In the early days of Communist China, a project was commissioned by the Food, Beverage, and Hospitality Bureau of China to catalogue the food around the country. The F&B Industry had recently been nationalized, and so the idea was to go around the country and gather up recipes – in their words, “inherit the traditional cooking wisdom of the working class to better serve the people”.

The end result of the project was a series entitled “The Famous Recipes of China” (中国名菜谱), which was first published in 1958. It’s a pretty amazing document in and of itself – inside of those 11 volumes, there’s an incredible number of mid-century recipes, across 20 different Chinese cuisines.

And inside of volume seven, on page 156, it contains the very first written recipe for Mapo Tofu:

From the looks of it, appears to have been courtesy of Chen Mapo Tofu — the originators of Mapo Tofu, who had long been a Chengdu institution at that point. So as enthusiasts, we figured we’d give it a whirl.

Of course, old recipes can be a little difficult to work with sometimes — tastes change, sensibilities change, and often small intermediary steps are left unspoken. So it often ends up being a game of interpretation: you try to map the recipe against other writing from the time, you try to map it against recipes today. Generally speaking, you shouldn’t charge into a historical recipe completely blind.

But after Steph dug up that recipe, I was excited. Threw caution to the wind a bit, decided to try my hand at it pretty much as it was written, and…

It’s fucking incredible.

The Best Mapo Tofu I’ve ever had

I’ve often pooh-pooh’d the purists online that insist on beef in Mapo Tofu.

Like, we’ve been dragged through the mud before for daring to use pork in the very first Mapo Tofu recipe we shared… and while I’m always pro-high-food-standards, quite frankly I could never understand why people cared so much. Like… we’re all talking about the same Mapo Tofu, right? The fast food lunch dish, the canteen dish? The tofu dish with a million little variations to it, not just internationally but also within China itself? That Mapo Tofu?

It felt to me like one of those foods where the internet had this weird fixation with what’s canonically ‘correct’: Beef in Mapo Tofu, Guanciale in a Carbonara, No Milk with Seafood, Day Old Rice for Fried Rice. The beef fixation always stood in stark contrast with my personal experience with Mapo Tofu in China, where the meat itself was always a sort of tertiary flavor. After all, to my taste buds, the dish was usually either (1) mala as all hell or (2) a delicious, somewhat piquant, fuck-it-slop to top over your canteen rice. Like, who cares?

But now, I get it. I see where it all comes from.

This historical Mapo Tofu is a beef dish:

While I do stand by my previous opinion that there’s no sense obsessing about the protein in a canteen-style Mapo, there is apparently a reason why canon is canon.

I mean, the flavor here is like… halfway there to chili con carne. Everything about the thing is balanced around the flavor of beef — the stock used is a compound beef/pork stock, and the ingredients employed are obviously chosen to go along with beef.

Frankly, it’s a masterpiece. Apologies to any vegetarians in advance.

