As a home cook, I’ve always hated what I call ‘nested’ recipes.

You know the sort —open up some cookbooks, and it’s like a damn matryoshka doll: recipes needing a spice blend given at page 6, a prepped sauce from page 35, which in turn uses a stock from page 12.

Of course, there’s a reason these cookbooks are doing what they do — pre-prepared, batch-prepped ingredients can obviously be useful. If you’re making Thai food on the regular, having an excellent homemade curry paste in your fridge is certainly going to be a useful trick up your sleeve. But the reality of many modern food lovers is that a lot of us find ourselves making a Chowder on Thursday, a Massaman Curry on Friday, Sichuan Boiled fish on Saturday, and a Ragu on Sunday. Multi-culturalism… has spoiled us.

Now, our recipes here tend to aim for cultural fidelity, so admittedly not many could be described as ‘quick and easy’ or ‘dinner in 20 minutes’. But nested recipes? That’s where I’ve chosen to draw the line.

And frankly, maybe that’s sometimes made covering certain Sichuan dishes a little awkward.

‘Sichuan food’ (as most people know it) came from the 90s

A lot of what people today understand as ‘Sichuan food’ is very much a modern restaurant phenomenon.

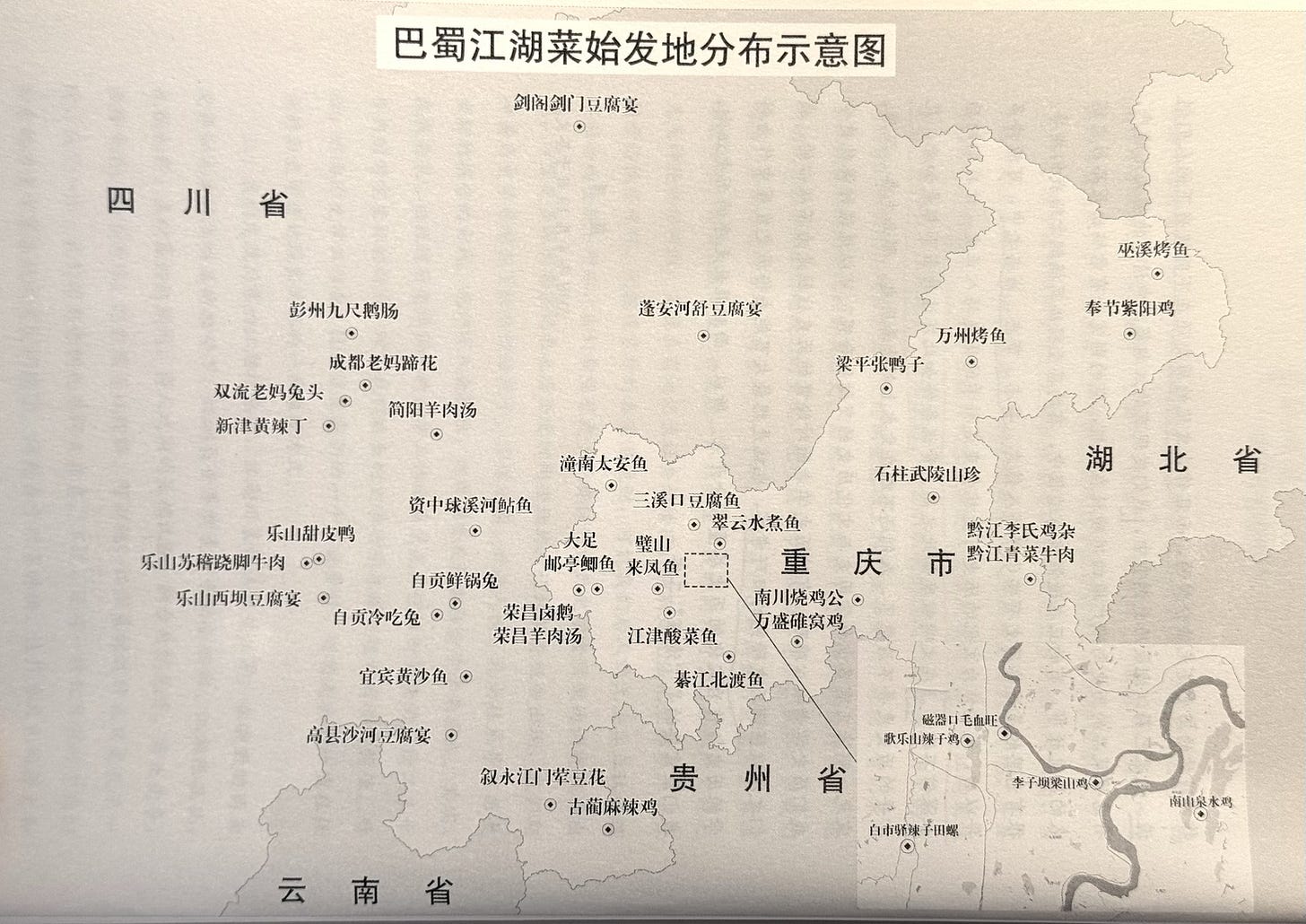

And that phenomenon, in turn, can’t really be grappled with without understanding a category of Sichuan food called Jianghucai (江湖菜) — a genre of restaurant that simply exploded in and around the region in the 1990s.

The literal translation of Jianghucai is “river and lake food”. The “river” and “lake” here doesn’t actually refer to literal ‘rivers’ and ‘lakes’, but rather to a sort of… general kind of rural, backwoods hinterlands. It’s a somewhat romantic term that’s very much evocative of the wilderness, and came to describe certain restaurants that began to pop up in villages outside of cities and along the old highway system, feeding both hungry truckers and urban weekenders looking for a tasty meal.

Similar restaurants scenes can be seen throughout China (in Guangdong, they’re referred to as nongzhuang; in Yunnan, nongjiale). Seeing how such restaurants need to entice people from the city, traditionally they’d often attempt to one each other up not just on the axis of ‘deliciousness’, but also with bold concepts and flashy dishes. Think meme food, but actually good:

And in Sichuan/Chongqing, they would also apparently compete on flavor.

Because “Jianghu”, it doesn’t just refer to the physical wilderness: it equally refers to the incorporeal wilderness. The antonym of the Jianghu is Miaotang (庙堂) — “temple and court” — itself shorthand for Confucian urbanized society, and its civilized, genteel, top-down power structures. The Miaotang is Civilization; the Jianghu is The Frontier. And so, the Jianghu can also describe the rough, the untamed — the lawless, the free.

And culinarily? It’s a pretty good way to describe the sheer audacity of the dishes that were being forged in these restaurants.

