The En-Rice-ification of Yunnan

What shifting from the Tai sticky rice system did to Yunnan food - featuring two stewed greens recipes from either side of the Mekong (Northern Thai Cho Phak Kat and Yunnanese Suan Pa Cai)

China’s southern borders used to be more… abstract than they are today.

You see, stretching all the way back to the Tang dynasty, difficult-to-administer mountainous and border regions used to be organized a bit differently than the rest of the empire. The system was first referred to as the Jimi (羁縻) system and later the Tusi (土司) or “chiefdom” system, and it’s a kind of political organization almost as old as… political organization is. After conquest, instead of being wholly absorbed into the Chinese state, local hereditary chieftains maintained most of their local autonomy – responsible for paying taxes, raising levees when needed, following along with the Chinese state’s foreign policy… and that’s pretty much it.

Much of these Tusi were centered around the Chinese southwest, in particular the non-Han areas of Yunnan and Guizhou. And of course, within these Tusi there’d be all the drama that you’d expect from heredity political structures – there’d be succession struggles, families would splinter, families would fight wars with each other, etc etc. And obviously, there wasn’t exactly passport control and border checkpoints set up in between Tusi, or the culturally adjacent Shan states in what’s now modern day Myanmar, Laos, and Thailand.

Starting in the Ming dynasty, these Tusi would gradually become formalized into the Chinese state and subjecting to more control – emphasis on the ‘gradually’, because this was a process that would ultimately take centuries. Like, it wasn’t until 1953 when the very last Tusi – the Tai princely state of Sipsongpanna, on Yunnan’s southern border – finally stepped down, marking the final end of the Tusi system.