Ingredients and Sourcing

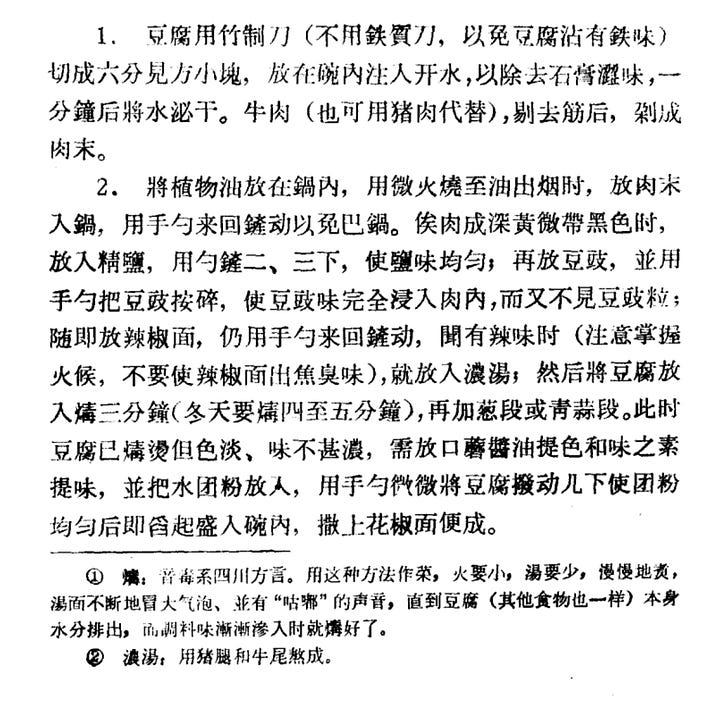

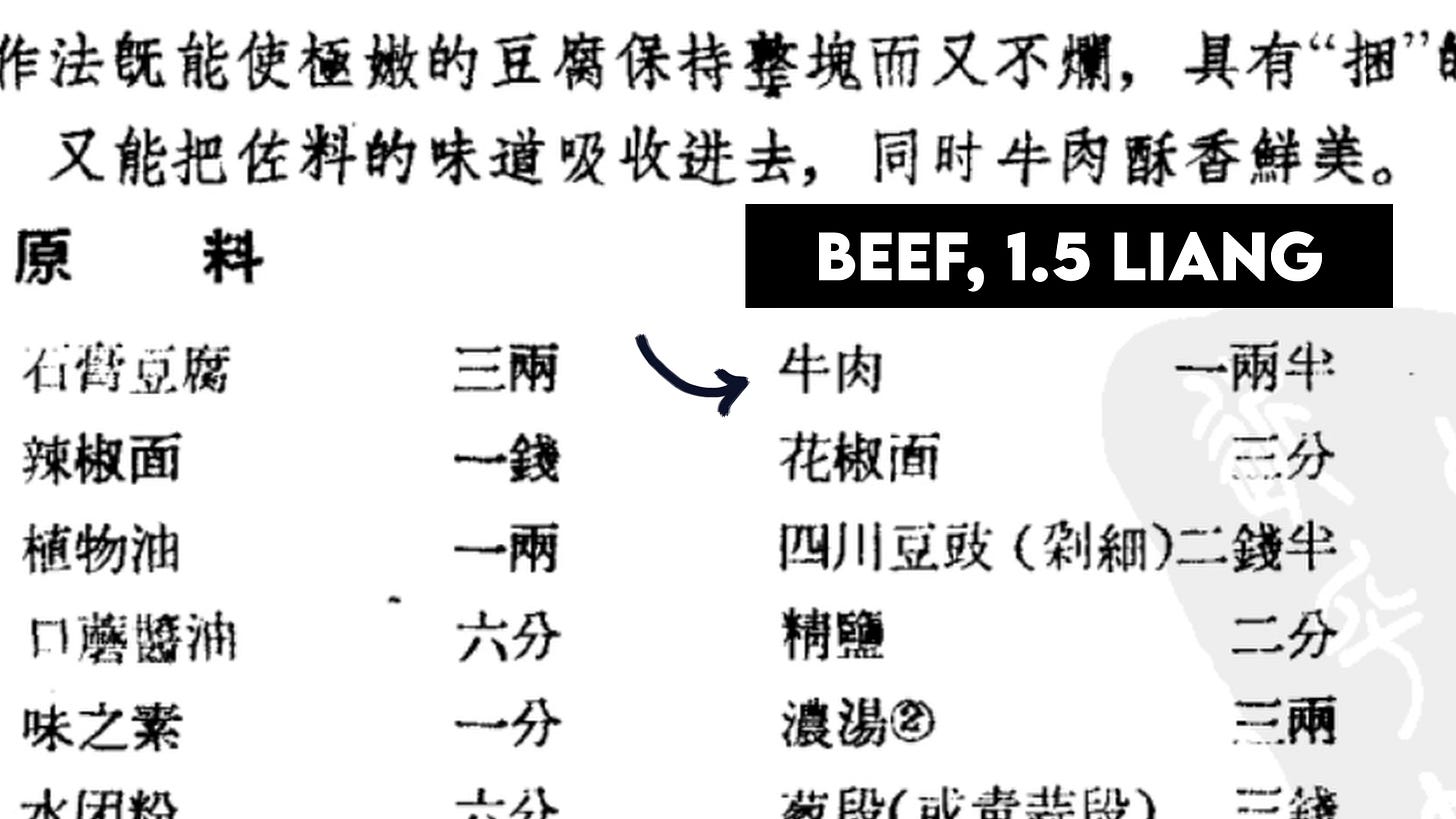

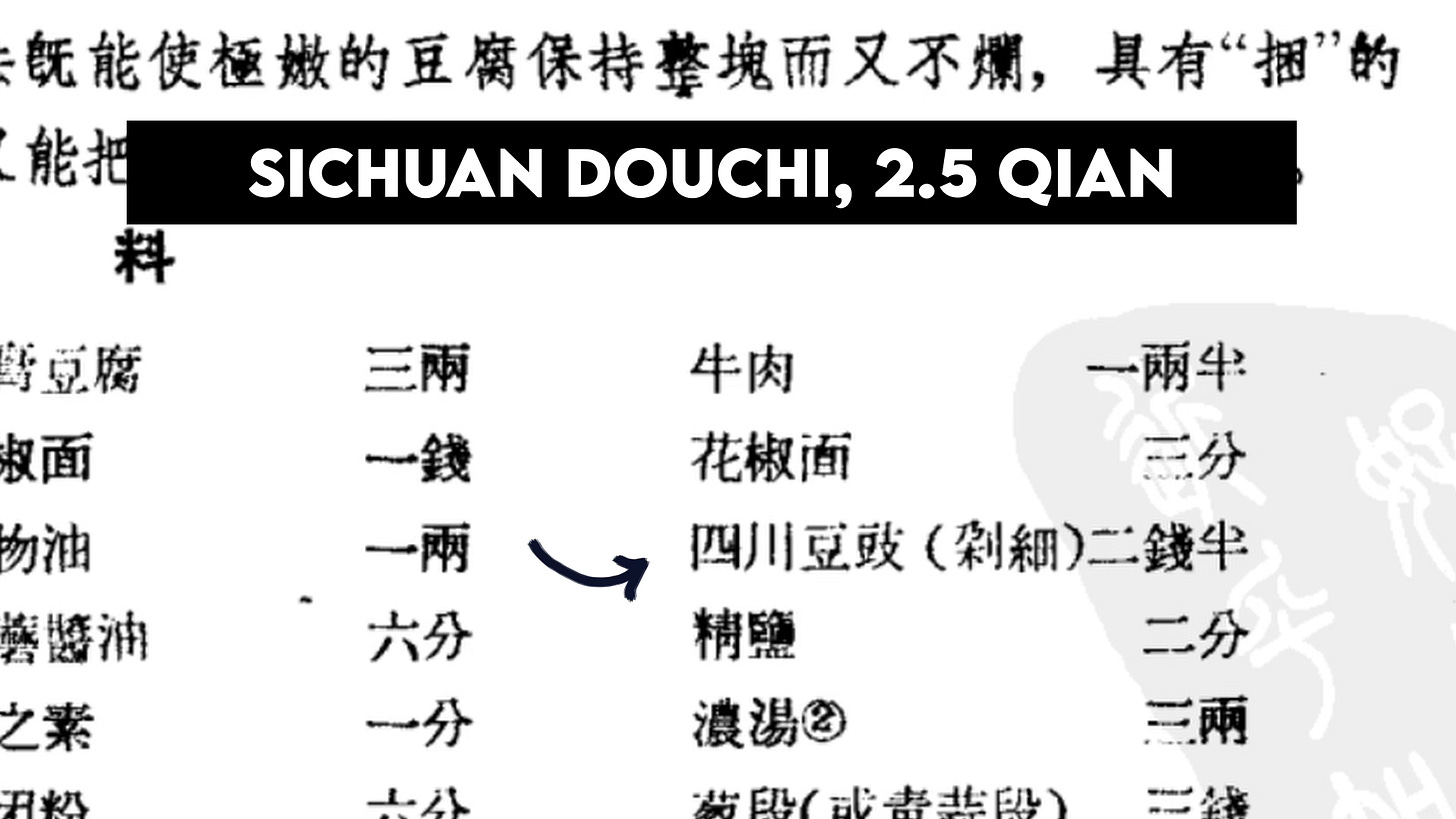

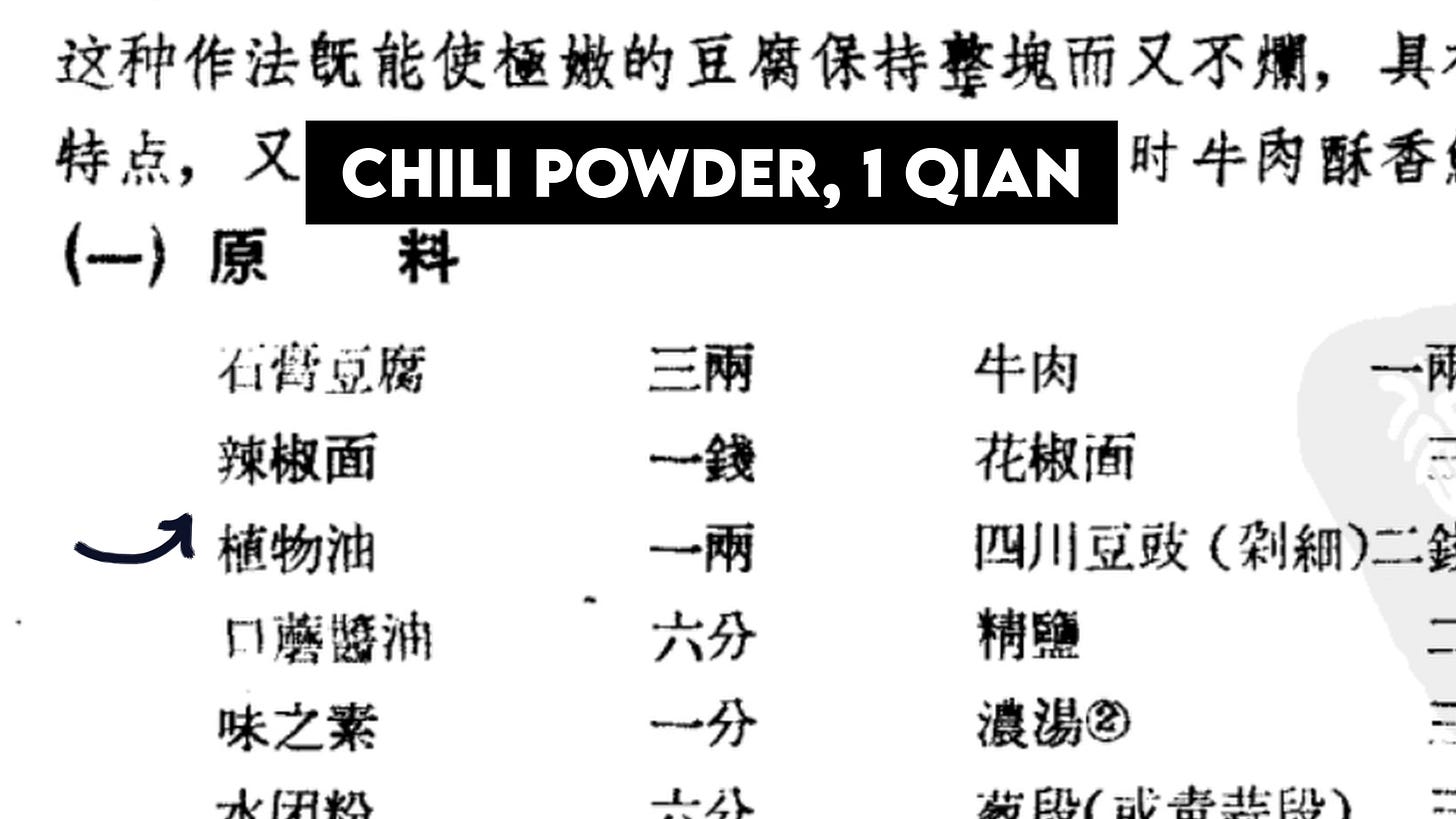

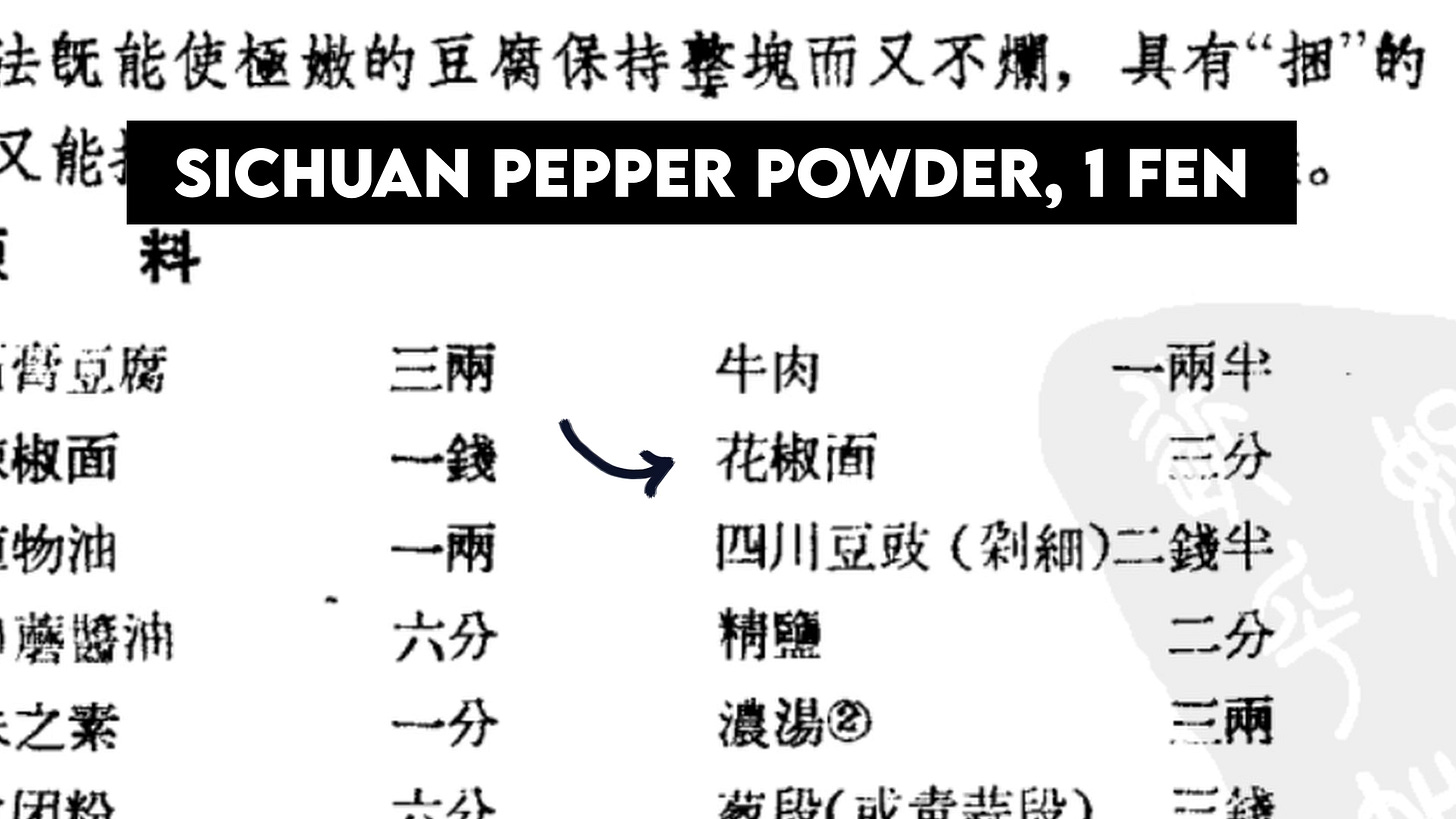

Okay, here’s our direct translation of the recipe itself, if you’re curious and want to follow along:

Either way, let’s break this recipe down bit by bit.

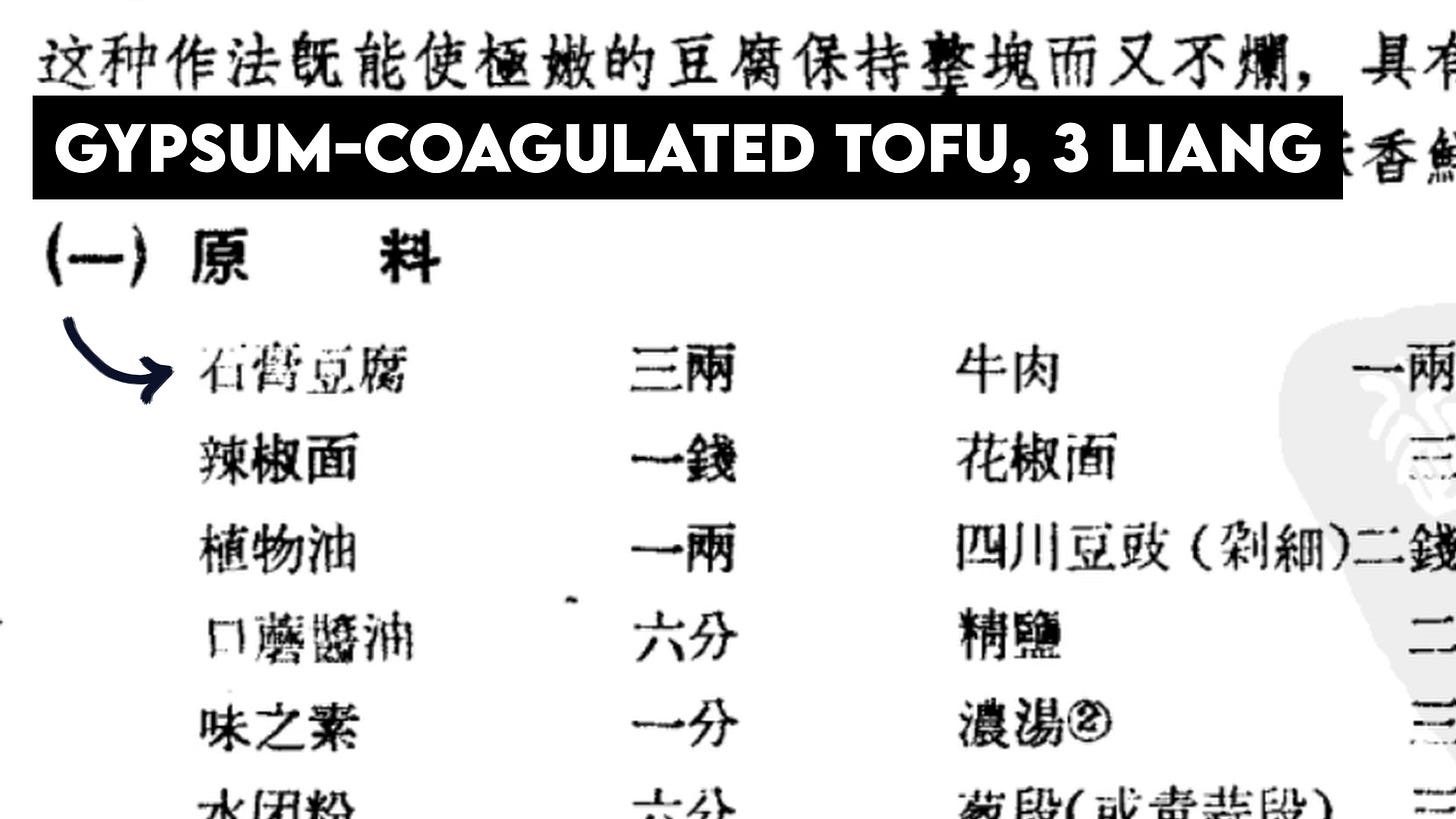

The tofu that the recipe specifies is a gypsum-coagulated tofu – i.e. silken tofu. In China today, often soft tofu (i.e. nigari-coagulated) is used for Mapo Tofu, and would also work here.

The general logic is that the softer the tofu is, the more absorbent it is of various flavors. The introduction describes the in-house-manufactured tofu as ‘especially soft’, so I would personally just use the nicest tofu you can get your hands on. Being Bangkok-based (still), for us this was a Japanese silken tofu.