Take Laziji — Sichuan Spicy Chicken — as an example. The twin progenitors of the dish, Linzhongle (林中乐) and Chunshanju (春山居), were from the town of Geleshan right outside of Chongqing. Laziji (“Sichuan Spicy Chicken”). For those unfamiliar with the chicken, below is a nice food-travel vlog from the esteemed Wang Gang traveling to the original locations. Of course, Sichuan cuisine has never been no stranger to the chili pepper, but back in the early 90s these two restaurants pushed things to a borderline comical degree: a spicy chicken with so many chilis that today the thing is sometimes jokingly called ‘hide and seek chicken’.

But that’s just Jianghucai. It’s bold as fuck. More chilis, more spices, more oil, more aromatics, more… everything. Dial the spicyness up, dial the numbingness up — a coordinated assault that leaves the taste receptors in a state of shock and awe. It spread through the roads, it spread through the truck stops. Perhaps a surprising number of what we think of as classic Sichuan dishes had these modern, wild roots:

And perhaps the story of the Lazijis of the world might have stopped there — a much beloved, albeit somewhat niche, local dish along lines of Cantonese Sauna Chicken.

But this Jianghu explosion? It happened concurrently with another explosion in the Chinese F&B industry: the torrid growth of Sichuanese restaurants outside of Sichuan.

It’s a well-trodden tale that in the early years of China’s reform and opening, migrants from the interior streamed to the coast to look for work and opportunity — of which, the Sichuanese were certainly among the most numerous. This by itself probably would’ve been enough to give rise to a lively food scene across the country (I mean, there’s some fantastic Dominican food around Pennsylvania these days). ‘Delicious’ has a way of flowing downhill.

But Sichuan food was also given another important boost: the province’s local culinary associations. These associations published recipes for aspiring restauranteurs, they standardized training, they networked chefs. In some parts of China, recipes can be jealously guarded as a sort of ‘familial intellectual property’ — Sichuan’s concerted openness led to a situation where the Sichuan restaurant became an ecosystem that could be bought into. Not quite a turn key operation, but almost. In China, if you’re someone with a little bit of money, a desire to open a restaurant, and no direct F&B experience, you have two logical not-hotpot paths to follow: the Cantonese restaurant, and the Sichuan restaurant.

But these Sichuan restaurants outside of Sichuan? They’re sort of a geographic hodgepodge. Within Sichuan itself there’s a solid degree of regionality, but these restaurants grabbed dishes from everywhere — Mapo Tofu from Chengdu, Burning Noodles from Yibin, ‘Old’ Hotpot from Chongqing. But above all, they borrowed from that 90s-era Jianghucai explosion: ‘Boiled’ fish, ‘Boiled’ beef, Fresh Chili Rabbit, Beer Duck, Suan Cai Yu ‘Sauerkraut’ fish, Wanzhou Spicy Grilled Fish… among others.

The end result is regional cuisine that’s quickly becoming a national one — you can find a jianghucai-laden modern Sichuan restaurant in practically every decently sized town across all the four corners of the country. And internationally, it appears this sort of fare is becoming increasingly synonymous with not just Sichuan food, but Chinese food in general. Partially to the chagrin of us Cantonese food enthusiasts, it seems people are beginning to reflexively associate ‘authentic Chinese food’ with ‘bold chili-laded flavors’. And while that, at times, might make my eye twitch a bit… what’s undeniable is that nobody does ‘spicy’ quite like Jianghucai does.

Your desire to learn Sichuan food, in all probability, came from your eating at a Sichuan restaurant. You loved it, and you wanted to recreate those flavors at home.

So, let’s talk about how you can make some of those flavors.

Understanding How Restaurants are Different

It’s important to remember that restaurant operations, the world over, tend to lean heavily on batch-prepped components and ingredients. It’s the core operational logic, seen everywhere from Escoffier’s mother sauces to the Cantonese wok station. Chinese restaurants get tasty food to your table quick not solely because of their high powered burners (though that doesn’t hurt), but because much of the cooking was actually done well before service.

Ultimately, what a restaurant batch-preps will depend on their menu. Suppose you were running a restaurant operation specializing in Sichuan Suan Cai Yu, ‘Sauerkraut’ Fish. We shared a recipe a good while back for how to make the thing at home:

I won’t make you watch the video. The basic logic of the dish is:

Fillet a fish

Thinly slice the fillet and marinate it with a starch-heavy coating

Make a milky fish stock with the bones

Fry some aromatics together with minced pickled mustard green, chilis, and ginger

Add back the stock, poach the fish for a couple minutes

Finish with a quick chili oil

If this is your specialty, you’d obviously want to batch-prep a whole bunch of milky fish stock. But something else you could have sitting around pre-made might be an oil infused with both aromatics and that spate of fried pickles. You could also perhaps have the finishing chili oil prepped.

Then, when someone orders, all you’d need to do is (1) slice and marinate the fish (2) heat up the oil base and add the stock (3) poach the fish, drizzling with your prepped chili oil.

What Home Cooked Recreations Are Missing

Home cooking is, of course, a very different logistics. You aren’t churning through dozens of orders of Suan Cai Yu every day of the week: you’re making it once or twice and moving on to the next thing. It’s okay to start off a recipe leisurely frying some aromatics — that’s why god invented beer and audiobooks.

For example, many Sichuan restaurants will likely have something called ‘ginger-scallion water’ (姜葱水) pre-prepared. All this is, really, is an infusion of crushed ginger and scallion in with hot, boiled water, which is then used in marinades and to a lesser extent sauces. At home, if we really wanted to include the stuff in a recipe (often it can be omitted), you can simply just make it on the spot when you need it — waiting ~30 minutes for ginger-scallion water to be done soaking isn’t the end of the world, and is certainly preferable to juggling something else that could easily spoil in the fridge.

This is why I sort of hate nested recipes: they often seem willfully ignorant of the realities of a home kitchen. Untangling the ‘restaurant stack’ for you, I think, is something fundamental to the job of a recipe writer.

But in avoiding the stack, when it comes to restaurant-style Sichuan dishes, we do lose something subtle. There are two things that a modern Sichuan restaurant would have pre-prepped that absolutely do move the needle, flavor-wise:

Stock

Chili Oils

Stock is somewhat self-explanatory. But when it comes to chili oil, many of the oils employed in a modern Sichuan restaurant are actually rather complex infusions — infusions that ‘quick splash of oil over chili flakes’ or ‘Lao Gan Ma with a couple adjustments’ don’t quite reach the heights of.

But if you commit to keeping these two things on hand? I hesitate to employ the cooking influencer cliche of ‘leveling up’, but the game world will… definitely begin to open up a bit.

Stock

You know the drill by now. Doesn’t matter the cuisine: recipe writer lecturing you on making a homemade stock is roughly as old of a news story as a dental hygienist lecturing you on the virtues of flossing.

To reiterate, boxed stock from the supermarket is simply not good. It’s functionally water, bouillon powder, too much salt, and (in the west) loads of potentially irrelevant flavors like thyme to try to distract you from the above facts. Even straight up bouillon powder is usually a better option. In the west, there’re a couple concentrates like Better-than-Bouillon that’re really quite solid, but unfortunately Chinese food doesn’t really have something similar on the market. However, Chinese food fortunately tends to lean on fermented sauces (e.g. soy sauce, chili bean paste) for depth, so home cooks can usually get away with just chucking in a bit of chicken bouillon powder and calling it a day.