A region split

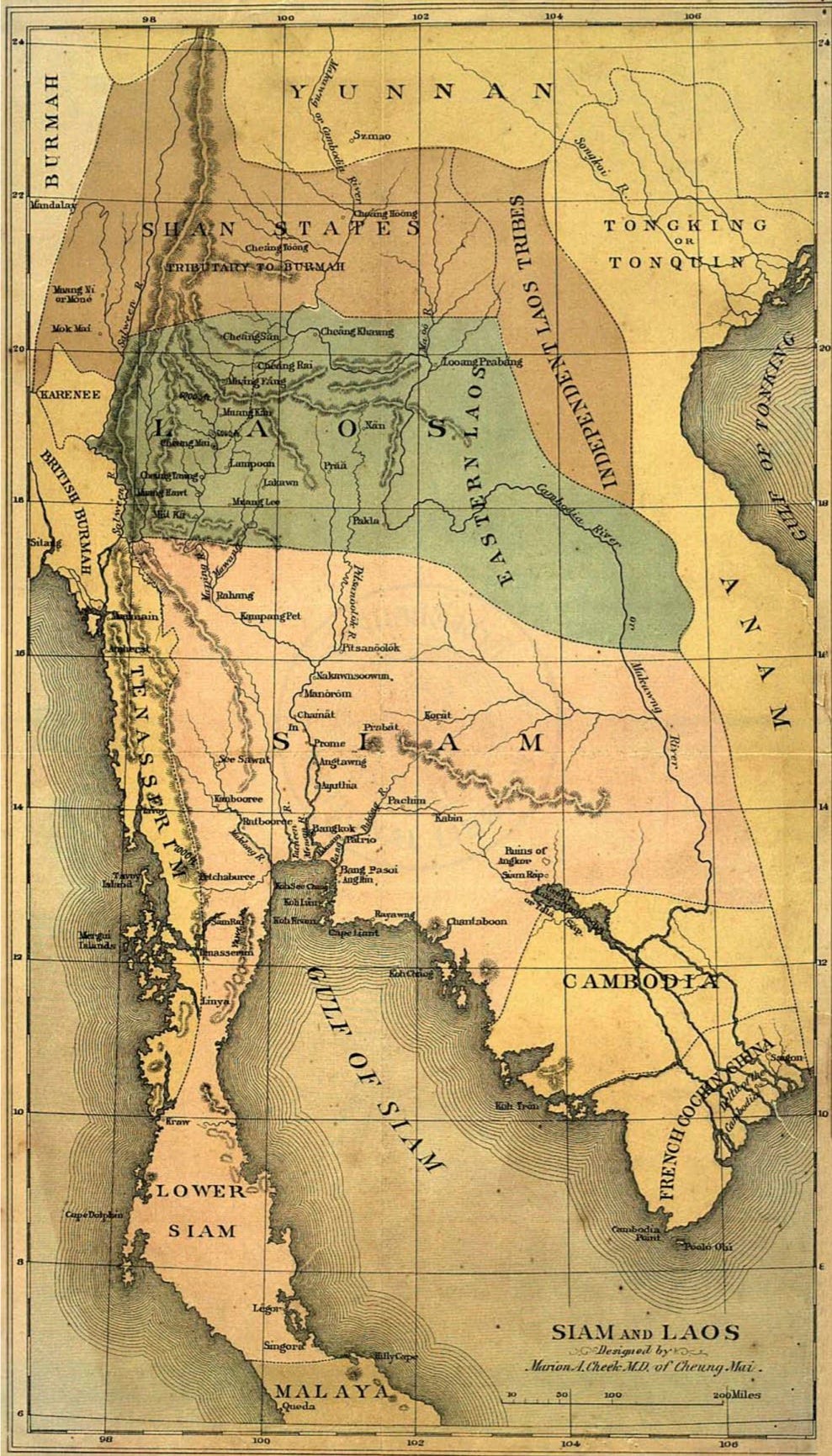

I want you to take a look at the following 1884 map, keeping the whole fluid Tusi system on the northern border in mind. Also note that “Shan states” in brown had a similarly complicated relationship with the Burmese crown, and “Laos” in blue were solidly semi-autonomous tributaries to Siam.

Practically everything from the edge of what’s marked ‘Siam’ to almost all the way up to Kunming could be conceptualized as a sort of… amorphous cultural zone. Now, compare to the modern day boundaries:

Of course, even today some of these border regions can be pretty fluid – neither Myanmar nor Laos are exactly the strongest states in the region. But for both China and Thailand, each respective state sought to integrate these formerly-amorphous regions into their nations as a whole, and were largely successful in doing so throughout the 20th century.

Now, that swath (really, the entire southeast Asian highlands) is, of course, is one of the most ethnically diverse areas on the planet – I’ve even seen some scholars compare the diversity there to Papua New Guinea. But from a high level perspective, a palpable majority of these people – the Lao, the Tai Lue, the Tai Yai, the Tai Dam, the Tai Kao, etc etc – spoke (1) some sort of Tai language (a language family of which Thai is now the prestige language) and (2) grew sticky rice.

Now, I’m sure there’s plenty of examples – throughout the world – of border regions being incorporated in similar ways as these highlands were. But to me, what makes this particular case so interesting, food wise, is that on the northern side of the border, the incorporation also coincided with a shift in the staple grain:

The Yunnan province switched from sticky rice to rice.

The Sticky Rice Eating System

I’d imagine you’re probably familiar enough with how meals can be based around white rice – it is, after all, a global staple everywhere from China to America to Peru. What’s a lot less common to see, worldwide, are cuisines based around… sticky rice. Traditionally, it’s been the primary starch throughout the Southeast Asian Highlands - like, the Lao people sometimes even refer to themselves as luk khao niaow – i.e. “children of the sticky rice”. Even today, while Thailand is famed the world over for its Jasmine rice, much of that crop is grown for export. Thai farmers (especially in the sticky rice loving North and Northeast) often grow rice and sticky rice side by side – the former for cash, the latter to eat.

Now, the way you eat a meal around sticky rice is a ton of fun. For me, it’s right up there with “family-style-with-chopsticks” and “stuff-stuff-inside-of-tortillas” as one of the world’s great eating systems. Basically, you pinch off some sticky rice, form it into a little ball or saucer in your hand, and then use it to grab and consume the main dish. Here you can see what that whole process looks like in practice, via one of our favorite Thai-Isaan cooking vloggers:

Now let’s swing back to China and zoom into Sipsongpanna - that very last Tusi princely kingdom to be absorbed in the 1950s. Before that time, the vast majority of the population in the region were Tai peoples – in excess of 90%. And perhaps predictably, this meant that over 90% of the farmland was also allocated to… sticky rice.

It’s not just because of economics that sticky rice is beloved in Tai areas - it’s cultural too. In Sipsongpanna specifically, it was considered easy to carry (especially wrapped in banana leaf), and still had a nice texture when eaten cold in the fields. And to make a tasty-enough simple meal, you’d only need a bit of fermented soybean or pickled vegetable to go along with it.

