Cantonese Congee 101

How to make a Shunde-style Shenggunzhou, one of the world's great - and surprisingly easy? - congees.

Seeing dishes in the midst of being adapted is equal parts interesting and bizarre.

Online, it’s something that I’ve notice quite a bit with congee. Because from a cursory google, you can find two broad categories congee recipes. You can, of course, find the true-blue-straight-from-Asia varieties, courtesy of the likes of Lucas Sin and Made with Lau (and a little farther down the page, us). After all, congee is one of the world’s comfort foods – an every day breakfast, nourishment for the sick – a staple dish for cuisines as disparate as Filipino and Korean; Cantonese and Burmese. It makes sense that it’s not exactly difficult to find an authentic recipe.

But I think that learning about that global ubiquity also piqued the curiosity of those that didn’t grow up with congee. So as befitting the internet in 2024, you can also find a metric ton of… western creators and media outlets that hop on and deliver up congee recipes themselves.

And I guess I can’t help but be a touch fascinated by that second category. Whether on YouTube or Reddit, there’s practices that would be… let’s say, unorthodox to a congee in Guangdong. People will toss in stir fries and chili oils, hit it with a big glug of soy sauce, or – perhaps most commonly – cook the rice in roasted chicken stock.

Because it’s such a… western way to think about rice. Like, take the example of Paella, or Risotto, or hell, even something like Mexican Red Rice. The rice itself gets seasoned, flavored, and is served as a side or even a centerpiece in and of itself. Perhaps it’s an instinct that we picked up from the Middle East with their Kabsas and Pilafs.

In much of East and Southeast Asia, however, rice is a staple grain. It’s the base that flavors are added to, or next to. It’s the dinner roll, the sandwich bread. And just like how you wouldn’t mix Lao Gan Ma into a bread dough, you also wouldn’t make your white rice – or congee – with chili oils and the like incorporated inside. You’d eat your flavorful stuff on the side, or maybe, maybe on top.

So what happens when the humble congee enters the more flamboyant Western rice cooking tradition? Well… I think something a little like this:

Now, because this is indeed the internet, I want to be clear here: I’m definitely not trying to dunk on Ethan Chlebowski. After all, he’s not claiming his congee is an authentic rendition or what not. More than anything, it’s just really interesting to see the direction his mind went with this. He started by frying a grated mirepoix, then deglazed with stock and cooked his rice in the mixture. On the side, he fried up an (I think vaguely Dan Dan inspired?) ground pork/chili topping seasoned with soy sauce and Hoisin, and then liberally topped the congee with the ground meat mixture, together with a big spoonful of chili oil.

This is… pretty far away from how congee is enjoyed in Asia. He definitely couldn’t serve the thing to Steph, sure, but… adapting the thing to his American tastes? Why the hell not? After all, it’s that same instinct that led to the wild world of Asian bakeries, Japanese Yoshoku fare, and Cantonese Chachaanteng. If the English language internet wasn’t a bubbling cauldron of culinary cultures smashing together at the speed of optical fiber, well, that’d be a pretty enormous waste of potential.

And yet, if I did have one criticism of some of these concoctions, is that they can sometimes seem a touch… texturally lackadaisical. I rarely, if ever, see people be purposeful about the specific rice texture that they’re going for. Are you aiming for something thin, soupy, with intact grains? Or are you shooting for something thick and pasty? Or something in between? Each end result will require a different technique.

For example, many online recipes start their congee with leftover rice. This is absolutely a legit technique, and in China produces a thin congee variety called paofan (泡饭). But this’s a congee that should be quite thin - Steph even objects to my translating it as a ‘congee’ (she would go with ‘rice soup’). Because if you blindly tried to boil cooked rice down in an attempt to mimic something like a Cantonese dim sum congee, the grains will (1) still remain mostly intact but (2) get mushy from the lengthy cooking.

Of course, people can enjoy whatever the hell they enjoy. This is a culinary disagreement, not an ethical one. I just think that no matter what flavor you want, the texture could be improved by going a little deeper in what’s already out there.