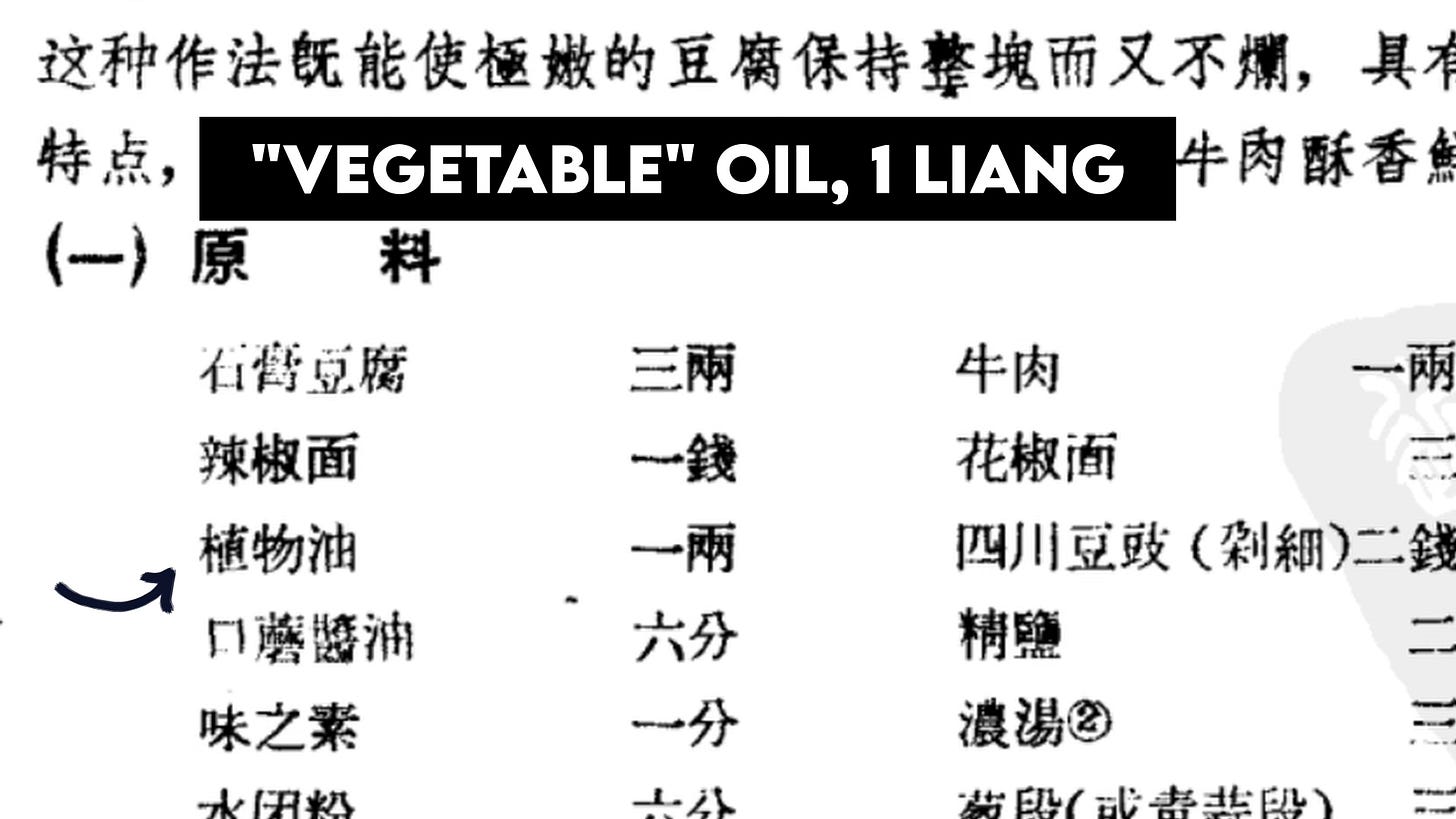

The recipe specifies 1 liang (roughly 50g) of “vegetable oil” — a not-insignificant quantity, corresponding to roughly a quarter of a cup. You might be tempted to cut back on the oil quantity, but try to resist the urge. As stated in the notes of the recipe, the cooking technique here is actually to half fry, half simmer – a move traditionally referred to as ‘du’ in Sichuan.

As to the type of ‘vegetable oil’, this would almost certainly refer to Sichuan’s iconic fragrant rapeseed oil, caiziyou (菜籽油). We’ve introduced the ingredient on the channel before, for the curious. And while I would recommend using some if you can get your hands on it, don’t obsess — peanut, soybean, or canola would all work fine. After all, we’re going to be flavoring the oil with beef, anyhow:

Right. So practically step one of this recipe — and pretty much all canonically correct Sichuanese Mapo Tofus — is slowly frying minced beef in oil until it’s crispy. The point of the addition is less the beef itself, and more so that everything else can fry and simmer in that delicious beef-infused oil.

I’d imagine that is likely why the meat seems to have been cut back on over the years, because this recipe? It pulls… zero punches: 2 parts tofu, 1 part beef. Further, while the recipe itself doesn’t specify too much, other writings on Mapo Tofu from the period discuss the critical importance of using the leanest beef you can find.

Which sounds counter-intuitive: after all, “fat is flavor”, right? If we want beef-infused oil, why not go with the fattiest cut you can, render out all that delicious beefiness? Or, hell, why not go the Chongqing hotpot route and just fry the whole deal in tallow, i.e. pure beef fat?

The answer, I think, actually lies in the previous section — again, this dish does not go easy on the oil. Animal fat is rich, it’s delicious, but it’s also… clingy. Lard and tallow love to grab onto stuff and not let go: perfect for something like a fried rice (and somewhat annoying when you’re washing dishes). But remember — this whole ‘du’ technique employs a non-insignificant amount of oil. The issue with animal fat here is that it’ll cling to your lips and the inside of your mouth, giving the thing sort of ‘greasy’ feeling end result. It’s somewhat subtle, and fine for the first few bites, but by the end of the dish it can get a little much.

So using lean to flavor vegetable oil is honestly a pretty genius move — you get the flavor of the beef, without that ‘greasy’ sensation. At the same time though, that also leads us to another problem, which is… the issue of beef quality.