But a good stock will certainly still move the needle. Even in chili-laced dishes, a few spoonfuls will give things a certain complexity and ‘oomph’. To make a Chinese-style stock you have two options: you can make basic (usually pork) bone stock, or you can follow the classical Chinese system of stock making. A small eatery would use the former, a higher end restaurant might perhaps lean towards do the latter.

To make a basic Chinese-style pork bone stock is relatively straightforward.

Basic Pork Bone Stock

To a pot of cool water, add:

600g pork bones (with some meat still attached, or a mix of pork ribs and pork bones)

and bring it up to a boil. Boil for two minutes, and strain.

In a new pot, add:

4L cool water

The blanched pork bones from above

1.5 tbsp Shaoxing wine

~1.5 inch ginger, smashed

~2 scallions, tied in a knot

Bring to a boil, skimming if you need. Swap the flame to low and simmer for at least three hours, or up to six.

Classical Chinese Stock

For a fancier stock, we discussed this before in our — quite old, apologies — video on stock making. The information in said video had a Cantonese focus, but it rhymes with the Sichuan tradition (both are ultimately derived from Shandong):

The fundamental idea of these stocks is to first make a very intense, meat-heavy soup that can be employed in the fanciest dishes — this is sometimes called ‘gaotang’ (高汤) or ‘shangtang’ (上汤). For a more general purpose stock, there are two options: (1) you can add water to the same ingredients again, extracting another round out of it (called 二汤 or ‘second stock’ in a Cantonese context) and/or (2) cutting the fancy stock with water (a bit more relevant for homecooks, I feel).

The information in the above video was presented awkwardly (it’s an old video), but the recipes will get you close to a restaurant style stock. That said, over the years I’ve honed by own personal approach to making a Gaotang, which’s proved a little more relevant to my personal kitchen:

Chris’s Gaotang

Separate

2.5-3 kg chicken

into the carcass, thighs, wings, feet, the chicken fat, and breast. Set the fat and the breast aside. To make the stock, add everything else to a pot with

500g lean pork, cut into large chunks

~1.5 tbsp Shaoxing wine (料酒/绍酒)

100g duck feet (optional)

and bring up to a rapid boil. Boil for ~1 minute, then pour out the liquid and quickly rinse the meat. Add:

~4L filtered water (enough to thoroughly submerge)

50g non-smoked cured dried ham, e.g. Jinhua ham, Xuanwei ham, Prosciutto, Smithfield ham (optional but recommended)

~2 inches ginger, smashed

And bring up to a boil then down to a heavy simmer, skimming if you need.

At the 90 minute mark, remove the thighs and reserve for another use1. Simmer for 4 more hours, for 5.5 hours total. Strain into a large bowl, leave the stock overnight in the fridge.

Skim the fat off of the stock. This fat can be combined with the fat of the chicken and rendered into schmaltz.

Transfer, then freeze the stock. Small water bottles, plastic travel bottles, or ice cube trays are all solid candidates (we’ve recently swapped to disposable ice cube bag like this, which are perfect).

If I am using the stock in a sauce (i.e. something measured in tablespoons), I will use the stock directly. If using in a soup, mix one part stock with two parts water (or equal parts if you’d like to be a bit more generous), and season with chicken bouillon powder.

Chili Oils

Stock is ubiquitous to many cuisines, but I think the chili oils are what truly differentiate the modern Sichuan restaurant.

You could maybe think of Sichuan chili oils in similar terms as Escoffier’s mother sauces: they can be plugged into a number of different dishes, forming the foundation of some and the finishing touches of others. And just like the French mother sauces, some are oils are undeniably more common than others (and a home cook would likely only make one or two of them).

Hongyou (红油), red oil (also called youlazi), is by far the most common and (unlike some of the others) well predates The Jianghu Explosion in the 90s. If, in English, someone says to you the words “Sichuan Chili Oil”, this is what they’re describing. A home cook in Sichuan would likely also have Hongyou on hand — whether homemade, or purchased from the market.

Worth making at home? Yes. Hongyou is, unfortunately, a bit like stock in that the bottled variants are really not very good (many will use additives to amp up the heat). If you have ambitions of making Sichuan food on the regular, having something quality and homemade is worth keeping around.

Mala Hongyou (麻辣红油) is, you guessed it a Mala — numbing spicy — chili oil. It’ll both lean on a greater proportion of spicy chilis (more on that later), while also including a mouth-tingling quantity of Sichuan pepper in the mix. ‘Mala’ as a flavor profile similarly predates The Jianghu Explosion… but if there’s one flavor Jianghu food loves more than any, it’s undeniably Mala. If you’re a restaurant whipping out a number of Mala dishes, a specifically Mala chili oil can be a useful thing to have on hand.

Worth making at home? It depends. I personally would not make Mala Hongyou at home. If I’m aiming for something Mala, I would rather toast and grind Sichuan peppercorns for that specific dish, and have a more general purpose hongyou on hand.

Hotpot base (火锅底料) is derived from the beef hotpot tradition of the city of Chongqing. Similar to Mala Hongyou, it’s quite spicy and numbing, but unlike the above lean in Ciba Chili Paste (reconstituted-then-pounded dried chilis) instead of dried chili flakes. Further, hotpot base is made using beef tallow, includes Sichuan chili bean paste, and is often seasoned. It’s used as a base for spicy hotpot (of course), but it can also be a convenient ‘instant start’ for various dishes. Quality hotpot bases can be available for purchase, so these are often be purchased from a vender — unless a restaurant specializes in hotpot.

Worth making at home? Probably not, mostly because there are some very good packages of Sichuan hotpot bases that are available for purchase. It can be very useful to have some on hand however, so if you do not have anything good at your local Chinese or Asian supermarket, do check out Wang Gang’s excellent recipe on the topic.

Laoyou (老油), i.e. “old oil” is comes pretty directly from the flavors employed in hotpot bases — the name itself a reference to “Chongqing Old Hotpot” (重庆老火锅). Laoyou is in some ways an adjusted Hot Pot base, made a bit more general-purpose. It opts for oil instead of tallow, and seasons everything a bit less aggressively. It can function as an ‘instant start’ for various stir fries such as Twice Cooked Pork or Homestyle Tofu.

Worth making at home? For us, yes. We didn’t used to have this around before testing this video… but as soon as we run out, we’re making more. It’s an incredibly convenient stir fry base.

Dry pot base (干锅酱) is technically categorized as a ‘sauce’ (酱), but is worth mentioning as it is a seasoned mix of Laoyou and Hotpot base. This can form the foundation of various sizzling ‘dry pot’ dishes.

