I was sitting at the bar with my old (now ex-chef) friend Adam, telling him about our plans for this video. He looked confused:

“Uh… how exactly are you defining ‘curry’?”

I sort of shrugged and shot the question right back at him. His answer was something along the lines of ‘a stew that begins with pounded spices and aromatics’.

It’s… a definition that I think much of the food world would likely agree with. And if we grade using that rubric, ‘curry’ certainly isn’t ‘western’ – like, there are even archeological remains from the Indus valley that suggest this broad approach was used literally before… ‘the west’ was a thing.

But sort of like the now-beaten-to-death is a hot dog a sandwich debate, this sort of definitional specificity can quickly lead to silliness like… ‘a mole is a curry’ or ‘a Japanese curry is not a curry’. The word’s also an exonym – after all, Indians historically didn’t call their own curries ‘curries’ (though the situation is more complicated today). Instead, it was a term was coined by Europeans to (clumsily) refer to a wide swath of stews consumed in places as culturally disparate as Afghanistan and Thailand.

Let’s try to see this from the other side. The term for “Hot Dog” in Mandarin is “热狗包”, or literally hot (热) dog (狗) bao (包). So… is a hot dog a Baozi?

Definitely not! Hot dogs are an American food. If you have any doubt, try swinging up to a hot dog vendor in Manhattan and telling them “two Baozis please”. Similarly, I think curry is something that the people in said culture refer to as a curry. In practice, these curries usually lean on a product called ‘curry powder’ (or something similar) as a base flavor.

Adam thought for a second. He was unconvinced, but did grant:

“…I guess that would make it pretty western.”

The British Invention of Curry Powder

The story begins with the Anglo-Indians.

While ‘Anglo Indian’ means something a bit different today (generally referring to mixed race British/Indian), historically the term was used to describe the the British that lived long term in colonial India. Over the centuries of colonial rule - and particularly during the reign of the East Indian Company - this group began to develop their own distinctive cuisine, adapting local dishes to their palate: Khichri morphed into Kedergee, the peppery Rasam became Mulligatawny, and Chatni became Chutney. Similarly, in the Anglo-Indian culinary world, ‘Curry’ was a dish in and of itself. As explained by historian Lizzie Collingham in her (excellent) book Curry: A Tale of Cooks and Conquerers:

British ‘curries’ in India used a basic formula: first spices, onions and garlic were ground and bound together by ghee, then this paste was added to some meat, and simmered.

When these ‘curries’ made the trip back to England however, there was an important alteration, as Collingham describes:

…in Britain a similar recipe was followed. Onions and meat were first fried in butter, then curry powder was added, followed by stock or milk, and the mixture was left to simmer. Just before serving, a dash of lemon juice was added. […] What distinguished curries in Britain from their Anglo-Indian counterparts was their reliance on curry powder.

Of course, how this thing called ‘curry powder’ came about is… incredibly murky. Most seem to agree it was a British concoction (or, alternatively an invention by Indian spice merchants selling to the Brits) meant to replicate the… vibe of an Indian masala, and seems to have hit the scene sometime in the 18th century.

The venerable Madhur Jaffrey jokes in An Invitation to Indian Cooking that she images the origin story a bit like this:

But from its cloudy origin, that bottled curry powder spread to… practically the four corners of the globe. Where the Brits went, curry powder wasn’t far behind, leaving a trail of localized variants of that original Anglo-Indian theme. You could find curries popping up everywhere from the United States, to South Africa, to Nigeria, to Guyana, to Jamaica, etc etc:

It was, perhaps, the first truly global dish.

