What is Lao Gan Ma, and can you make it at home?

How to make the 'San Ding' Lao Gan Ma, and it's context in Guizhou cuisine.

Lao Gan Ma chili crisp. It’s a beloved condiment in China and its cult following in the West has grown to a point where… maybe it’s not quite “cult” anymore.

There’s been a lot of ink spilled on the internet about how tasty Lao Gan Ma is, so I’ll spare you the whole gratuitous “this-stuff-is-awesome-I-use-it-on-everything” spiel. It’s an awesome sauce. But yet, in spite of (and maybe a little bit because of) its burgeoning popularity, there seems to be… a lot of misinformation out there about what Chili Crisp is, where it comes from, and how it’s made. So even though I’m far from an expert on the topic, I thought it might be useful to clear the air a bit.

Where Lao Gan Ma Chili Crisp is from

Chili crisp is a condiment from the Guizhou province.

Not familiar with Guizhou food? Excuse me while I… wax poetic. Because really, Guizhou cuisine is probably one of my personal favorite regional cuisines in the country – and by extension the world at large.

I mean like, everyone loves Sichuan food. And why not? It’s an awesome cuisine, well deserving of every bit of its international repute. But it’s far from the only province in China that loves its chilis. There’s an old, increasingly worn out saying in China that the Sichuanese can handle their heat (四川人不怕辣), that the neighboring Hunan province isn’t afraid of their chilis (湖南人辣不怕), but that people from Guizhou are afraid of food that’s not spicy enough (贵州人怕不辣).

I know that I probably just made any Chinese speaker here groan at the mere reference of that, but it does, I think, help illustrate at least part of the essence of Guizhou cuisine. I strongly believe that Guizhou food itself is simultaneously some of the best in China but also some of the most unapproachable for unsuspecting or picky tourists/expats. It's intensely spicy, sour, smoky, and makes heavy use of fermented ingredients. A common aromatic is 'yuxingcao' which I love but I've seen others seem to gag on.

It's a cuisine with strong, bold, and unrepentant flavors... which could double as a solid analogy for the province itself. It’s the kind of place that has that sort of… charismatic grit to it. The province is famed for their Baijiu and people there are hard drinkers – the capital Guiyang probably has the most bars per capita of any city in China (including my favorite bar in the whole country, the – now original – location of Tripsmith). The city center's packed to the brim with street food, you'll see charcoal grills at a plurality of corners. Wintertime, you'll see people making wood fires on the street and inviting you over to sit my the fire. You think it's just because you're a foreigner, but then you see them do the same to other random passerbys. It's just part of the culture there.

Specifically? You can see stuff like this on menus and in markets in Guizhou:

Catfish hotpot in fermented tomato soup. This stuff is awesome.

Semi-digested herb with beef pot (I lovingly call this “cow shit pot”, no judgement intended, it’s funky and pretty awesome)

… and the list goes on. It’s just… fascinating as all hell. While it’s always tough to decide on your favorite [whatever], it’s undeniably one of the most underrated cuisines (though hat tip to Hubei food in that regard as well).

What Lao Gan Ma Chili Crisp Is:

You might be familiar with “Chinese Chili Oil”. You know… the stuff you top Sichuan cold noodles with, or perhaps mix with vinegar as a dipping sauce for your dumplings? Right. That kind of chili oil originates from the Sichuan province, and in Mandarin is referred to as Youlazi (油辣子).