Worth making at home? I would personally probably mix up a dry pot base the day of… but if you’re in the market for a spicy stir fry base, this could be a convenient thing to have already-whipped-up.

Pickled Chili Oil (泡椒油) could perhaps be thought of as an extension of laoyou, leaning on finely minced pickled chilis instead Ciba chili paste. Some recipes will even include chili bean paste as well. It functions as an ‘instant start’ for dishes in the pickled chili or fish-fragrant flavor profile, such as Pickled Chili Kidney and Fish-Fragrant Eggplant.

Worth making at home? For us, yes (although to a lesser extent than hongyou and laoyou). It should be noted that this oil contains ingredients that may be impossible to source outside of China, so your personal mileage may with the thing may end up varying.

Fresh Chili Oil (鲜椒油) is an oil that’s specific to the fresh chili flavor profile of the city of Zigong and its environs, forming the foundations of dishes like Fresh Chili Rabbit and Fresh Chili Beef Noodle Soup.

Worth making at home? Probably not. It is, admittedly, by far the least common oil on this list, and would only be seen in restaurants that specialize in the above dishes. Also — unlike the above chili oils — this oil would not be able to keep very long.

Prepared Chili Products

Besides this, a restaurant may reach for three sorts of ‘prepared chilis’.

Knife Cut Chilis (刀口辣椒) are a mix of chilis and Sichuan peppercorns that are deep fried until fragrant, than chopped up with a knife. This will form a very coarse, very fragrant chili flake that can be used in various dishes.

Worth making at home? Probably not. Knife cut chilis are great, but making them is… a mess. Chilis and Sichuan pepper fly everywhere. If you’re clean freaks like us, it’s a total nightmare. If I needed, I’d reach for a mortar.

Scorched Chilis (煳辣壳) are chilis that are deep fried until almost past done, to a deep chestnut color. They can be used directly, or they can be ground into a coarse flake.

Worth making at home? Probably not, as the following (the chili oil variant) would keep moisture a bit better in a home cook’s fridge.

Scorched Chili Oil (煳辣椒油) is a somewhat less common implementation of scorched chilis, whereby the chilis are deep fried together with Sichuan pepper in an aromatics-infused oil, and left to soak inside.

Worth making at home? For us, yes — though at a priority level below hongyou and laoyou, and around pickled chili oil. This oil can help form the foundation of some very good Kung Pao dishes (what can I say? I’m a sucker for Kung Pao), and can also be added on a whim when you need a small handful of chilis in a stir fry (e.g. hand shredded cabbage). It’s also a nice finishing oil.

How to Make any Chili Oil: Sourcing

At the core of any chili oil is (1) chilis and (2) oil. Take a peek at historical recipes for chili oil in Sichuan, and a lot of them are basically chili flakes submerged in sizzling oil and… that’s pretty much it.

Nowadays, there tends to be a whole host of aromatics and spices in the mix. These are nice, but they’re ultimately optional in the end. If your chili peppers aren’t delicious? If your oil isn’t delicious? It’s simply… not going to be a great chili oil.

For the chili peppers themselves, most Sichuan chefs will lean on a blend. Generally speaking, this is will be (1) Zidantou bullet chili (子弹头) for fragrance, Erjingtiao (二荆条) two vixen chili for color, and Xiaomila (小米辣) millet chili for heat:

These three are local cultivars that’re really quite difficult to find outside of China, but that’s okay. You don’t need the specific chili peppers above, you need to understand the logic of why they were selected.

Fragrance

The word ‘fragrant’, I think, can be kind of abstract in English. It’s often associated with incredibly subtle flavors — the sort you bump into in wine, fine dining, etc. So, pop quiz: which of the below chili peppers are “fragrant” ones (note: Prik Kee Noo is the Thai name for what’s commonly thought of as ‘Thai Bird’s Eye’)?

…unless you’re a committed chili-head, I think the answer there isn’t necessarily obvious.

But ‘smell’ is obviously connected to ‘taste’, so if the concept of “chili fragrance” is confusing to you, think in terms of taste.

At the base of your chili oil, you’ll want the best tasting, best quality dried red chili that you have available to you. For the purposes of these recipes, this is going to be your workhorse chili pepper. Ideally, your dried chili should be (1) fresh enough that it’s still somewhat pliable and (2) something roughly medium-spicy (if you don’t want to have to make too many adjustments).

I, unfortunately, do not know what exactly you have local to you — in the end, the burden of figuring this out will have to be on you. But I can give you some ideas, based on my personal experience:

In America I like to use Mexican Guajillo chilis. They’re fantastically red and have a great fragrance. They’re slightly milder than many Sichuan chilis, but still end up taking me where I want to go.

Here, in Yunnan (and testing the below recipes) I’ll use either Guizhou Xianjiao (the cultivar Lao Gan Ma uses for its chili crisp) or Sichuan Erjingtiao.

When we were living in Bangkok I wasn’t super content with the profiles of any of the chili peppers on offer. The most fragrant Thai chili pepper is the aforementioned Prik Kee Noo, Thai Bird’s eye, which is… spicy as fuck (and probably one of the reasons why Thai food is among the spiciest in the world). Not ideal to base a chili oil around, so we would actually ship Erjingtiao down to Thailand from Sichuan. Something else I did a handful of times was strip my blend down to solely the ‘color’ and ‘heat’ components, which is an option in a pinch.

Now, I’ve never been to Europe, but the same logic applies. Off the top of my head, Aleppo Pepper seems like an obvious candidate, but perhaps you might find a nice source on something from Hungary or Calabria. Just… try to start with quality.

At the same time however, I also want to emphasize: I’m not a snob. Simply do the best you can. I know that for the London-based Fuchsia Dunlop, she bases everything off of Korean Gochugaru in her chili oil recipes. If that’s the best you can do, that’s the best you can do!

Some of these chili peppers (like the Korean sort) may be somewhat milder that Sichuan chilis, but that’s also okay.

You can compensate.

Heat

Because making a chili oil spicier? It really isn’t rocket science.

All you need to do is cut your fragrant, workhorse chili pepper with enough of a spicy chili to get the thing up to your personal tolerance level. The oil should be spicy enough to be somewhat uncomfortable if you ate it directly with a spoon.

Again, Sichuan chefs use Xiaomila millet chili for this function, and that’s what we tested with in the below recipes.

In America I’ve used bags of “Thai chilis”. These may or may not actually be from Thailand, and seem to correspond with a cultivar in Thailand known as Prik Jin (i.e. “Chinese chili”, fun!). This might (?) be the same thing as Tientsin Chilis, which I’ve also used before. One day I would like to try using Mexican chilis for this purpose, but spicy chilis such as Habanero appear to be most common in fresh (not dried) form. Unfortunately Arbols are somewhat on the mild side if explicitly being employed for heat.

When we were living in Bangkok, I would either use the aforementioned Prik Jin or purchase dried Thai Bird’s Eye, Prik Kee Noo, online (this chili pepper is fantastic, but in Bangkok usually only available fresh).