Curry in Guangdong

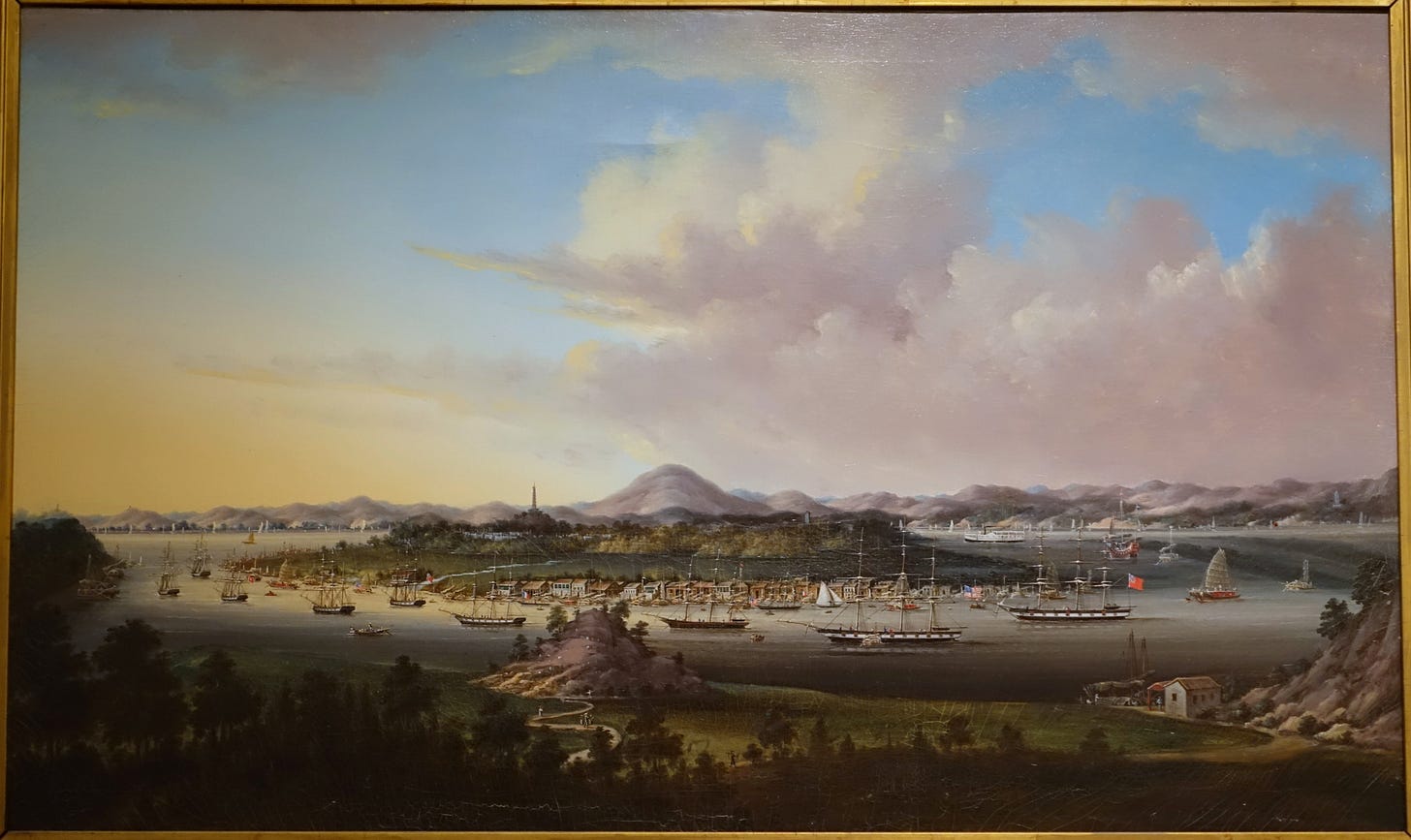

The earliest mention of Curry that we could personally find in Guangdong was via a dish called Country Captain, a renowned Anglo-Indian chicken curry that was, for one reason or another, a particular favorite for travelers on the move. In his book The Fan Kwae at Canton, William C Hunter - a native of Kentucky that was among earliest batch of Americans to reside in Guangdong - discusses eating the dish at the anchorage at Whampoa:

The local name for their business [the India-China trade] was the 'Country Trade' the ships were 'Country Ships' and the masters of them 'Country Captains.' Some of my readers may recall a dish which was often placed before us, when dining on board these vessels at Whampoa, viz., 'Country Captain.'

Hunter’s etymology there may or may not be a bit suspect (the aforementioned Collingham lists a few alternative theories in her book that seem a touch more convincing), but what seems clear is that following the pathways of the India-China trade, curry followed the Brits along for the ride.