You see, whenever you’re working with historical recipes, it’s critical to remember that meat in the past used to be much more flavorful than it is today. All chickens were ‘free range’, all beef was ‘farm beef’. Go to countries today that keep a more traditional food supply chain, and you can see the difference rather plainly1.

Often when I work with historical recipes, I square that knot with fattier cuts. Here, that’s an issue. After trying a few different choices, I ended up settling on beef shin. Yes, that’s a stewing cut, but after mincing and frying the texture will work out just fine. In the accompanying video we hand minced the beef, but for this application there’s no reason not to grind it (we don’t own a grinder).

I didn’t test this recipe at all with pre-ground beef. If you can’t sort the shin, I would opt for the leanest, fanciest, grass-fed beef that you could find (the shin route would probably be cheaper?).

In the accompanying video, we discuss at length one of the most surprising aspects of not just this historical recipe for Mapo Tofu, but pretty much all of them: before the mid 20th century, Sichuan Mapo Tofu apparently did not use Pixian Doubanjiang, Sichuan Chili Bean paste.

Instead, they use douchi, Chinese fermented black soybeans. Douchi have a sort of chocolate-y richness that simply goes fantastic with beef… and honestly? I think I prefer it here.

In the recipe, they specifically call for a Sichuan Douchi. For the obsessive, these are actually available on Mala Market. Our Sichuan douchi were beginning to run out about halfway through testing, so I also began to make batches with Cantonese Yangjiang douchi (i.e., a bag like this). For this specific dish, I felt either work great.

For the chili powder, you’ll have a good bit of flexibility. But because there’s zero chili bean paste, the one thing that you do not want to do is try to lean on that three year old bottle of cayenne pepper at the back of your spice cabinet.

I ground my own using a mix of chilis, but if you have a chili powder that you’re comfortable with… go for it. In the United States, I find that Korean Gochugaru’s reasonably high quality — if you’re someone with a low spice tolerance and gochugaru registers as “spicy” for you… I think you could likely use it straight up (it’s got a decent fragrance and some fantastic color). For my taste buds, gochugaru registers as “quite mild”, so I need to go a different route.

Being Bangkok-based (still), I used a mix of 2 parts Sichuan erjingtiao chilis and 1 part Korean chilis, with a few Sichuan xiaomila thrown in for heat — all lightly toasted, then ground up. But definitely do use what’s local and makes sense for you: if I was in the USA, I might try a mix of 3 parts Guajillo chilis and 1 part Tientsin chilis.

Lastly, after testing the recipe, I found that I enjoyed the dish most upping the chili powder quantity by 50% (perhaps due to the Korean chili). In the recipe below, I decided to roll with the increased quantity. Up to you.

For the Sichuan Pepper Powder, we’re happy with the pre-ground powder that we buy, so we used it straight up. Sometimes there’s a bit of variability in exported Sichuan pepper powder, so grinding your own is certainly an option too.

Note that unlike our previous Mapo Tofu recipes, we aren’t toasting the peppercorns in this one. This will be much less numbing than our previous recipe.