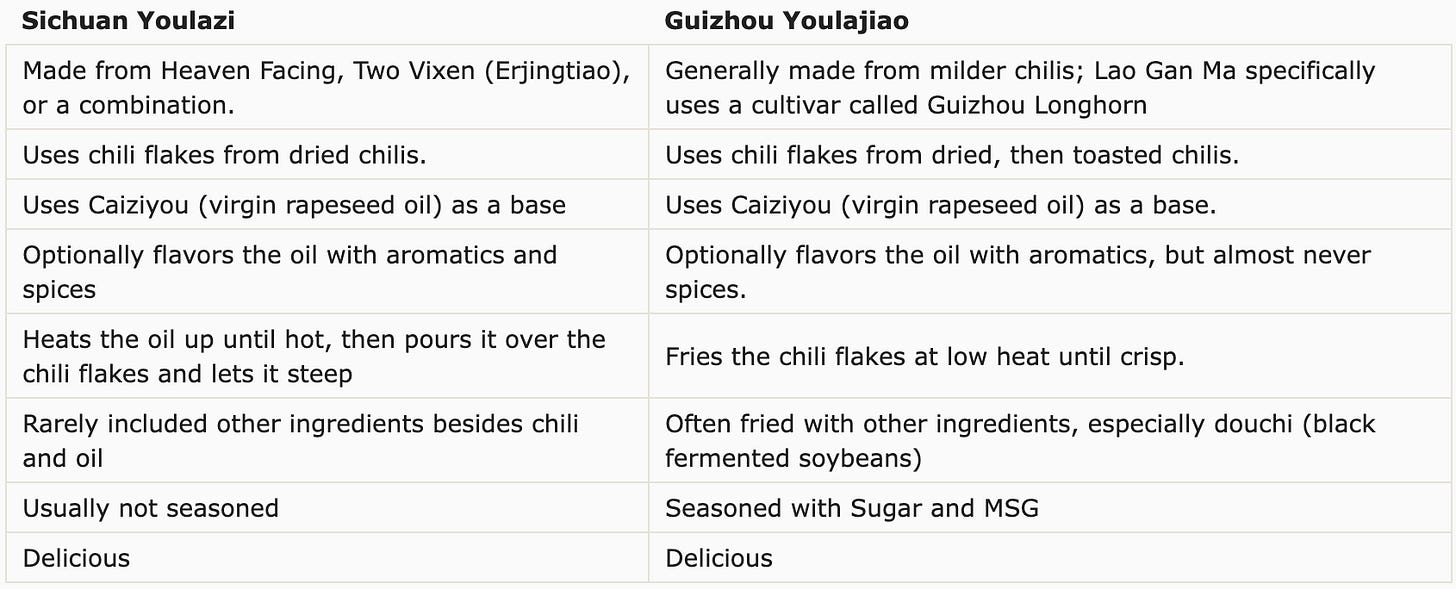

Lao Gan Ma, meanwhile, is a type of chili oil from the neighboring Guizhou province called Youlajiao (油辣椒). Potentially confusing, I know. And given how the Anglosphere’s got an increasingly solid amount of information on how to cook Sichuan food (and a relative dearth of information on Guizhou cuisine), most “chili crisp” recipes you see in English online are really a riff off the former – that is, Sichuanese Youlazi.

There’s some important differences though. Most notably, in Guizhou the chili flakes are fried until crisp, which means that the flakes themselves are an important part of the condiment. The Sichuanese sort, meanwhile, tends to use a higher ratio of oil (though depending on the cook, either one can be more/less oily). Some other similarities/differences:

It’s actually used in a very similar way as how Youlazi chili oil is used in Sichuanese cuisine – that is, as a condiment, dipping sauce, and topping. A few highlights for how it’s used:

• A topping for Juanfen, rice noodle rolls.

• An optional topping for the increasingly popular Lamb rice noodle soup.

• A dipping sauce for “rice tofu”

• A dipping sauce for blanched vegetables

A brief history of Lao Gan Ma

So it’s in this kind of context that Lao Gan Ma was born. While these sorts of origins stories are often apocryphal, Lao Gan Ma started… in 1996. Close enough where there’s probably more truth than fiction here.

If you take a look at a Lao Gan Ma bottle, there’s a woman there staring at you (and silently judging you for being about to drunkenly put the sauce on a McFlurry-with-French-fries at 2 am). That’s Tao Huabi, the founder of Lao Gan Ma. The story goes like this: back in the early 90s, Tao Huabi had a Liangfen stall (this stuff) on the side of the highway outside of the capital of Guiyang. Liangfen is a dish that’s usually topped with Youlajiao chili crisp, and Tao Huabi had a douchi-heavy version was quite popular. So popular, in fact, that she started making larger and larger batches of her chili sauce and selling it out to other vendors.

Tao Huabi’s “aha! moment” came one day when she was a bit under the weather and didn’t feel like making her signature chili topping. Without the chili sauce, she saw her regular customers going elsewhere… realizing that people really loved her chili sauce, not her Liangfen. And with that, she went strictly into the sauce making business.