Whatever route you go, your quality demands will be much lower here than with your ‘fragrant’ chili. Not pliable? No problem — you’re solely looking for heat. Worst comes to worst, you might even be able to play around with a superhot (though obviously you would want to drastically cut down on the quantities we list below).

Just don’t be gross and reach for something like a Capsaicin extract, otherwise you might as well just get a bottled hongyou.

Color

You want your chili oil to be red, which is also not exactly rocket science.

There are certain cultivars of chili out there that are extremely red — some of them, practically neon. I mean, there’s a reason why the chili pepper is sometimes used as a dye. These types of chilis tend to be on the milder side: Korean gochugaru might be an obvious example.

In Sichuan… they’re spoiled. They actually use the aforementioned Erjingtiao for this function: sometimes chefs will refer to Erjingtiao as being for ‘both color and fragrance’. For me personally, I like my chili oil quite red… so I like to add in Kashmiri chili peppers from Xinjiang (which are a chili of the borderline-neon variety).

In America, I like Gochugaru. Widely available, does the trick, tastes alright.

When we were living in Bangkok, I would use a chili called ‘big chili’2, it’s the sort that would go in the Nam Prik Pao chili jam — the foundational sauce for stuff like Shrimp Tom Yum.

For this function, you might even be able to get away with a quality sweet paprika as well (and by “quality” I mean something with a nice vibrant shade of red… not the bottle of McCormick’s that’s been in the back of your parent’s spice cabinet since the Clinton administration).

Oil

In Sichuan, for a good chili oil, there is no choice but caiziyou.

We’ve discussed caiziyou on the channel before — what the stuff is is an unprocessed (i.e., not RBD3), expeller-pressed rapeseed oil made from a specific Chinese cultivar called semi-winter rape:

The oil has a number of advantages. First, it’s not some sort of processed neutral oil. The stuff actually tastes really good (I’m shit at describing tastes, but let’s call it “nutty with a note of hay?”).

Second, it’s quite viscous. The thickness of it is perfect for cold dishes and other applications where you really want the oil to cling to the ingredient, as well as the mouth of the eater. Yet at the same time, unlike lard, tallow, or palm oil… it remains liquid at room temperature, which gives you a lot more optionality to work across various dishes.

The bad news, however, is that Caiziyou is infamously, brutally difficult to find outside of China. Last time I was in Philadelphia I could find a bottle, but that very much seems to be an exceptional case. Don’t pull your hair out scouting for the stuff — there are substitutes.

The very best substitute, if you can find it, is Indian Mustard Seed Oil. It’s got a slight mustard-y nose hit to it, but that’ll mellow out after bringing it all up to smoke point (and is not wholly unpleasant in the context of a chili oil). When buying — in the US, at least — it’s sold with the label ‘for external use only’, though the ingredient list should be something along the lines of ‘100% mustard seed’. We go into why in the above video (long story, the FDA slapped it on because of “health concerns” from back in the 50s, so… don’t narc on your Indian grocer, if anyone asks it’s all for your traditional Bengali massage).

Besides that, at Chinese grocers in the west you can often find unprocessed peanut oil. It's an oil that’s commonly used in Cantonese cooking: it smells like peanuts, tastes great, but it unfortunately doesn’t quite have the same viscosity as caiziyou or Indian mustard seed oil.

Another route, however, that we also tried testing — and stay with me here — was the thick, unprocessed oil traditional to the western cooking tradition:

…and it actually really worked.

The Italians will yell at us, I assume, for bringing the oil up past smoke point. Pay no heed to the Italians. It’ll indeed impart a bitterness to the oil (I mean, the Italians aren’t crazy), but only on the first day — the bitterness will fade completely after sitting for 24-48 hours, as is standard practice when making Sichuan chili oil. You might assume that the flavor of olive oil would clash with Sichuan flavors, and it’s certainly true that my nose and brain were thoroughly confused when cooking up the stuff. But the high temperature, combined with the sheer quantity of aromatics and chilis, really tamps back on that ‘olive oil’ flavor. And, of course, it’s got a fantastic viscosity to it.

I should emphasize, however, that olive oil would not be appropriate as a general Sichuan cooking oil. For stir frying, lard or peanut oil would be much better choices for the caiziyou-less. Olive oil only works for chili oil.

And lastly, I should note again that we don’t want to be snobs here. If all you can get is a neutral oil, use a neutral oil. We’ll be infusing it all with aromatics anyhow, so it’s not the end of the world or anything.

So… check out your local grocers, see what’s online, and make your selections:

…and let’s make some chili oil.

A Quick Note on the Below Recipes

The Sichuan chili oils below were all thoroughly tested, and the accompanying instructional video can, of course, be found at the top of this post.

We wanted to pair this with recipes for how to use these chili oils up, as — with the exception of Hongyou — we will likely not be calling for them in any future recipes. I do, after all, still hate nested recipes. These ‘accompanying recipes’ are not as thoroughly tested as what is in our videos, often only cooked once or twice. The picture’s just a quick snap of the final result from our cell phone camera (do forgive us for not breaking out the DSLR).

After making this video, we have… a lot of chili oils to work through. As we work through them, we’ll be updating this post with more recipes that we’ve enjoyed. A good chunk of these recipes are simple translations/adaptations from some of our collection of Chinese cookbooks — if this is the case, we’ll note the source above the recipe.

Hongyou, Sichuan Red Chili Oil

Note: Our chili mix here was 60% of our fragrant chili (Erjingtiao), 30% of our red chili (Kashmiri), and 10% of the spicy chili (Xiaomila).

For our red chili — the Kashmiri from Xinjiang — at our local market this came in powder form. We will be adding this chili powder later in the process, as powders sometimes like to burn at high temperatures. If you are using whole chili peppers (ideal!), handle them as we do the fragrant/spicy chilis below.

Slice

60g fragrant chili pepper (e.g. Erjingtiao, Zidantou, Guajillo, Aleppo)

10g spicy chili pepper (e.g. Xiaomila, Thai Bird’s Eye, Tientsin)

into roughly 2 inch sections, tossing the stem.

Add the chilis to a wok or cast iron dutch oven together with ~1 tbsp of oil. Fry the chilis until they begin to get brittle — roughly 2-6 minutes, depending on how fresh the chilis are.

In a mortar, pound into a fine flake, roughly the size of a sesame seed. A blender or food processor may also be used, but be careful not to ‘overcook’ the chilis4. Add to a large bowl, and mix with

1.5 tbsp sesame seeds

and reserve.