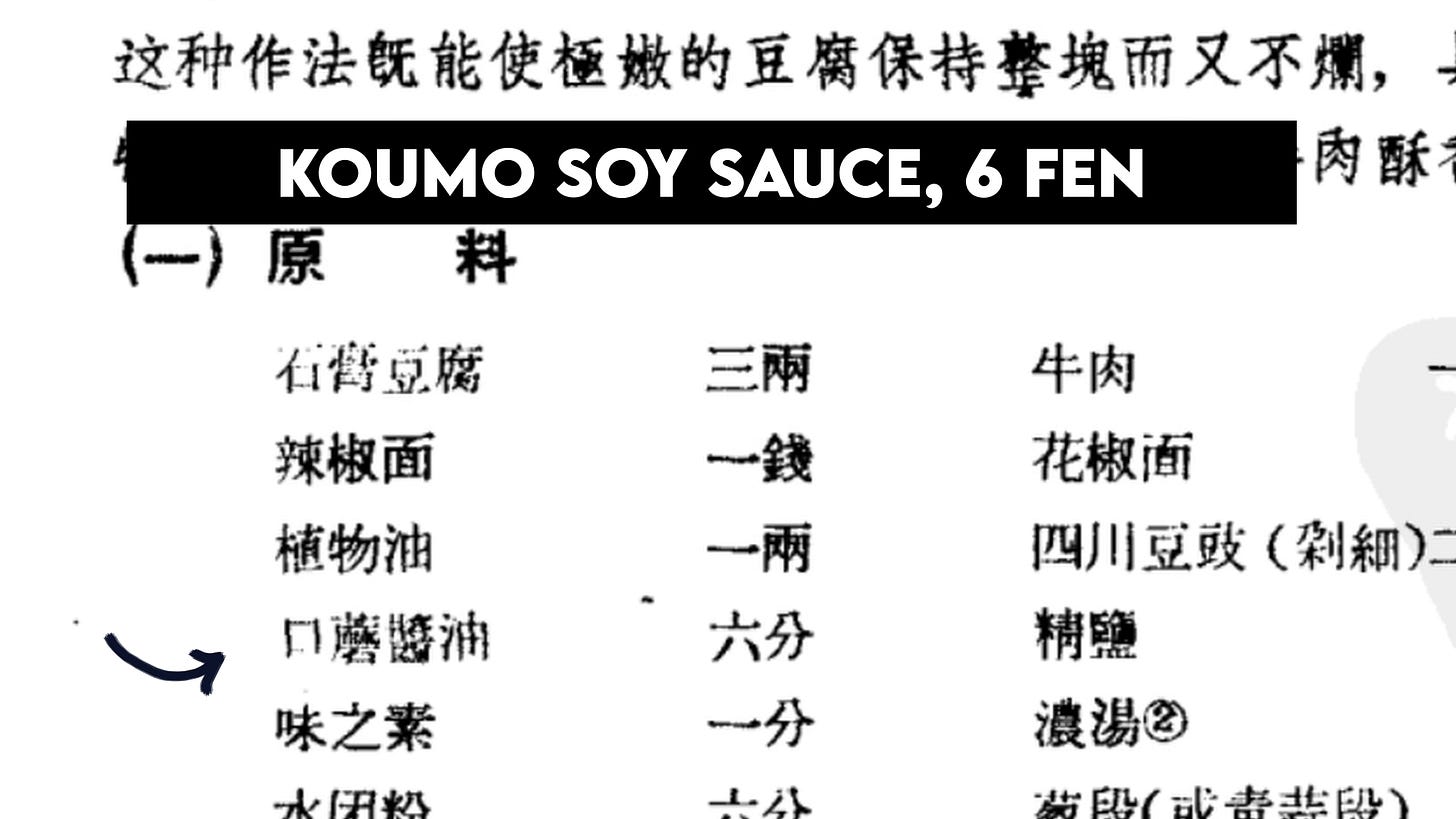

The soy sauce that they specify is a Sichuan type of soy sauce called koumo soy sauce – this soy sauce uniquely ferments soybeans together with mushrooms, giving it its name. For the obsessive, again, the product is actually available on Mala Market here, but any decent Chinese soy sauce would work.

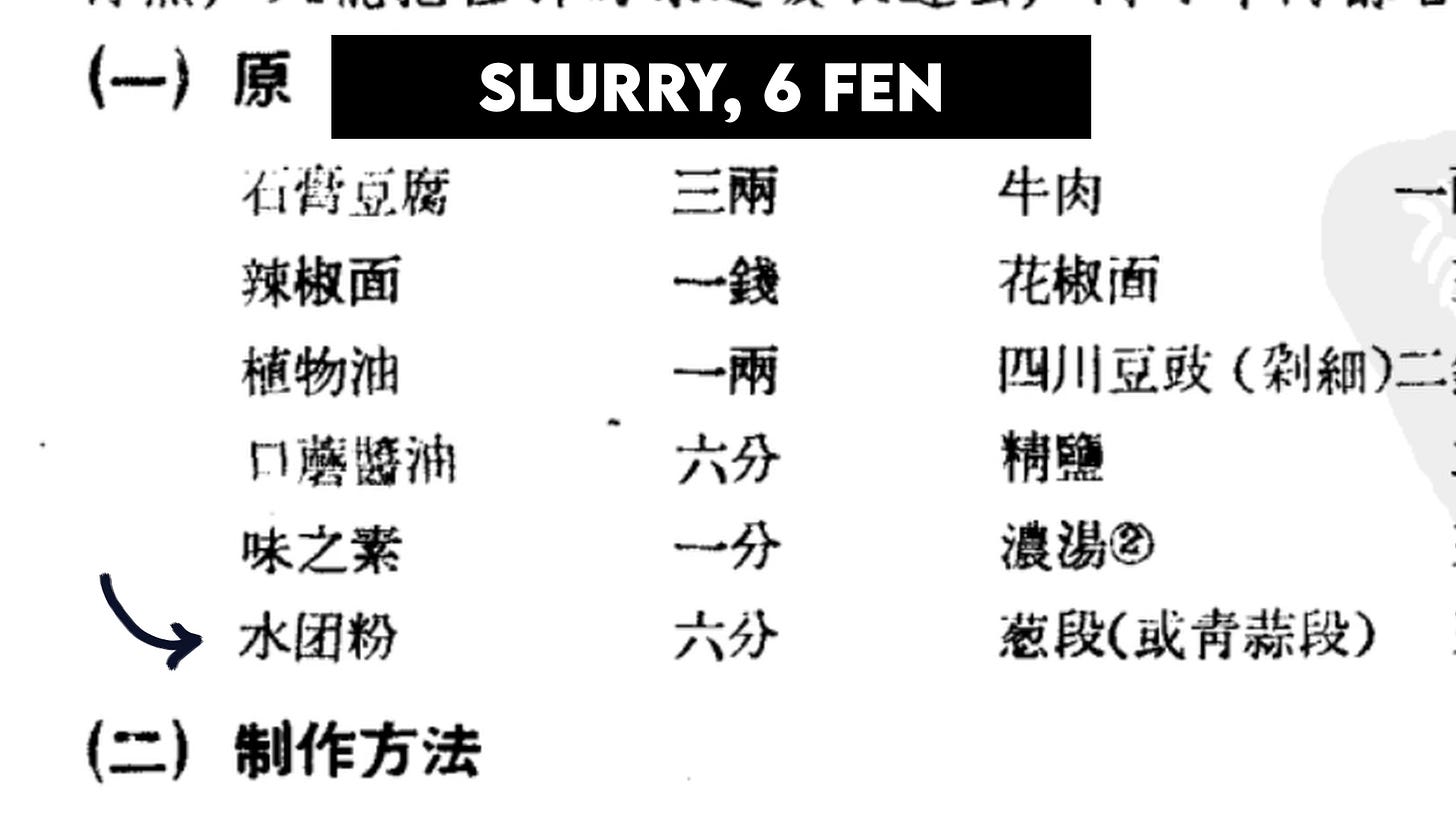

The slurry quantity is somewhat ambiguous. Presumably, if they call for 6g of ‘slurry’, this should equate to something like 3-4g of dried starch. After a couple batches, I found that working from 6g of starch got me to the thickness that I wanted.

For this type of dish, it’s best if you can use a root vegetable starch like potato, sweet potato, or tapioca starch if at all possible (the sauce will hold better than if using cornstarch).

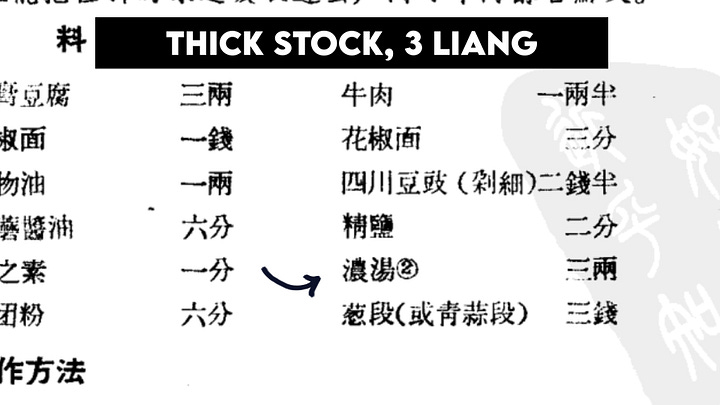

Lastly, they call for a ‘thick stock’2, i.e. a meat-heavy stock. In the notes, they discuss that the stock used is specifically a compound stock made from oxtail and pork trotters.