So in neighboring Hong Kong, in the early days, the dish was more or less synonymous with the Imperial Brits and the Ghurkas they employed. But from there it began to spread down into the police force, where you can still find it in canteens today.

And yet, as the 20th century wore on, Curry found a new home: Cantonese Cha Chaan Teng. These are restaurants that, in essence, tried to bring the heretofore luxuriously expensive western food down into the budgets of ordinary Hong Kongers. In the process, western dishes were adapted to both Cantonese tastes and the ingredients that were (cheaply) available… forming a sort of Canto-western Fusion in the process.

And so it’s no real surprise that curry found its way onto Cha Chaan Teng menus. What is a touch surprising though, I think, is that the Cha Chaan Teng curries seem to borrow a lot of sensibilities from Hong Kong’s sister colony of Singapore: spices are employed in paste form, you can find aromatics like shallot and lemongrass in more than a few curry bases, and quite often the curry is finished with either evaporated milk or… coconut milk.

Recipe: Hong Kong Chicken Curry (咖喱鸡)

Ingredients:

Chicken, ~300g. Cut into ~1.5 inch chunks. We used a combination of two deboned thighs and one full wing, cleaved up.

Potatoes, preferably fingerling, 250g. Sliced in half, then cut into ~1.5 inch chunks via the Chinese rolling cut.

Salt, 1/2 tbsp. To boil the potatoes.

To marinate the chicken:

For the marinade:

Salt, 1/4 tsp

Sugar, 1/4 tsp

Chicken bouillon powder (鸡精), 1/4 tsp

Curry powder (咖喱粉), 1/2 tsp

Soy sauce (生抽), 1/4 tsp

Liaojiu a.k.a. Shaoxing wine (料酒/绍酒), 1/2 tsp

Cornstarch (生粉), 1 tsp

Onion, ~1/4. Cut into chunks.

Ginger, ~1 inch. Smashed.

Optional: dried bay leaf (香叶), 1. If you have it around.

Peanut oil, ~1 tbsp. To coat.

For the curry base:

Onion, ~3/4. Finely, finely minced.

Garlic, 3 cloves. Finely, finely minced.

Hong Kong Curry Paste (咖喱胆), 2 tbsp. This is what we used in the video. If you can’t find it, a Singaporean/Malaysian style curry paste like this could also be used, or perhaps in a pinch a good Thai Yellow Curry paste. You can also make it yourself - we have a recipe in an old video.

Curry powder (咖喱粉), 1 tsp.

Water, 1 cup.

Chicken bouillon powder (鸡精), 1/2 tsp.

Mashed potato. ~1 chunk worth from the above potatoes.

For the stir fry:

Liaojiu a.k.a. Shaoxing wine (料酒/绍酒), 1 tbsp

Curry base from above.

Soy sauce (生抽), 1 tsp

Water, 1 cup

Seasoning:

Salt, 1/4 tsp

Chicken bouillon powder (鸡精), 1/4 tsp

MSG (味精), 1/4 tsp

Sugar, 1 tsp

Evaporated milk (淡奶), 1.5 tbsp

Coconut milk (椰奶), 0.5 tbsp. You can alternatively finish with 2 tbsp of evaporated milk or coconut milk if you don’t happen to have both already on hand.

Process:

Prepare the chicken and mix it with the ingredients listed under “to marinate the chicken”. Marinate for at least 30 minutes, or up to overnight.

Slice the potatoes, then boil them in water salted with 1/2 tbsp salt. Boil for ~10 minutes until soft. Reserve, mashing one of the potato chunks up for the curry base.

In a pot, fry the minced onion in with ~1.5 tbsp of oil over a medium flame. Once slightly softened, ~3 minutes, add in the minced garlic and fry until fragrant. Add the curry paste and curry powder, and fry until those are fragrant as well, ~30 seconds. Add the water, the chicken bouillon powder, and the mashed potato. Boil uncovered until the water has evaporated and everything as bubbled down into a gloopy paste, ~40 minutes. Reserve.