In a wok, add

2 cups oil (e.g. Caiziyou, Mustard Seed, Peanut, or Olive)

½ onion, finely sliced

~5 scallions, chopped

~2 inches ginger, smashed

and fry over a medium flame. After about ten minutes, wet the following spices with a bit of strong liquor, e.g. baijiu or vodka. Any spices that you cannot find may be omitted:

3 dried bay leaves (香叶)

3 slices or ~2g sand ginger (沙姜)5

1 Tsaoko (草果), Chinese black cardamom, peel only6

1 tbsp Sichuan Peppercorn (花椒)

2 star anise (八角)

~⅓ Cinnamon stick (桂皮)

½ tsp Fennel Seed (小茴香)

Add the spices into the bubbling oil, and continue to cook until the onions are golden brown, 8-10 minutes more. Strain, returning the oil to the wok7.

Heat the oil up past smoking, or ~190C. Shut off the heat. Ladle ~⅓ of a cup of hot oil into the bowl of chili flakes and sesame seeds, stirring vigorously. Then add

30g red chili powder (e.g. Kashmiri, Gochugaru)

into the bowl of chili flakes and sesame seeds, and mix very well.

Once the oil has cooled to ~150C, add roughly half of the remaining oil into the bowl of chili flakes and mix well. Allow the oil to cool to ~80C, then repeat with the remaining oil.

Cover, and let sit for at least 24 hours, and up to 48. Store in an airtight jar, preferably in the fridge. The chili oil should last about three months.

Recipes Using Hongyou

Dressing for Sichuan ‘Liangban’ Cold Dishes (a formula)

For every ~300g of ingredients, dress with the following sauce:

2 tbsp Hongyou, without sediment

1 tbsp Hongyou, with sediment

1 tbsp Light Soy Sauce (生抽)

1 tsp Dark Chinese vinegar (陈醋/镇江香醋/保宁醋)

1/4 tsp salt

1/2 tsp sugar

1/8 tsp MSG (味精)

Optional: 1/4 tsp Sichuan peppercorn powder (花椒粉)

This is particularly good together with a few cloves of minced garlic and a bit of cilantro. An example is below.

Liangban Cold Tofu Jerky with Celery (凉拌豆干)

Cut

200g Tofu Jerky (豆干)

100g Chinese Celery (西芹)

into 2-inch strips, and roughly the thickness of a chopstick. Then, roughly chop

1 stalk (~20g) cilantro

into half inch long pieces.

Mince

3 big cloves of garlic

and then roughly crush and chop

1 tbsp roasted, toasted, fried peanuts

into ~2mm large bits.

Then, in a wok, blanch the tofu jerky for about 1 minute, then add in the celery for another 30 seconds. Remove, and rinse cool with running water. Strain well.

In a big mixing bowl, add

2 tbsp Hongyou, without sediment

1 tbsp Hongyou, with sediment

1 tbsp Light Soy Sauce (生抽)

1 tsp Dark Chinese vinegar (陈醋/镇江香醋/保宁醋)

1/4 tsp salt

1/2 tsp sugar

1/8 tsp MSG (味精)

Optional: 1/4 tsp Sichuan peppercorn powder (花椒粉)

and mix with the blanched tofu jerky, the celery, the peanut, the garlic, and the cilantro.

Leshan MSG Noodles (味精素面)

We previously covered this dish before on the channel, you can refer to the video here for a visual.

Boil

150g fresh ramen noodle/alkaline noodle (拉面/鲜面/枧水面) -or- 100g dried egg/alkaline noodle (蛋面/枧水面)

until done, according to the package. Strain, but do not shock the noodles with cool water. Add to a bowl straight away with a sauce of

1 tbsp red chili oil, with sediment

1 tbsp Suimi Yacai, Sichuanese pickled and fermented mustard green (碎米芽菜/宜宾芽菜)

1 tsp light soy sauce (生抽)

¾ tsp MSG (味精)

½ tsp sugar

1 tbsp (10g) sliced scallions

Koushuiji, “Mouth Watering Chicken” (Chicken Breast Version)

This is another dish we’ve previously covered on the channel, many years back. That was a solid recipe — this version is my adaptation of the classic using (the easier to work with, admittedly) chicken breast. But because we’re opting for chicken breast, below we’ll actually be using a western technique for poaching the thing. Say what you will about the American culinary tradition, but it certainly has a lot of experience with chicken breast.

As such, the process for the breast below has been adapted from Dan Gritzer’s Serious Eats recipe here. Interestingly, there’s actually a lot of crossover between the traditional Chinese technique and the method he outlines, but I did basically go with his approach.

In a small pot, add

1 liter water

10g salt (~1/2 tbsp)

½ tsp chicken bouillon powder (optional)

Two small to medium chicken breast (~400g)

~2 inches ginger, smashed

~2 scallions, tied in a knot

1 tbsp Sichuan peppercorns

and slowly bring it up to ~70C. Hold the water at around 65-70C until the chicken breast reaches an internal temperature of 68C (~20-30 minutes), then remove. Pat dry and allow to cool down.

While the chicken is poaching, make a ginger-garlic water. To a bowl, add

1 inch ginger, smashed and roughly minced

1 large clove garlic, smashed and roughly minced

1 scallion, roughly minced

½ tbsp Sichuan peppercorns

¼ cup hot, boiled water from the kettle

and cover. Allow to steep for at least 30 minutes, then strain. We will need 3 tbsp for the final sauce:

3 tbsp ginger-garlic water from above

2 tbsp soy sauce

2 tsp sugar

¾ tsp dark Chinese vinegar

½ tsp Sichuan peppercorn powder

½ tsp MSG

¼ tsp chicken bouillon powder

¼ tsp salt

mix all the above very well, or until the sugar and salt completely dissolve. Then mix in:

5 tbsp hongyou sans sediment -or- mala hongyou from below -or- a combination as per your own tastes

2 tsp toasted sesame oil

Slice the now-cool chicken breast, then smother the sauce on.

Sprinkle liberally with toasted sesame seeds, and optionally garnish with some sliced scallion whites (ala the picture above).

Mala Hongyou, Sichuan Numbing-Spicy Red Chili Oil

Note: There are a couple of ways you can add Sichuan peppercorn to a chili oil. My preferred method would be to simply deep fry the Sichuan peppercorn until fragrant, and allow it to steep into the chili oil. The downside of this is that if you are using this together with the sediment, your dish will include whole Sichuan peppercorns.

This is a common pain among expatriates and travelers new to China, so instead we opted to made Sichuan peppercorn powder.

We will use a mix of red and green Sichuan peppercorn. The latter is more numbing. This mix can be swapped for solely 20g Red Sichuan Peppercorn if green are unavailable to you.

Toast

12g Red Sichuan peppercorn (花椒)

8g Green Sichuan peppercorn (青花椒)

in a dry wok or skillet over a medium low flame. After it leaves little oil splotches on the side of the wok, ~3 minutes, remove and grind into a powder. Mix the powder with

Half shot strong liquor, e.g. baijiu or vodka

and set aside.

Slice

70g fragrant chili pepper (e.g. Erjingtiao, Zidantou, Guajillo, Aleppo)

30g spicy chili pepper (e.g. Xiaomila, Thai Bird’s Eye, Tientsin)

into roughly 2 inch sections, tossing the stem.