In the 1950s however, the government began to push sticky rice growing regions in the Southwest to grow white rice instead. It’d be a more… fungible… commodity within the larger Chinese food system, but more importantly, yields for white rice are higher. Theoretically, at least. While sticky rice does seem to grow better in highland areas, you can get two harvests in per year for white rice, instead of the singular harvest for sticky rice.

The wisdom of that policy is likely debatable, and I don’t know enough about agriculture to tally the score. But it was in the 1980s when the shift from sticky rice to white rice began accelerating in earnest, as farmland began to be allocated increasingly towards the cash crops of (1) banana and (2) rubber. At the same time, together with Deng’s reform and opening, the Hukou (China’s internal passport) system began to loosen up as well. Drawn by the opportunities presented by said cash crops (as well as a nascent tourism industry), people from other provinces – notably, Hunan – began to migrate to the area, and bring their eating customs with them.

So these days? In Sipsongpanna, only the oldest generations in the villages tend to stick to the sticky rice diet. The younger generation has swapped almost completely to either rice or rice noodles, and sticky rice has been reduced to a special occasion food – or perhaps something that you can see in rituals.

But… “so what?” you might ask. “So their rice got a little less sticky, what’s interesting here?”

In food circles today, against the modern backdrop of agricultural surpluses, cheap meat, commercialized eateries, and celebrity chefs… we can sometimes underrate how fundamental staple grains are to the foundation of a cuisine. I think it’s why fusion restaurants can feel so listless at times – when we smash together Japanese and French, is it supposed to go with rice, or bread?

Like, imagine if one day the entire nation of Mexico woke up and decided to center their meals around Fufu instead of Tortillas. It wouldn’t just be a simple matter of less corn and more yams. I’d imagine it’d ripple through practically everything. It’d alter how people structure their meals, it’d alter how people commercialize and sell the food, and, I think, it’d undoubtedly alter certain dishes themselves.

…which bring us to our recipes today.

Northern Thai Cho Phak Kat vs Yunnanese Suan Pa Cai

This is a dish called Cho Phak Kat (จอผักกาด) that you can find in Northern Thailand.

Cho Phak Kat might not be the first thing that you might think of when you think “Northern Thai food” – the average traveler to Chiang Mai’s usually drawn to the Laabs, the Khao Soi noodle soups, the Sai Ua sausages… and not a random-looking stewed green occupying just one tray among many at the curry counter.

But in home kitchens, that green is an everyday dish – something with the same sort of cultural resonance as Mac N Cheese in the USA. I mean, there’re even folk songs on the topic:

As you might expect, it’s an eat-me-with-sticky-rice sort of dish. It’s made by boiling some pork bones or ribs to make a sort of soup base, then stewing some greens in said base. It finishes with tamarind juice to give things an obvious sour kick, and then tops things off with fried garlic and chili pepper.

To enjoy it, you’ll eat the vegetable with the sticky rice – sometimes adding a bit of kick with a bit of the fried chili pepper. You’ll also drink up the soup, of course, and maybe eat it alongside something like a bit of deep fried pork that you buy from the market.

This, meanwhile, is a dish called Suan Pa Cai (酸扒菜) in Yunnan.

At first glance, the similarities are a little too hard to ignore:

You make a pork bone base

You stew greens in it

You add an intense sour component

You top with garlic, cilantro, and chilis

But what makes this so interesting is just… how differently this fundamental idea developed on different sides of that rice-sticky rice line. Because in Yunnan, this is just a… dish.

These days, being a rice centric eating culture, Yunnan meals usually look a good bit closer to what you might see elsewhere in China. People eat family style around a number of small-to-medium sized dishes, about one per diner. You’ll then use those dishes to go along with some rice, with at least one vegetable dish generally being among them.

So Suan Pa Cai exists in Yunnan as one vegetable dish among a larger assortment of dishes – just like how Shousibaocai is a vegetable dish in Sichuan just like Furu Ong Choy is a vegetable dish in Guangdong. You can see it on restaurant menus right next to other regional Yunnan specialties like Grandma’s Mashed Potatoes or Grilled Goat cheese, as it’s often paired among richer and meatier dishes. The way I was taught to enjoy it was to go along with some late night Yunnan barbecue, to be downed next to grilled pork belly and a bit of beer.