To stir fry, first longyau: get your wok piping hot, shut off the heat, add in ~1.5 tbsp of oil, and swirl to get a non-stick surface. Over a high flame, add in the chicken together with the marinade. Spread it evenly across the wok, then stir fry for ~90 seconds, or until cooked. Swirl in the wine, mix, then add the curry base. Mix again and swirl in the soy sauce. Add the water, and swap the flame to medium.

Boil the curry for ~10 minutes, then add the potatoes. Boil for another 5 minutes.

If the curry is not quite thick to your liking, you can reduce on high for 1-2 minutes. Finish with the seasoning, the evaporated milk, and the coconut milk.

Serve with rice.

Curry in Japan

Curry likely first hit Japan during the Meiji era via British traders in Yokohama, though some do argue that it was via foreigners employed in Hokkaido. Whatever the case, the first curry recipes in Japan all seemed to use - besides the requisite curry powder - flour to thicken the stew.

You can see the approach in the very first recipe for curry to hit the Japanese language, via a book entitled “A Guide to Western Cooking”:

The method of making curry is to take one stalk of green onion, half a piece of ginger, a little bit of garlic, and finely ground them. Boil them in one large spoonful of cow milk, then add one and a half cups of water. Add chicken, shrimp, sea bream, clams, frogs, etc., and boil well.

After that, add one small spoonful of curry powder and boil for one hour. When it is fully cooked, add salt. Also, dissolve two tablespoons of flour in the water and mix well.

It’s a move pretty obviously borrowed from the Brits, who would similarly thicken their curries with a roux - particularly historically, though you do also see flour employed in chip shop style curry sauces today as well. In the Meiji era, a common technique became to first toast flour, then mix it with curry powder, and then slowly mix in stock to get a curry base. Here you can get a sense of what a homemade curry roux would look like (although the creator here binds the flour with oil before adding the powder):

Post war however, that song and dance was streamlined with pre-packaged, ready-made instant curry roux. It was first developed by a company called Oriental in 1945, although today by far the most famous purveyor is S&B and the “golden curry” brand.

And the product became a homecooking mainstay in Japan for a pretty obvious reason: it’s tasty, and… absurdly dead simple to use. Like, honestly, you pretty much don’t even need a recipe - you can just follow the box with quite satisfying results.

That said, being a cooking channel, we probably have to give you something a little more in depth than “just follow the box”, so:

Recipe: Japanese ‘Naval Curry’-Inspired Curry (海軍カレー, -ish)

One of the the more interesting curry-related tales was how, near the turn of the 20th century, curry rice began to become standard ration in the Japanese navy. It’s an interesting story in its own right, well covered by this article in Atlas Obscura for the curious. The TL;DR is that curry helped counteract Beriberi (Thiamine deficiency), although getting curry on to these naval vessels was… its own drama.

This gave rise to its own style of curry called “Navy Curry” (海軍カレー) or “Yokosuka Navy Curry” (よこすか海軍カレー). And of course, being Japan, Yokosuka Navy Curry obviously also has its own mascot (to the right):

One of the pleasures of delving into Japanese dishes in these ‘Western food in Asia’ videos is that there’s just… so much information out there. The history is easy to research, the recipes are easy to find. So even though we don’t know Japanese (though Steph can read a bit due to the combination of knowing Chinese characters/Kanji and a bit of study in university), it’s not too difficult to find good sources.

Like, the Japanese ministry of defence even has a list of curry recipes. Really making our job easy. So for this curry, we delved into those recipes a bit, cross referencing it with this video over on YouTube:

We did, however, want to use the boxed curry roux, as it’s such a modern classic in Japan today. So the following is a blend of that Yokosuka Naval Curry from the video above adapted with a bit more of a homecooking style.

Ingredients:

Beef Brisket, 175g. Cut into ~1 inch chunks.

Carrot, 75g. Halved, then cut into ~1/2 cm slices.

Potatoes, preferably fingerling, 100g. Quartered, then cut into ~1cm chunks.

For the onion base:

Onion, 1/2. Finely finely sliced.

Salt, 1/4 tsp.

Oil, 1 tbsp.

Water, 1 cup.

For the curry:

Butter, 2 tbsp. For frying.

Garlic, 2 cloves. Grated (or pounded).

Ginger, ~1 cm. Grated (or pounded).