But it’s actually what came after that that I’m personally a bit more interested in, and frustratingly there’s not a ton of readily information out there. It appears that they started to distribute the product outside of the Guizhou province at around the turn of the millennium, and sales exploded after that. The fundamental question that’s always kind of nagged me was how a specific kind of not-so-famous-chili sauce from the Guizhou province (historically China’s poorest province) ended up becoming one of the top condiments in the country.

I have no good answers here. I mean, at some level we could probably just go occam’s razor on this one: the stuff tastes good. But I think at least part of the answer could have to do with China’s internal migration.

This is all extremely anecdotal, so just take at face value. When I first moved to Shenzhen back in ’09, I lived on the couch of my buddy from university, who was originally from Yunnan. And it was from him that I first learned about Lao Gan Ma – I’d often see him munching on rice from a rice cooker, with a side of Pu’er tea, topping his rice with chili crisp.

See, my friend worked in sales, and would often commute into Hong Kong. And when he was in the mainland? Much of his job consisted of entertaining Hong Kong businessmen on trips throughout the PRD. Especially back in the day, that’d mean (1) eating at a nice Cantonese restaurant (2) going to KTV and (3) partaking in uh… nighttime activities. So this meant that much of the time he was eating Cantonese food. And while he liked Cantonese food (he was particularly into Cantonese soups), it’s certainly not the same taste as you’d get in Yunnan – in particular, Cantonese food’s missing the same kick of spice that you’d get in Han Yunnan cuisine. So for him, Lao Gan Ma helped bridge that gap.

At the same time, Steph (who’s Cantonese) had a colleague at her company from the Hubei province, and had much the same introduction to Lao Gan Ma – he’d bring it into work, and top the stuff that they’d eat at their Cantonese canteen with chili crisp. And if you look throughout the country, much of China’s internal migration consisted of folks from interior provinces (i.e. places with spicy cuisines like Hunan, Sichuan, Jiangxi, and Hubei) to the coast – places with comparatively more mild food, like Guangdong, Fujian, Jiangsu, and Zhejiang. It’s certainly not enough to generalize a trend, but people moving to the coast and using Lao Gan Ma as a sort of “taste of home” feels common enough to be at least part of the explanation for its burgeoning popularity.

How to Make Chili Crisp

Ingredients

So forgive that backstory – I know how passionate people can be on the subject of recipe backstories ;)

There’s a million types of Chili crisp in Guizhou – as evidenced by that wide selection of Lao Gan Ma products. The variety that we’ll be doing is the sort called “San Ding” (三丁, “three dice”) chili crisp. If you’ve ever had that Lao Gan Ma with the crispy fried tofu in it? That’s the sort that I’m talking about.

Now note that chili crisp really is more of a technique than a mix of ingredients. Don’t have some of these ingredients? Use what you got. You’ll need (1) chilis (2) oil and ideally (3) MSG to season. Dick around and make your own creations – that’s half the fun of cooking, after all.

Dried Chilis, 30g; Laoganma uses “Guizhou Longhorn” (鸡爪辣), sub with ~20g Kashmiri chilis and ~10g arbols. Ok, so unless you happen to live in China, I wouldn’t pull my hair out trying to find the exact same chili that Laoganma uses. Just for reference and all. Guizhou Longhorn looks and basically tastes like a cross between Kashmiri chili (used in Xinjiang cuisine) and Sichuan Erjingtiao (one of two go-to chilis in Sichuan). Admittedly knowing nothing about how chilis are crossed/made, it actually wouldn’t surprise me if it was exactly that. Guizhou longhorn tastes basically like a slightly spicier Kashmiri chili, so I’d recommend a mix of Kashmiris and Arbols to sub it.

Oil, 1 cup; preferably Sichuan caiziyou (菜籽油) or Indian mustard seed oil, or a good peanut oil. Ah, Caiziyou. The basis for southwest Chinese cooking and frustratingly almost completely unavailable in the West. Caiziyou is a sort of virgin rapeseed oil, has this sort of deep almost funky flavor, and it the go-to frying oil in Guizhou, Sichuan, Yunnan, and Hunan. If you can source it, Indian mustard seed oil is actually very close in taste, so that’s another possibility. If you can’t find either, well… use a tasty peanut oil. It’s generally what Sichuan restaurants outside of China do, and hey, it works. As a sidenote, I was chatting with Mala market, and they were saying that they were getting Caiziyou in sometime next month. Cross your fingers.