And for our money? Our congee-texture-aesthetic-ideal is a Shunde style called Shenggunzhou. It’s a style that’s famed throughout the Pearl River Delta, a corner of the country that itself it famed for its congees. It’s neither thin, nor thick. It’s smooth, creamy, with rice grains that’re broken down enough to make a cohesive whole, but still barely intact (to avoid pastiness).

It’s a fantastic congee, and has the benefit of being infinitely tweakable and adjustable.

It’s also… pretty easy, actually.

The Key to Shunde-style Congee

So if you’re familiar at all with Cantonese food, you might assume that something viewed as a congee ideal in the Cantonese world would probably involve some sort of… crazy time-intensive technique.

But it actually doesn’t. On the contrary, it relies on one of the most humble rices you could possibly reach for: broken rice.

For the unaware, broken rice is basically what it says on the tin: rice that’s somehow been damaged in storage or transport. Traditionally, it made for a lower grade of rice consumed by the working class, but over time people began to realize that it made for a pretty fantastic congee. One of the keys to a creamy Cantonese congee is for the rice grains to jumble around in the pot (at times next to something like a big pork bone to create more “surface area for jumbling opportunities”), to allow the rice to slightly break down while cooking.

Broken rice simplifies that process - with already broken rice, you can shave significant time off of your congee.

Of course, given that I doubt many of you have access to broken rice, in the recipe for the congee base below we’ll be breaking some rice from whole grains ourselves. That said, you might be able to find broken rice at a Vietnamese grocer, under the name “Gạo tấm” (a broken rice dish called Cơm tấm is a staple in South Vietnam). And of course, for those that happen to be China-based, broken rice is obviously also available as well under the name “米砂”, though you might need to purchase it online.

The Logic of a Shunde-style Congee

If you broke down the characters of “Shenggunzhou” (生滚粥), it would literally mean “raw boiled congee”. Why… ‘raw’?

Well, there’s going to be two broad strokes to a Shunde congee: the congee base (called the ‘粥底’) and the finishing, which’s when you’ll toss in your congee add-ins of choice. The reason it’s called ‘raw boiled’ is that you’re boiling the raw ingredients directly in the congee - contrasting with, say, century egg and pork congee where they’re cooked together with the rice from the beginning.

The goal of the base is to arrive at exactly the congee texture that you desire. From there, a restaurant would hold the base on the side until someone orders, at which time they’d finish it with their add-ins (sometimes even at the table - the specific heat capacity of congee is, uh, borderline dangerously impressive). At home, you can make your congee base early on in the cooking process, and finish it right before serving.

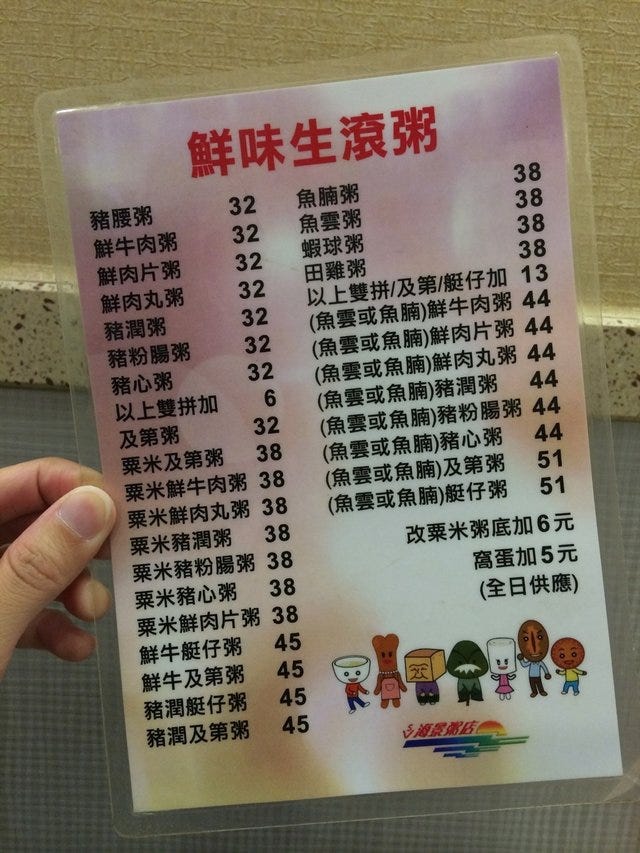

For the finishing, you can really add whatever you want, which’s where you really have some leeway to get creative. In Shunde, you can often see congee toppings take up an entire menu:

In this post, we’ll cover two classic toppings - sliced fish, and pork meatball. But to, I hope, give you a little confidence to get creative, we also whipped up a vaguely-carbonara-inspired congee with… Pancetta, Pecorino Romano, and a cracked egg. It’s a little unhinged (granted), but the end result was fun and tasty enough.