Onion base from above.

Ketchup, 1 tbsp.

Worcestershire sauce, 1 tsp.

Water, 2 cups.

Chicken bouillon powder, 1/2 tsp.

Optional: the juice from Japanese Fukujinzuke pickles, 1 tbsp

Apple, 20g. Grated.

Curry roux, 2 chunks. Or a half pack.

Seasoning:

Salt, 1/4 tsp

MSG, 1/4 tsp

Sugar, 1/2 tsp

Butter, 1/2 tbsp. For finishing

For the curry oil:

Oil, 1 tbsp

Curry powder, 1/2 tbsp.

Process:

Prepare the beef, the carrot, and the potato and set aside. Thinly (keyword: THINLY) slice the onion.

To make the onion base, first add the onion together with the salt and oil in a non-stick. Over a medium low flame, fry until it begins to soften, ~5 minutes. Add the one cup of water. Cook over a medium flame until the water reduces away and the onion is so soft that it’s practically disintegrating, ~15-20 minutes. Reserve.

To make the curry, first fry the beef in the butter over a medium-high flame. Once browned, 2-3 minutes, add in the carrot and fry for ~1 minute. Add the potatoes, fry for ~1 minute. Add the grated garlic and ginger and fry until fragrant, ~30 seconds. Add the onion base, the ketchup, and the worcestershire sauce, and briefly fry together.

Add the water, the chicken bouillon powder, the grated apple, and the optional pickle juice. Cook until the beef is soft, 30-40 minutes.

Add the curry roux, letting it melt and thicken the curry. Once thick to your liking, add the seasoning. Finish with butter and curry oil.

To make the curry oil, heat the oil up until it can barely begin to bubble around a pair of chopsticks, ~120C. Add the curry powder and mix, making sure that the curry powder does not burn.

To serve:

For the full naval rations effect, serve the curry with rice, Fukujinzuke pickles, a side salad (I used a boxed Japanese style salad from Kewpie in the video), and a juice box of milk.

Curry in Thailand

Most of what people consider “Thai curry” is - by our definition - not exactly “curry”. It’s kaeng.

Green curry? Kaeng Khiao Wan (แกงเขียวหวาน)

Red curry? Kaeng Phet (แกงเผ็ด)

Massaman curry? Kaeng Matsaman (แกงมัสมั่น).

“So what?” you might say. “Curry is just the English translation for ‘Kaeng’, just like Stir Fry is the English translation of ‘Chao’”.

Which… fair enough. It’s the common translation, no need to swim upstream. But call it what you will, I don’t think we can categorize ‘Kaeng’ as ‘Curry’, even using the broad definition employed by Michelin and my buddy Adam in the intro.

After all, there’s stuff like Kaeng Jeut, or ‘Plain’ Kaeng:

If we were starting from scratch, I’d personally be partial to translating kaeng as ‘soup’. After all, etymologically the word shares a lineage with the Chinese character “羹”, pronounced in middle Chinese as… drumroll… ‘kaeng’. In modern Cantonese, this is pronounced ‘gang’ (Mandarin, ‘geng’), and is pretty universally translated as soup:

The absurdity of Kaeng being classified as ‘curry’ really begins to hit home when you take a look at the dish “Yellow Curry”. In Thai, it’s called Kaeng Kari (แกงกะรี่), or sometimes Kaeng Kari Thai. It’s a dish that hails from the south of Thailand, and is often synonymous with the Muslim Thai food in that region.

And perhaps predictably, our Kaeng Kari uses Phong Kari - curry powder - as a base flavor. This is the dish that I would label as a ‘Thai Curry’.

But unlike curry in Hong Kong and Japan, Kaeng Kari definitely isn’t categorized as ‘western food’. There’s also plenty of people out there more qualified to cover the dish than we are.

Instead, we wanted to cover another curry powder-based dish called “Curry Powder Fried Seafood”. It’s descended from a dish called “Curry Powder Fried Crab”, that seems to have been a riff off of Singaporean Crab curry - a dish itself believed to have been descended from… Goan Portugese Caril de caranguejo.