Of course, to be clear, whether on the Chinese side or the Thai side of things… when it comes to this specific dish? We… don’t really know anything tangible about the history – a humble stewed green usually isn’t even smiled on by the YouTube algorithm, let alone the royal chroniclers of yore. Hell, the whole thing potentially could’ve spread to both Yunnan and Northern Thailand via Myanmar (more on that later in the post). What is for certain though is this:

(1) Suan Pa Cai is great with rice.

(2) Cho Phak Kat is incredible with sticky rice.

And that’s probably not an accident.

A word of warning on the upcoming recipes

So, we thought it’d be most interesting to see these two stewed greens pretty much unaltered from their Northern Thai/Yunnan forms, so… that’s what’s below, and that’s what we did in the video. To that end, both are pretty much no-holds-barred on the sourcing front, featuring a couple ingredients that might get a little challenging to recreate wherever you might be reading this from.

But if the Thai version and the Chinese version work off of the same fundamental idea to whip something up that makes sense for their respective trade networks, why can’t we try to do the same thing using stuff that’d be available at a standard western supermarket? So while we’re obviously no chefs, we did our hand at formulating a western supermarket version, which’s listed after the Yunnan version below.

Northern Thai Cho Phak Kat (จอผักกาด)

Ingredients:

Pak Kat Chon (ผักกาดจ้อน/ผักกาดกวางตุ้ง), 750g -or- your stewing green of choice, ~500-600g. More information on this specific vegetable can be found here. It has a hard stem that needs to be picked, so you’ll lose some of that 750g in the process.

Tamarind pulp (มะขามเปียก), 20g; mixed with ~1/4 cup of hot, boiled water.

Pork bones -or- ribs, ~350g

Water, 1.75L

Ingredients for the seasoning paste:

Garlic, 20g

Shallots, 4 small (1-2 large)

Shrimp paste (กะปิ), 1 tbsp

Salt, 1/2 tsp

Thua Nao (ถั่วเน่า), Fermented Soybean Sheets, 2 sheets. No direct sub here, but ~2 tbsp of roasted soybean flour could hit similar notes.

Garlic, 20g. Roughly pounded.

Dried chilis (พริกแห้ง), 6-7

Final seasoning, to taste, or:

MSG (ผงชูรส), 1 tsp

Sugar, 1/2 tsp

Optional: Rot Dee (รสดี) -or- Chicken Bouillon Powder, 1/2 tsp

Chopped Cilantro. For garnish.

Optional: Chili/garlic frying oil, ~1 tbsp

Process:

Pick and wash your stewing green of choice. Tear the green into roughly ~4 inch long sections. Meanwhile, mix the tamarind paste with hot, boiled water and cover.

To begin the soup, add the pork bones and water to the pot and bring up to a boil. Skim, then turn the flame down to a heavy simmer. Simmer for at least 15 minutes, but longer is ok as well.

To make the seasoning paste, as the pork is going, pound together all of the ‘ingredients for the seasoning paste’. (I like to add in all of the garlic at this stage, removing half and reserving once roughly pounded)

Add the seasoning paste and the greens to the pot. Cover, and boil over a medium flame until soft. Pak Kat Chon takes roughly 30 minutes. As the greens are stewing, prepare the Thua Nao and Fried Garlic/Chili Topping.

To prepare the Thua Nao, toast by microwaving for 90 seconds in medium power. Then, crack into a few pieces and pound into a fine powder.

To make the fried chili/fried garlic topping: In a wok over a low flame, fry the dried chilis in ~1/4 cup of oil until they’re crisp, ~4 minutes. Remove and reserve. In the same oil, fry the roughly pounded garlic over a medium flame until they’re just barely starting to get golden. Then shut off the heat, continue to stir fry for one more minute, and reserve.

Once the greens are soft, add in the pounded Thua Nao, strain in the tamarind water, and the final seasoning. Transfer to a large bowl. Sprinkle over the friend garlic and cilantro. Optionally drizzle over the chili/garlic frying oil. The fried chilis can top the dish or be munched on on the side.

Serve with sticky rice.

Yunnan Suan Pa Cai (酸扒菜)

While the Thai version almost universally leans on tamarind as the sour component, in Yunnan you can find a diversity. The most common route would likely be via dried or fresh Suanmugua (酸木瓜), a.k.a. “Chinese Quince”, although you can also find people using Nansuanzao (南酸枣), a.k.a. “Nepali Hog Plum” or even Fermented Bamboo Shoots.