Add the chilis to a wok or cast iron dutch oven together with ~1 tbsp of oil. Fry the chilis until they begin to get brittle — roughly 2-6 minutes, depending on how fresh the chilis are.

In a mortar, pound into a fine flake, roughly the size of a sesame seed. A blender or food processor may also be used, but be careful not to ‘overcook’ the chilis. Add to a large bowl, and mix with

1.5 tbsp sesame seeds

and reserve.

In a wok, add

2 cups oil (e.g. Caiziyou, Mustard Seed, Peanut, or Olive)

½ onion, finely sliced

~5 scallions, chopped

~2 inches ginger, smashed

and fry over a medium flame. After about ten minutes, wet the following spices with a bit of strong liquor, e.g. baijiu or vodka. Any spices that you cannot find may be omitted:

3 dried bay leaves (香叶)

3 slices or ~2g sand ginger (沙姜)

1 Tsaoko (草果), Chinese black cardamom, peel only

1 tbsp Sichuan Peppercorn (花椒)

2 star anise (八角)

~⅓ Cinnamon stick (桂皮)

½ tsp Fennel Seed (小茴香)

Add the spices into the bubbling oil, and continue to cook until the onions are golden brown, 8-10 minutes more. Strain, returning the oil to the wok.

Heat the oil up past smoking, or ~190C. Shut off the heat. Ladle ~⅓ of a cup of hot oil into the bowl of chili flakes and sesame seeds, stirring vigorously. Add the liquor-soaked Sichuan pepper powder to the bowl and mix well.

Once the oil has cooled to ~150C, add roughly half of the remaining oil into the bowl of chili flakes and mix well. Allow the oil to cool to ~80C, then repeat with the remaining oil.

Cover, and let sit for at least 24 hours, and up to 48. Store in an airtight jar, preferably in the fridge. The chili oil should last about three months.

Recipes Using Mala Hongyou

Mala Pork (麻辣肉片)

This is an old school Sichuan dish adapted from the cookbook “大众川菜”.

Separate the white part and the green part from

2 scallions

then slice the green bits and finely mincing the whites. Reserve.

Slice

225 pork shoulder

into thin 2-3mm sheets. Place in a bowl and add in

¼ tsp salt

¹⁄₁₆ tsp white pepper powder

¼ tsp soy sauce

⅛ tsp dark soy sauce

½ tsp Shaoxing wine

1 egg white

~1 tbsp cornstarch

~1 tbsp oil (optionally adding in bit of the mala chili oil)

and mix very well.

We will then pass the pork through oil. To do so, in a wok, heat roughly 1 cup of oil up to about 160 celsius. Add in the pork slices, and cook until they visually look ‘done’, ~45 seconds. Remove, strain, and dip the oil out of the pot.

Over a high flame, swirl in

2 tbsp lard

and then quickly stir fry

200g pea tips (豌豆尖) -or- spinach

until cooked, ~30 seconds, then season with

⅛ tsp salt

Place at the bottom of your serving plate. Evaluate your oil — add an additional 1-2 tbsp of lard if your vegetable absorbed most of it. Then over a low flame, slowly infuse that with

½ tbsp Pixian Doubanjiang, Sichuan Chili Bean Paste

and once the paste as stained the oil, add in

1 tbsp Mala Chili Oil, together with the sediment

and the minced scallion whites. Once those are fragrant, ~45 seconds, up your flame to high and add in the pork. Swirl in

½ tbsp Shaoxing wine

and after a quick mix, add in a sauce of:

60g stock, from above

1 tbsp soy sauce

½ tbsp cornstarch (or, preferably, a root vegetable starch like potato starch)

½ tsp sugar

¼ tsp chicken bouillon powder

¼ tsp MSG

Once thickened, swap the flame to low and drizzle over

1 tbsp of the Mala Chili Oil, without the sediment

and season to taste. I added in another

⅛ tsp salt

¼ tsp MSG

and mix in the sliced scallion greens. Serve over the pea tips/spinach.

Mala Hotpot Noodles

Note: The veg/mushroom/meatball/etc is completely up to you. This soup is a very good ‘fridge clean-up’ — just throw in whatever you want in the soup. For example, in the pictured pots we also added a bit of meat stuffed egg rolls and wontons.

Boil

100g dried egg/alkaline noodle (蛋面/面条/碱水面)

according to the package, until al dente. Strain and set aside. You could alternatively use instant noodles and skip this step.

Soak

10g kelp/konbu (干海带/昆布)

with hot water until softened, then strain.

Mince

1 clove garlic

½ inch ginger

and set aside.

Cut

60g napa cabbage (娃娃菜/黄芽白)

40g enoki or oyster mushroom (金针菇/秀珍菇)

1 stalk (20g) cilantro

and the reconstituted kelp from above into 1-2 inch long sections and set aside.

Prepare

150g of meat/meat products — your choice of frozen meat/fish balls, crab stick, fish tofu, spam, hot dog, or thinly sliced hot pot beef/pork (肉丸/午餐肉/火腿肠/火锅牛肉/火锅猪肉)

To a pot, heat on medium low, add in

2 tbsp Laoyou, with sediment (recipe below)

together with the minced garlic and ginger until fragrant, ~45 seconds. Then add in

1 cup stock

1.5 cups water

⅛ tsp salt

¼ tsp MSG (味精)

¼ tsp sugar

1 tsp soy sauce (生抽/酱油)

Add in the kelp and mushroom, bring to a boil and simmer for 3 minutes.

Add in napa cabbage and your choice of meatballs/spam/or hotdog. Cook for 2 minutes or until the meatballs/spam floats.

Add in the cooked noodles or instant noodles, cook for another minute to absorb flavor. If using thinly sliced hot pot meat, add in together with the noodles. When the noodle is done, shut off the heat. Finish with

1-2 tbsp (tolerance depending) of Mala chili oil, sediment included

and the chopped cilantro.

Laoyou, Sichuan ‘Old’ Chili Oil

Note: We decided to use all of our ‘fragrant’ workhorse chili pepper with this recipe, as we wanted to keep it a bit more general purpose. If you would like a spicier Laoyou, you can use 55-60g of your fragrant chili powder together with 10-15g of your spicy chili powder.

Slice

70g fragrant chili pepper (e.g. Erjingtiao, Zidantou, Guajillo, Aleppo)

into roughly 2 inch sections, tossing the stem. Place in a bowl and submerge with hot, boiled water from the kettle and cover.

After ~45 minutes, strain the chilis and roughly squeeze out the excess water. Add to a mortar, with an optional8

¼ tsp salt

1 clove garlic

and pound into a fine paste. You could also use a food processor. This is the Ciba Chili Paste — reserve.

Roughly mince

2 tbsp douchi (豆豉), Chinese fermented black soybeans

and wet with roughly a half shot of baijiu (or vodka). Set aside, then finely mince

¼ cup Pixian Doubanjiang, Sichuan Chili Bean Paste

and reserve.