Fried or roast peanuts (炒花生), ~1/4 cup. First leg of the San Ding, i.e. the “three dice”. This would use fried peanuts, but feel free to alternatively use roast peanuts. If you’re curious about the Chinese method of frying peanuts, check out the Appetizer 101 post here.

Dougan, i.e. hyper-firm tofu (豆干), 60g. Second leg of the “three dice”. Dougan, for the unaware, is a sort of pressed hyper-firm tofu (sidebar: they should really just sell this stuff to Americans, who generally seem to prefer tofu as-firm-as-possible). If you can’t find it, you could alternatively take some super-firm tofu and press it yourself, or swap for a smoked tofu. You can also totally skip it.

Datoucai preserved turnip (大头菜), 40g -or- Sichuanese Zhacai (). So doutoucai is one of those Chinese dried-and-fermented preserved vegetables, originally made from radish – Laoganma has a real obvious kick of the stuff. I have seen it at Chinese supermarkets in the West, so it is possible to source… but if you can’t find it you could alternatively toss in Sichuanese Zhacai, which would hit the same note and can be purchased online. Someone asked us if they could sub this with Tianjin Preserved Vegetable and uh… maybe. It’d worry that the leaves of Tianjin Preserved vegetable might scorch, so if going that route try to use stems. Or again, you could also skip this, as not all chili crisp has preserved vegetable in it.

Douchi, fermented black soybeans (豆豉), 30g soaked in ~2 tbsp Baijiu liquor -or- bourbon. So Lao Gan Ma has their own proprietary method for making douchi – it’s even been the subject of lawsuits. Sichuanese-style Douchi would probably be the closest, but for this recipe we just used Cantonese-style Douchi, because that’s what usually available outside of China. We’ll be soaking those in liquor to help bring out their flavor – Chinese Baijiu (sorghum liquor) for authenticity bonus points, but I think that bourbon would also fit the flavors we’re working with here quite well. Whatever you do, please don’t try to sub this with that “black bean and garlic” sauce that Lee Kum Kee produces – I… really dislike that stuff, and IMO it’s no sub for that rich, chocolate-y taste that douchi brings. If you can find the fermented beans themselves, just skip them.

Aromatics: ~3 cloves garlic, ~2 inches ginger (姜). Both lightly crushed. Weirdly, like all the recipes I’ve seen online in English for chili crisp also include shallot… which is not a thing in Guizhou (shallot does make an appearance in China, but we’ve mostly seen it in Guangdong/Fujian cuisines). But I mean… if you like shallot add some shallot, why not.

Whole Sichuan peppercorns (花椒), 2 tsp. We’ll be toasting and grinding these.

Sesame seeds (炒芝麻), 2 tsp. We’ll be toasting then cracking these.

Optional: one small block of furu, fermented tofu, mashed (腐乳). Probably only a minority of Guizhou Youlajiao added this, but during research Steph found one Guizhou chef that added it and did it on a whim. Definitely works, adds a subtle fermented undertone. If you happen to have a bottle on hand, toss one in; if not, don’t buy a bottle just for this.

Seasoning: ½ tsp sugar, ½ tbsp MSG (味精), salt to taste if you’re dramatically altering this recipe. I personally love Lao Gan Ma and am a big booster for MSG as an ingredient. But in the words of one random heavily-downvoted Redditor on here that I weirdly remember vividly… “Lao Gan Ma has enough MSG to choke a horse”. It’s super heavy on MSG – we used a half a tablespoon here, which’s already a lot... to be honest, Lao Gan Ma might have even more. Start here, season to taste. And in a similar sense, we didn’t add salt here (given all the salty ingredients, plus we’ll be toasting the chilis in salt)… but definitely taste & adjust at the end here.

Process

Ok, high level overview here: prep your ingredients (most notably soaking the douchi), toast the chilis, pound into a flake, flavor the oil with aromatics, fry some of the other ingredients, add in the chilis, fry on low heat for ~5 minutes until crisp, add in the seasoning/Sichuan peppercorns/sesame.