Given that it’s eaten within the context of a larger meal, you can also sometimes see a dipping sauce to go along with it, ala Suguadou in Guizhou. For those new to the sport, I might suggest including a dipping sauce.

There are also a diversity of ingredients that can be included. Sometimes you can also see Potatoes or Beans - especially in the Southwest of the province around Dehong, who enjoy a version that’s actually kind of a dead ringer for Myanmar Thizon Chinyay (more on that later in the post).

Ingredients:

Xiaokucai (小苦菜) -or- Chuncai (春菜) -or- Rapini -or- your stewing green of choice, 500g. Picked and ripped into 2-inch long sections.

Pork bone or pork ribs (猪骨/排骨), ~350g

Salt, 1/4 tsp

Cherry Tomato (小番茄), 4-5. Halved.

Dried Chinese quince (酸木瓜), 7-8 pcs, 10g. This may be available on Amazon under the Korean name Muguaguoshi. Unfortunately, we are not sure whether this is truly the same thing or not.

Ginger (姜), 1 inch. Smashed.

Final Seasoning:

Salt, 1/4 tsp

MSG (味精), 1/4 tsp

Chicken bouillon powder (鸡精), 1/2 tsp

For the topping:

Garlic (大蒜), 1 big clove. Minced.

Xiaomila or any red spicy chili (小米辣), 2 or 3-4g. Minced.

Cilantro (芫荽), 1 sprig. Chopped.

For a Dipping sauce, optional:

Roasted -or- smoked chili powder, e.g. chipotle (煳辣椒), 1 tsp

Garlic (大蒜), 1 small clove. Minced.

Xiaomila or any red spicy chili (小米辣), 1. Minced.

Chopped Cilantro (芫荽), ~1.5 tbsp. Or, from roughly 1 sprig.

Chopped Culantro (大芫荽/老缅芫荽), ~1.5 tbsp. Or, from roughly 2-3 leaves

Soy sauce (酱油/生抽),

Salt, 1/8 tsp

MSG, 1/8 tsp

Soup, 1/4 cup

Process:

Pick and wash your stewing green of choice. Tear the green into roughly ~2 inch long sections.

To begin the soup, add the pork bones and water to the pot and bring up to a boil. Skim, then turn the flame down to a heavy simmer. Simmer for at least 15 minutes, but longer is ok as well.

Add in the greens, the salt, the dried Chinese Quince, and the ginger. Cover, and boil until soft. For Chuncai, this takes about 45 minutes.

Add in the ingredients for the final seasoning, to taste. Transfer over to a large bowl. Top with the minced garlic, the minced chili peppers, and the chopped cilantro.

To make the optional dipping sauce, mix together all the components listed above.

Enjoy next to meaty and/or rich and fatty dishes, alongside rice.

Western Supermarket Suan Pa Cai

Because sticky rice is a bit annoying to make (and many western kitchens just plain aren’t set up for it), we decided to hue closer to the Yunnan version, conceptually: a large side to be eaten within the context of a larger meal, particularly with richer sides.

For the sour component, the route we decided to go re souring was with citrus, which seems pretty universally available.

Unfortunately, we don’t have access to Quince (except in jam form), else that would likely have been the route we’d have gone in testing. If you’re feeling adventurous, that’d definitely be an interesting angle.

Instead, we went with lemon (lime was also good). But because both are a good bit sharper than either Tamarind or Chinese Quince, we decided to also supplement that with a bit of sauerkraut for some fermented depth.

For the green, we used kale because that’s the western stewing green that’s available in Bangkok. If I was in the USA, I’d likely avoid the popular-with-health-influencers-tax reach for Collard Greens or Rapini.

Ingredients:

Kale (羽衣甘蓝) -or- Rapini -or- your stewing green of choice, 500g. Picked and ripped into 2-inch long sections.

Pork bone or pork ribs (猪骨/排骨), ~350g

Salt, 1/4 tsp

Cherry Tomato (小番茄), 4-5. Halved.

Sauerkraut (酸木瓜), 1/4 cup.

Cilantro (芫荽), 1 sprig.

Ginger (姜), 1 inch. Smashed.

Final Seasoning:

Salt, 1/4 tsp

MSG (味精), 1/2 tsp

Lemon juice, juice from half a lemon.

For the topping:

Garlic (大蒜), 1 big clove. Minced.