The Congee Base

Ingredients:

Jasmine rice (粘米/泰国香米) -or- Broken Rice (米沙), 80g

Marinade for the rice:

Salt, 1/4 tsp

Peanut oil, 1/4 tsp

Water, ~1.3L. We’ll be using 1 part rice to 16 parts water by weight. In the video we dutifully used 1.28L (an easier trick to pull with a scale), but you can use 1.3L like a normal person.

Ginger, ~1/2 cm. Crushed.

White pepper, ~1/4 tsp. Roughly crushed.

Dried scallop -or- dried shrimp, 5 -or- skip it. For a little base umami. If you don’t have easy access to these ingredients, you can hit similar notes by adding a touch of fish sauce into the final seasoning.

Process:

Rinse your rice. If you’re working from jasmine rice, first mix it with with the salt and peanut oil and let it sit for 20 minutes. After that time, gently crush the rice with a heavy mortar, a rolling pin, or a large beer bottle. You should be looking at something roughly like this.

If you’re working from broken rice directly, simply marinate it directly with the salt and oil, and begin the next step after 20 minutes.

To a pot, add in the water, the ginger, the white pepper, and the dried scallop/shrimp. Bring to a rapid boil, then sprinkle the marinated broken rice in. Swap the flame to medium, keeping the congee at a heavy simmer. Crack the lid with a chopstick to ensure that there’s a good crack (to prevent overflowing).

Boil for 30 minutes, or until good and creamy.

The Finishing

Option #1: Sliced Fish

Ingredients:

Fish fillet, 200g.

Marinade for the fish:

Salt, 1/4 tsp

White pepper, 1/4 tsp

MSG (味精), 1/4 tsp

Cornstarch (生粉), 1 tsp

Peanut oil, 1 tbsp

Final seasoning:

Crushed white pepper, 1/4 tsp

Salt, 1/4 tsp

MSG (味精), 1/8 tsp

Chicken bouillon powder (鸡粉), 1/4 tsp

Optional: fish sauce (鱼露), 1/4 tsp. If you didn’t add any dried scallop or dried shrimp (this is not seen in Shunde, but would taste good).

Chopped scallion and cilantro. To finish.

Process:

Slice the fish fillet on a bias into ~1/2 cm thick pieces. Mix with the marinade (coating with peanut oil at the end). Set aside.

Get your congee base up to a boil and add in the final seasoning. Slide the fish slices in, mix, and shut off the flame. The residual heat will continue to cook the fish. Top with a bit of chopped scallion and cilantro.

Option #2: Pork Meatballs

Ingredients:

Ground Pork Shoulder, 180g. Today we will be working from ground pork (not on-brand for us, I know). We have found that ground pork actually works okay for this sort of application so long as it came from a tougher cut like shoulder or collar. I know that ground pork is usually from a… mysterious… part of the pig at many supermarkets, so if you have neither (1) cooperative butcher nor (2) a meat grinder, we would suggest that you still mince by hand.

Optional: Dried wood ear mushrooms (木耳), 3. Reconstituted in cool water for ~60 minutes, then julienned.

Seasoning for the pork:

Salt, 1/4 tsp

White pepper, 1/8 tsp

MSG (味精), 1/8 tsp

Soy sauce (生抽), 1/4 tsp

Liaojiu a.k.a. Shaoxing wine (料酒/绍酒), 1/2 tsp

Cornstarch (生粉), 2 tsp

Peanut oil, 1/2 tbsp

Final seasoning:

Crushed white pepper, 1/4 tsp

Salt, 1/4 tsp

MSG (味精), 1/8 tsp

Chicken bouillon powder (鸡粉), 1/4 tsp

Optional: fish sauce (鱼露), 1/4 tsp. If you didn’t add any dried scallop or dried shrimp (this is not seen in Shunde, but would taste good).