If you want to just into the video straight in at this point, it’s about four minutes in here.

If using, soak the douchi in the liquor for at least two hours.

Snip the chilis into ~1cm sections (don’t deseed), then toast in a dry wok for ~7-8 minutes until they’re “chestnut colored”. So there’s a cool technique here if you’re so inclined: if you’ve ever toasted chilis before, you know that they have an annoying tendency to scorch in some parts, while being barely toasted in others. One technique that’s used in Guizhou is to add salt to the wok along with the chilis – this’ll help the chilis toast evenly. So if you like, add a small bag’s worth (~250g) of salt into the wok together with your chilis, and first toast over a medium flame for ~2-3 minutes. Once you hear small “popping” sounds from the salt, reduce the flame to as low as your stove can go, and continue to stir and toast for ~5 minutes. You’re looking for something roughly this color in the end, though to be honest we could’ve gone even farther there… but it’s generally safer to under-toast than over-toast. Strain the salt out using a colander, giving the chilis a number of good whacks to get off any excess salt. That salt though? Still good to use… it doesn’t really take any flavor from the chili. Strain out any seeds that made their way into the salt, and use the salt like you would any other salt.

Add the chilis to a mortar and pound into flakes. You could alternatively use a food processor here I’d imagine. Just don’t go too fine – pounding it by hand you’ll get some chilis that’re more of a powder, some that’re more of a flake… that’s fine, that’s what we want. I know this isn’t super clear, but something like this is fine.

Toast the Sichuan peppercorns. Over a medium flame, toss your Sichuan peppercorns in a pan/wok and toast for ~2 minutes, or until you see small oil splotches start to form on your pan.

Toast the sesame seeds. Over a medium flame, same deal with the sesame seeds. For the small amount here, it’ll probably also only need like ~2 minutes – you’ll know the seeds are done once you can hear a light “popping” sound and they begin to darken ever so slightly. It’s helpful to make a big batch of these and have them around though, if you’re using more then it might take more like 3-5 minutes until finished.

Grind the peppercorn into a powder, slightly crack the sesame seeds. Toss the Sichuan peppercorn into a mortar and grind into a powder (or use a spice grinder). For the sesame seeds, we only want to give them a super super brief pound just to slightly crack them open – if you don’t own a mortar you could do that with the handle of a knife or just forget it I guess.

Prep the rest of the ingredients. Cut that Dougan (i.e. the hyper firm tofu) into ~1 cm dice, peel then get the datoucai preserved turnip into the same ~1cm dice (zhacai’ll usually come pre-diced), ever so slightly smash the ginger and the garlic.

If using, fry the dougan until crisp. Sort of a shallow fry here, we used a saucepan with ~2 cups of oil. Toss the dougan in when it’s still all cool, then swap the flame to medium. Stir periodically… this isn’t too heavy of a fry here, we were looking at ~125C once everything got up to temperature. After about ~10 minutes, once they’re golden brown… take them out. Note that this’ll be a different oil than what we’re using in the next step: you can fry with really whatever the hell you want here.

To make the chili oil: first heat your ~1 cup of oil until smoke point, ~220C, then shut off the heat. This will “cook” the oil, and it an important step if using Sichuan Caiziyou or Indian Mustard Seed oil. It’s optional but recommended if using peanut oil.

Wait until the oil’s cooled down a touch, ~170-180C, then swap the flame to low and begin to make the chili oil.

Garlic and ginger, in. Fry for ~2 minutes until the garlic is ever so slightly browned.

Datoucai Preserve Turnip/Zhacai, in. Fry for ~5 minutes or until the preserved vegetable begins to shrink a bit.

Remove the garlic and the ginger.

If using, add the mashed fermented tofu. Quick mix.

Add the douchi black fermented soybeans together with the liquor, bit by bit so it doesn’t pop too hard on you.

Fry for ~5 minutes or until most of the moisture’s bubbled away.

Add the chili flakes.

Stir constantly and continue to fry on low heat. For reference, this was ~90-100C.

Add the peanuts and fried tofu. Quick mix.

Season with sugar and MSG. Taste, add salt, if it need it.

Sichuan peppercorn and sesame seeds, in. Heat off.

Let it cool down a touch, then jar it up.

This’s best at least one day later.