Xiaomila or any red spicy chili (小米辣), 2 or 3-4g. Minced.

Cilantro (芫荽), 1 sprig. Chopped.

For the Dipping sauce (optional):

Roasted -or- smoked chili powder, e.g. chipotle (煳辣椒), 1 tsp

Garlic (大蒜), 1 small clove. Minced.

Xiaomila -or- any red spicy chili -or- Thai Bird’s Eye, 1. Minced.

Chopped Cilantro (芫荽), 3 tbsp. Or, from roughly two sprigs.

Soy sauce (生抽), 1 tsp

Salt, 1/8 tsp

MSG, 1/8 tsp

Soup, 1/4 cup

Process:

Pick and wash your stewing green of choice. Tear the green into roughly ~2 inch long sections.

To begin the soup, add the pork bones and water to the pot and bring up to a boil. Skim, then turn the flame down to a heavy simmer. Simmer for at least 15 minutes, but longer is ok as well.

Add in the greens, the salt, the tomato, the sauerkraut, and the ginger. Cover, and boil until soft. For Kale, this takes about 60 minutes.

Add in the ingredients for the final seasoning, to taste. Transfer over to a large bowl. Top with the minced garlic, the minced chili peppers, and the chopped cilantro.

To make the optional dipping sauce, mix together all the components listed above.

Enjoy next to meaty and/or rich and fatty dishes - e.g. fried chicken, buttery biscuits, barbecue, etc etc.

Is this all just Burmese actually?

Something that’s incredibly frustrating when researching Yunnan-North Thailand connections is the nagging feeling that the cuisine of Myanmar is somehow a ‘missing link’ between the two. As way of example, that ever-so-famous Chiang Mai noodle soup – Khao Soi – is widely considered in the North of Thailand to be a Yunnanese Chinese Muslim dish. Khao Soi obviously doesn’t exist in Yunnan (inland mountainous Chinese provinces generally aren’t know for their coconut milk soups), but an extremely similar soup does exist in Myanmar by practically the same name. And the specific type of noodles that’re used in Khao Soi are also used in a few other Yunnanese dishes like Mala Mixed Noodles – and are sold dried under the name “Myanmar Yellow Noodles” (缅甸黄面).

It’s something that feels so… tantalizingly close to being explained, but wikisurfing and eating around tangential cuisines can only get you so far. At some point, you need to go there, get your feet on the ground, eat some food and talk to people. And unfortunately, that’s not exactly… possible as I sit here and write in the twilight of 2023.

It’s a similar case for this dish. As you might expect, Myanmar seems to have their own version as well. It seems to belong to a category of sour soups called Chinyay Hin (ချဉ်ရည်ဟင်း) that you can find from Upper Myanmar to Lower Myanmar, and if you copy/paste that Burmese script into Google images, you can find certain soups that’re absolute dead-ringers. Going down the rabbit hole, there’s also this soup called Mone Nyhainn Hcaw (မုန်ညှင်းစော) which… I think we can be pretty confident is the same thing:

Tantalizingly, many of these soups seem to split the difference between the Thai versions and the Yunnan versions. The above video sours with Tamarind, but include tomato and tops with garlic and chili pepper in the Yunnan style. There’s also seems to be a dish called Thizon Chinyay (သီးစုံချဉ်ရည်) that looks… basically the same thing as the Tai Yai (i.e. Shan people’s) style of the dish in Dehong, the area of Yunnan near the Myanmar border.

Obviously, we need to learn more about Myanmar cooking before we can say anything on the topic. Never been, don’t know the language, much of the above is just from breathless wikisurfing and going down YouTube rabbit holes. But because we just can’t help but shake the feeling that there’s a there there, we decided to bug our friend Pywee to whip up the version that her family makes in her hometown in the Kayin State.

Pywee’s Mone Nyhainn Hcaw

We’d previously bugged Pywee to make both Mohinga and the aforementioned Ohn No Khao Swe with us (both intense dishes, particularly Mohinga), so when I broached the subject with her on these stewed greens, she seemed almost… confused.

To her, it’s such an everyday dish that it’s almost not even… a dish. Seemed practically akin to asking a Cantonese person to stir fry some Choy Sum with garlic.

Her version is meant to be eaten together with rice – like, eaten with the same bite. It’s also the most savory and least sour of the three versions – she said that often her family didn’t even add any sour component at all (which does cast a little doubt on whether it’s exactly the same thing, but hey).