Chopped scallion and cilantro. To finish.

Process:

If adding dried wood ear mushrooms, first reconstitute and slice them. Set aside.

Take the ground pork, and begin to vigorously chop it by hand. Your goal is to get the meat from a ‘grind’ to a ‘paste’. This should take 2-3 minutes. Transfer to a bowl.

Add in all of the seasoning except for the peanut oil. Stir the pork in one direction only for 2-3 minutes, or until it leaves streaks along the side of the bowl. Fold in the mushrooms, if using. Coat everything with the oil.

Get your congee base up to a boil, add in the seasoning, then swap the flame to low. Using a spoon (a Chinese soup spoon is perfect for this), shape the pork mixture into a rough ‘ball’ shape, then gently drop it into the congee. Work one by one until all the meat is in the pot. Bring it back to a boil for one minute to cook the meatballs and heat off.

Top with a bit of chopped scallion and cilantro.

Option, uh, #3: ‘Carbonara’ Congee

Even if you’re skeptical to hop on this train, this is still a solid chance to show you how to add a wodan - a cracked egg - into a congee.

Ingredients:

Pancetta, 25g. Thinly sliced. With the benefit of hindsight, I might actually go prosciutto next time.

Pecorino Romano, 30g. Or whatever similar cheese, grated.

Final seasoning:

Crushed white pepper, 1/4 tsp

Salt, 1/4 tsp

MSG (味精), 1/8 tsp

Chicken bouillon powder (鸡粉), 1/4 tsp

Optional: fish sauce (鱼露), 1/4 tsp. If you didn’t add any dried scallop or dried shrimp (this is not seen in Shunde, but would taste good).

Egg, 1. To crack into the congee.

Chopped scallion. To finish.

Process:

Thinly slice the pancetta (or prosciutto), grate the cheese.

Bring the congee base up to a boil, then add in the pancetta, the cheese, and the final seasoning. Crack an egg into the congee, then immediately shut off the heat - you’re not trying to poach the egg, just let the residual heat cook it through.

Transfer to a bowl (the egg will slide up to the top), and sprinkle over the sliced scallion.

Making this congee even easier

So right. One cool thing about this whole approach?

That marinated broken rice is… freezable. So if you want your congee fast (and who doesn’t in the morning), you can scale up, make a big batch, and then portion that rice into little baggies to go in the freezer.

Then when you want your congee? There’s no need to thaw or anything, just sprinkle it into the boiling water just like the above recipe, cooking it for the prescribed 30 minutes. You might even get away with shaving off a couple minutes, as the frozen rice actually breaks down faster.

So… possible avenues to get creative?

Our carbonara-inspired congee was pretty good (Parmesan cheese is pretty awesome in a congee actually), but despite the obviously-risotto-inspired congees I see out there, I can’t help but think that pasta sauce inspirations might be a little bit of a dead end. To my imaginary taste buds at least, I feel like there’s way more pasta dishes that wouldn’t work than those that would.

In hindsight, I think the world of thick soups could’ve been a decent avenue to explore. Stuff like cream soups, bisques, chowders, etc etc. Like, a potential ‘Lobster Bisque Congee’ makes… a lot of sense to me. There could also be a practical element to congeeification as well, as it would allow you to cut back on the cream, avoid having to puree things, and potentially even make it a bit more of a ‘main dish’ (though you’d probably want to serve alongside crusty bread or Youtiao fried dough sticks).

Fantastic video! Tried the recipe but still confused why my congee didn't end up with that milky white appearance. Mine appeared more translucent/ gluggier? I used jasmine rice and made sure to rinse it thoroughly prior to cooking. Would cooking it longer give me this result? Or potentially my pot was too wide for the amount of rice/water I was using? 3/4 cup rice : 12 cups water? I've seen some of the congee pots have a rounded narrower base and tall dimensions? Does this increase the changes of the rice grains smashing into eachother when boiling?

Do you have any suggestions for batch cooking the topping? Can you freeze the sliced marinated fish? Pre-cook it and freeze it? We love congee for breakfast but are trying to make it 5 minutes in the microwave max each day, with some batch cooking each week.