 肥牛), as much as you want.

Pork brain (猪脑, 脑花), 1 to 2 set.

Beef bone marrow (牛骨髓), a couple pieces.

Spam (午餐肉), as much as you want.

Quail egg (鹌鹑蛋), 6-10 per person.

Tofu puffs (油豆腐), as much as you want.

Konjac jelly (魔芋).

Meat balls (肉丸).

For more ideas, feel free to check out our old Hot Pot 101 video:

Sources and Further Reading:

The recipe itself was adapted from “重庆菜谱” by The Revolutionary Committee of Chongqing Food and Beverage Service Company (重庆市饮食服务公司革命委员会).

Most of the historical bits were based on the writing of Lin Wenyu (林文郁). He wrote a book on Chongqing hot pot (火锅中的重庆) discussing the history and origin of Chongqing hot pot in detail, which is widely cited in other books and academic papers. This article in the Chongqing Morning Post is a very decent summary of that book.

Lin Wenyu extensively cites the work of Li Jieren (李劼人), whose books are a very good source for understanding Sichuan around the first half of 20th century. On a similar note, Chengdu Tonglan (成都通览) by Fu Chongju (傅崇矩) is another good source about the life in (especially Chengdu) around the turn of the century, we actually cited this book in our recent Sweet Water Noodle (甜水面) video.

Unfortunately, the above is only available in Chinese. If anyone has any suggestions on further reading in English on the matter, I’m all ears.

The absolutely gorgeous historical map from the video can be downloaded here in all its 28075 x 13889 glory.

Came here from your YT channel, enjoying your writing! Contains extra flavours

e.g. "Nobody wants to drop acid on a Tuesday"