Okay, it’s a stretch. And it’s still definitely not categorized as ‘Western food’ in Thailand: it’s squarely thought of as Thai, or maybe Thai-Chinese if you really pressed. We’re covering this dish mostly because… we want to, as it’s probably the quickest way humanly possible to arrive at a ‘curry’.

Recipe: Thai Curry Powder Fried Seafood (ทะเลผัดผงกะหรี่)

Ingredients:

Squid, ~2 small.

Shrimp, 5-6 medium.

Marinade for the Shrimp:

Salt, 1/4 tsp

White pepper, 1/4 tsp

Cornstarch, 1/2 tsp

To make the sauce:

Evaporated milk, 50mL

Water, 50mL

Nam Phrik Phao (น้ำพริกเผา), Thai chili jam, 1.5 tbsp. This stuff, should be pretty available internationally.

Egg, 1

Oyster sauce, 3/4 tsp

Salt, 1/8 tsp

Chicken bouillon, 1/4 tsp

Shaoxing wine, 1/4 tsp. Optional.

Fish sauce, 1/4 tsp

Sugar, 1/2 tsp

For the Stir Fry:

Chinese celery, 1 stalk. Chopped into ~1.5 inch sections. You can also use the leafy tops of western celery.

Scallion, 1 sprig. Chopped into ~2 inch sections.

Onion, ~1/8. Cut into chunks.

Spicy red chili, 1-2 chilis. Sliced.

Curry Powder, 1/2 tbsp.

Sauce from above.

Fish sauce, to taste. Add in a little more fish sauce if it’s not salty enough.

Process:

Prepare the squid: clean, then remove the bone. Cut into ~2 inch squares, then slice little groves ~2mm apart in a checkerboard pattern.

Peel the shrimp, then butterfly. Remove the vein. Rinse, then marinate with the ‘marinade for the shrimp’.

Mix the sauce.

In a wok over a high flame, add in ~1/4 cup of oil. Heat up until bubbles are rapidly forming around a pair of chopsticks, ~160C, then add in the shrimp. Fry until cooked, 30-60 seconds, then heat off and remove.

Dip out all but 1.5 tbsp of the oil. Swap the flame back to high. Add the squid and the just-cooked shrimp, brief ~15 second fry. Add the celery, scallion, onion, and chili, stir fry for ~30 seconds. Swap the flame to medium, and add in the curry powder and the previously prepared sauce. Let it come together and thicken, ~90 seconds.

Season with a touch more fish sauce, if needed.

What a wonderful and informative article, thank you! I was discussing the same subject with a dear friend and fabulous cook from Sri Lanka. She said that in her country they consider "curry" a cooking method and not an ingredient which makes a lot of sense as each family has their own spice mixes. Interestingly enough, the use of spices mixes was quite prevalent in Europe from the early Middle ages to the 17th century after which it was slowly forgotten in favour of herbs and other condiments. Fascinating history.

::Madhur Jaffrey jokes in An Invitation to Indian Cooking that she images the [curry powder] origin story a bit like this:::

I don't think that's a joke, really—I'm pretty sure that's how it actually happened.

The Imperial Officer played by David Niven, meanwhile, is also getting rich off of his very Anglo, and less spicy and piquant, version of the "curry powder" his cook threw together! Only difference is, Niven's is called "ENGLAND'S Best Curry Powder", and people buy Khansamah's version for a more "authentic" experience....

...kind of like how I make tacos using a jar of store-bought salsa, a couple pounds of hamburger, garlic powder, chopped onion, simmer for an hour, serve with warmed-up store-bought "hard taco shells", shredded iceberg lettuce, shredded cheddar cheese, and sour cream! It's the recipe I learned from my Mom who learned it from Grandma, and the only difference between their and mine is that she used to have to fry her own tortillas—until she taught us kids how to do it!

For the record, my Mom and Grandma were Scots/Irish, and Grandma moved to California as a little girl over a century ago. She's cooking "Mexican food" as White people of the early/mid 20th Century Southwest did, and which can be found at any Taco Bell—which was unsurprisingly founded in a town between Los Angeles and San Diego called "Downey" in the 1950s by Glen Bell (though it didn't get the "Taco Bell" name until 1962!).