For ease of international replication, we used a mix of beef shin (as we’re already using it in the recipe) and pork bones for soup (which should be available at pretty much any Asian supermarket. If you’re following this recipe, I heavily recommend making some stock beforehand — it adds a ton of complexity..

We also chose to double the recipe, so this will be our final ingredient list:

For the compound stock (this will make more than you need; also, refer to the note below for how to use the extra meat):

Beef shin (牛腱), 500g

Pork bones for soup (猪骨), 500g

Ginger, ~1 inch, smashed

Scallion, ~1 sprig

Liaojiu a.k.a. Shaoxing wine (料酒/绍酒), ~1 tbsp

Sichuan peppercorns (花椒粒), ~7-8. Optional.

Water, 3L

Beef shin (牛腱), 150g. Ground or hand-minced.

Silken tofu (嫩豆腐), 300g. Or, alternatively, soft tofu.

Chili powder (辣椒面), 15g. I ground mine using a mix of chilis. Use what would get this to ‘medium’ spicy for you.

Sichuan pepper powder (花椒面), 1 tsp.

Oil, preferably Chinese rapeseed oil (菜籽油), ½ cup.

Douchi, i.e. Chinese fermented black soybeans (豆豉), 25g.

Soy sauce (生抽), 1 tsp.

Salt, ⅜ tsp.

MSG (味精), ¼ tsp.

Compound stock from above, 300mL

Scallion, 30g. Cut into ~1.5 inch sections.

Slurry of 2 tsp starch mixed with 2 tsp water. Preferably potato, sweet potato, or tapioca starch.

Recipe

To a pot of cool water, add:

500g beef shin

500g pork bones

and bring up to a boil. Boil for three minutes, then drain. Rinse the meat with cool water, then add in:

3L Water

~1 inch smashed ginger

~1 sprig scallion, tied in a knot

1 tbsp Shaoxing wine

Optional 7-8 Sichuan peppercorns

Bring up to a boil and down to a simmer, skimming if you need. Simmer for 4-5 hours.

Remove the meat and reserve for another use (don’t toss it). Strain the stock, we’ll need 300mL today.

Mince:

25g douchi, Chinese fermented black soybeans

Cut into ~1.5 inch sections:

30g scallion

Grind or hand-mince:

150g beef shin

Prepare a slurry of:

2 tsp starch mixed with 2 tsp water

Cut into ~1 inch cubes:

300g silken or soft tofu

then place in a bowl. Pour in hot, boiled water from the kettle and let steep for 1-2 minutes. Drain the water.

Heat up a wok over a high flame, then add in:

½ cup oil

Once it’s hot enough where bubbles can just form around a pair of chopsticks, swap the flame to medium and add in the beef. Fry the beef until it’s past done, slightly golden, and the oil begins to clear up once again, 6-7 minutes. Then add:

⅜ tsp salt

and quickly mix. Then add the minced douchi. Fry by really smushing the douchi into the beef, combining as evenly as you can, ~45-60 seconds. Then add:

15g chili powder

and fry until fragrant, ~15 seconds.

Add the stock and up the flame to medium-high. Once simmering, add the tofu. Cover with a loose fitting lid (or with the lid ajar). Cook for 3-5 minutes. You will be looking for the liquid to have reduced by roughly a quarter.

Add the scallions, then season with:

1 tsp soy sauce

¼ tsp MSG

and mix. Add in the starch slurry, thickening to your liking. Add:

1 tsp Sichuan pepper powder, or to taste

I like adding half, and adding the rest at the table.

How to Use Up the ‘Stock Meat’

Unlike western stocks which tend to lean on scraps, Chinese stocks will often have meat inside. This meat will, of course, be repurposed — it’ll be less flavorful, of course, but it’s still good for many applications.

An obvious choice for the beef shin would be to cool it down and dry it out, then thinly slice it. You can take a look at how to do this inside of our ‘how to Danshan-ify everything’ post. Unlike the linked recipe, the shin will obviously lose a good bit more flavor over the course of 4-5 hours… but it’ll still be delicious devoured with chili oil.

Another thing you can do with the stock meat is what we showed in the video: a Yunnan-inspired ‘beef soup pot’. Thinly slice the beef and make the oil-based Danshan dip (ala the linked recipe above). Then make a pot with one part stock and three parts water — boil this with tomato, scallion or green garlic, ginger, and celery, and season with salt and MSG. Eat everything as a hotpot. Mint is one go-to vegetable for this sort of pot.

A more direct application, however, would be something like Hunan’s Chaigurou Hebaodan (拆骨肉荷包蛋), which we showed in this video:

All that said, I mean, it’s… meat. You’ll find a way to use it. You can literally just take the stuff and dip it in a nice soy sauce as a snack. Or you could toss it as a random noodle soup topping, ala our Noodle Soup 101 post (e.g. Steph’s been putting some in her fuck-it-lunch-soup as of late). Can’t figure out a way to use it immediately? Shred it, portion it out into little one serving baggies, and freeze it — it can be added to fuck-it-soups direct from frozen, no need to thaw.

As an aside, I always find it amusing when expatriates in Asia complain about the ‘skinny, tough’ meat that you can find in this corner of the world. I’ve heard Americans dismiss chicken in China as “Auschwitz chicken”; beef in rural Thailand as meat from “anorexic cows” — people are apparently so used to roided-up, penned-in animals that they begin to take it as a point of cultural pride.

Of course, I don’t mean to be a food snob, nor am I an animal right activist. Cheap protein has been a wonder for the modern world, and I also know that not everyone can shell out the cash for fancy farm meat on the regular. I just sometimes can’t help but find it amusing when people literally complain about quality meat, as it’s just so alien to them.

A more direct translation would be ‘concentrated stock’, but I don’t want to confuse it for a product like stock concentrate or demi-glace. Basically, this refers to a stock made using a non-insignificant quantity of meat.

1958?! That recently?

I love mapo toufu, too bad that I had to reduce spicy food to almost 0 to avoid raising Yangqi.