The end result was very delicious. I might even like it the most out of all the versions - it’s definitely the most over-rice-able, in my opinion.

Ingredients

Pak Kat Chon (ผักกาดจ้อน/ผักกาดกวางตุ้ง) -or- your stewing green of choice, 400g. This was just the green that we have around in Bangkok, use what’s local.

Tamarind pulp, ~1.5 inch; mixed with ~1/4 cup of hot, boiled water. Basically just a knob.

Pork bones -or- ribs, ~350g

Water, 1.75L

Cilantro, 2 sprigs. Root and leaves separated. Roots added in with the pork, and cilantro added to serve.

Ginger, ~1 inch. Smashed.

Initial seasoning to be mixed in with the pork soup:

Rosdee bouillon cube, ~1/2 cube. Substitute with 1 tsp chicken bouillon powder and a sprinkle of white pepper and garlic powder.

Salt, 1/4 tsp

Garlic, 2 cloves. Roughly minced.

Thai Birds Eye chilis, ~20. Smashed and roughly minced.

Shallot, 1 large. Sliced.

Cherry tomatoes, 3. Halved.

To fry the vegetable:

Oil, 1.5 tbsp

Fish sauce, 1/2 tbsp

MSG, 1/2 tsp

Final seasoning:

Fish sauce, 1 tbsp

MSG, 1/2 tsp

Process:

Just like the other recipes, pick and wash your greens. Mix the tamarind pulp with the hot, boiled water.

Then, Pywee begins by blanching the pork bones. To do so, add the pork together with enough cool water to just barely submerge. Bring to a boil, and boil for ~3 minutes. Toss the water that’s inside and give the bones a quick rinse.

Add in the 1.75L of cool water and bring to a boil. Add in the cilantro root, the ginger, the ‘initial seasoning to be mixed in with the pork soup’. Keep at a light boil/heavy simmer and cook until it’s beginning to soften, 15-30 minutes.

Meanwhile, in a wok over a medium-high flame, fry the chopped garlic until fragrant, ~30 seconds. Add in the greens and stir fry for 1-2 minutes. Add in the fish sauce and MSG and mix. Transfer over to the pot of soup.

Add in the chilis, the sliced shallot, and the cherry tomatoes. Stew, covered, until soft, ~30 minutes.

Strain in the tamarind juice, and then add in the final seasoning to taste.

Serve with rice.

Sources and Further Reading/Watching:

The information on the Jimi/Tusi system was a bit of a hodgepodge of a reflection from both mine and Steph’s reading, but you can read more about it in the excellent Empire at the Margins: Culture, Ethnicity, and Frontier in Early Modern China. The discussion on Southwest China begins in Chapter four.

For more information on the ethnic makeup of these border regions, a logical starting point might be James C Scott’s Art of Not Being Governed, which’s probably the most popular book on the region. I’d caution, however, that said book’s thesis is pretty controversial, so I’d recommend supplementing it with the Journal of Global History’s issue Zomia and Beyond. A nice overview of Tai migration in the region would be Chris Baker’s From Yue to Tai.

Much of the discussion on the transition from sticky rice to rice in Sipsongpanna was via Yang Zhuhui from the Minzu University of China in Beijing, summarized in this excellent article. It’s in Chinese, but Google Translate does a reasonable enough job with it.

The Thai version of Cho Phak Kat was largely based around the version presented in the North Thai Information Center from Chiang Mai University. Fantastic, fantastic bilingual resource.

This was supplemented with this excellent video from the YouTube channel Kratip (wish they had more videos), as well as this recipe from one of our favorite Thai vloggers, this recipe from the always-great Boontiwa Indoor, these two recipes from Pantip (the Thai equivalent to Reddit), and chit chatting with the owners at our local Northern Thai curry counter here in Bangkok. For more information on the cultural context, we worked through this “Flavor of Hometown” podcast from Thai PBS together with our Thai tutor.

In this sentence, are you saying that you would or wouldn't use collard greens?

"If I was in the USA, I’d likely avoid the popular-with-health-influencers-tax reach for Collard Greens or Rapini."

I was clicking through your recipes today and I have some collard greens (and almost everything else for the western version) in my fridge right now...

Sumak might make an interesting sub for the sour notes. Pretty available in middle eastern food stores.