In a wok, add

2 cups oil (e.g. Caiziyou, Mustard Seed, Peanut, or Olive)

½ onion, finely sliced

~5 scallions, chopped

~2 inches ginger, smashed

2 stalks Chinese celery (芹菜) -or- 1 stalk western celery (西芹), roughly chopped

2 sprigs cilantro, roughly chopped

and fry over a medium flame. After about ten minutes, wet the following spices with a bit of strong liquor, e.g. baijiu or vodka. Any spices that you cannot find may be omitted:

3 dried bay leaves (香叶)

3 slices or ~2g sand ginger (沙姜)

1 Tsaoko (草果), Chinese black cardamom, peel only

1 tbsp Sichuan Peppercorn (花椒)

2 star anise (八角)

~⅓ Cinnamon stick (桂皮)

½ tsp Fennel Seed (小茴香)

Add the spices into the bubbling oil, and continue to cook until the onions are golden brown, 8-10 minutes more. Strain, returning the oil to the wok.

With the flame off, add in the ciba chili paste and slowly fry over a medium-low flame. You want the paste to expel the moisture and stain the oil, and morph into a lighter (almost orange) hue, ~15 minutes. Strain the chilis, and reserve.

Then add the minced chili bean paste to the same oil and slow fry until dry. After ~3 minutes, add in the douchi. Once the moisture from the liquor’s evaporated off, ~2 minutes, shut off the heat. Add back the fried chili oil from before, and let the oil cool down. Transfer to a bowl, and let sit for at least 24 hours, and up to 48.

Store in an airtight jar, preferably in the fridge. The chili oil should last about three months.

Recipes Using Laoyou

Ganguo Dry Pot Base

This dry pot base could, perhaps, be thought of as a chili oil. We covered this before on the channel, under the video “The Big Stir Fry You’ve Always Wanted”, but the base in said video was very much a ‘de-nested’ approach. It will be a good visual for the dry pot itself, however (with the base in hand, feel free to jump in at 6:12 in said video).

The rule of thumb for a dry pot is ‘1 kilo of ingredients, 6 tbsp of base’. The following will assume that you’re working towards 1 kilo in your pot — scale up or down accordingly.

In a small saucepan over a low flame, melt together

2 tbsp Sichuan hotpot base

4 tbsp Laoyou

½ tbsp oyster sauce

½ tbsp sweet bean paste (甜面酱)

1 tsp sugar

1 tsp 13 spice powder (十三香) -or- 5 spice powder

½ tsp MSG

This will be your base for the dry pot. Then, when frying, begin your stir fry with:

2 tbsp oil

4 cloves garlic, smashed

~1 inch ginger, smashed

1 tsp Sichuan peppercorns

~4 spicy dried chilis, cut into sections

Before adding the base. Once mixed, fry your pre-prepped ingredients with the base before seasoning to taste with salt and MSG (~¼ tsp each). You can also add in onion, cilantro, Chinese celery, and/or toasted sesame seeds. Transfer to a sizzling dry pot and serve.

Minced Celery with Beef (芹菜碎牛肉, aka “THE DISH”)

This is a much beloved dish on our Discord — so much so that for a hot second people simply referred to it as ‘The Dish’. It was introduced to them via the renowned Fuchsia Dunlop, and our competitive streak led us to want to cover the dish in our previous Over Rice: Sichuan Edition video.

This recipe is an adaptation of said recipe, swapping out the Chili Bean Paste for Laoyou. Many Sichuan dishes could be given a similar treatment.

Hand mince

150g beef loin

To do so, first slice into a rough dice, then mince for ~5 minutes. Mix with a marinade of:

¼ tsp dark soy sauce

1 tsp Shaoxing wine

⅛ tsp salt

¼ tsp cornstarch

and set aside.

You may use either

220g western celery -or- Chinese celery

for this dish. If using the latter, simply cut into a ~½ cm dice and reserve.

If using western celery, first peel off the fibrous outer layer. Separate the leaves from the remainder of the celery. Cut the celery into a ~½ cm dice, and roughly chop the leaves. Set the leaves aside.

Mix the diced celery with the ¼ tsp salt, and purge for 10 minutes. After that time, squeeze the celery to expel as much water as possible. Reserve.

Mince the aromatics:

½ inch ginger

3 cloves garlic

and reserve.

In a wok over a medium high flame, add in ~2 tbsp of oil and give it a swirl. Add in beef, quickly break it up. Fry it until the color's changed and the beef is cooked.

Turn off the flame and scooch the beef to the side. Add in the aromatics, and fry over a medium-low flame for ~1 minute until fragrant. Then add in

1 tbsp Laoyou, with sediment

mix the beef back in and turn the heat to high. Stir fry for ~15 seconds, add in the celery and briefly stir fry again. Then swap the flame to medium-low, and add in a sauce of:

1.5 tbsp stock

½ tbsp soy sauce

¼ tsp MSG

⅛ tsp salt

and mix well. Drizzle in a slurry of

½ tsp cornstarch

1 tsp water

in a thin stream until thickened. Drizzle in

1 tbsp Laoyou, without sediment

and mix. Heat off, and if using western celery, add the chopped celery leaves at this point. Mix, and serve.

Yanjian Pork (盐煎肉)

This dish is quite similar to Twice Cooked Pork, only… without having to cook twice. Personally, I prefer pork shoulder over pork belly for this texturally, as sans-boiling the fat will be a bit less ‘snappy’ than Twice Cooked Pork.

Slice

300g pork shoulder -or- pork belly (without skin)

into 2mm slices, roughly a square inch in size. We will not need to marinate.

Cut

3 stalks (~75g) green garlic (蒜苗) -or- scallion (小葱)

Separate the white from the green. If using green garlic, cut the greens into the “horse ear” (马耳朵) shape. To do so, hold your knife at about a 30 degree angle, while also slicing the greens at a bias, into ~½ inch sections.

To stir fry, first swirl in

1 tbsp oil

and fry the pork slices on medium. Once the pork is loosened and the exterior is no longer obviously ‘raw’, sprinkle in

⅛ tsp salt

and stir fry until the oil becomes clear again, and the pork curls slightly. Scooch the pork up the side of the wok, then add in

2 tbsp laoyou, sediment included

1 tsp Sichuan sweet bean paste (四川甜面酱), preferably -or- northern Chinese sweet bean paste (甜面酱) -or- Cantonese Ground Bean Sauce (磨豉酱)

and the white sections of the green garlic/scallion. Fry over a medium flame until fragrant and the whites slightly softened, ~30 seconds. Scooch the pork back to the center and up the flame to high.

Briefly stir fry together, then swirl in

1 tsp soy sauce,

mix, and sprinkle in ⅛ tsp MSG and the green part of the green garlic. Briefly stir fry together for ~15 seconds.

Hula “Scorched Chili” Oil

Slice

60g fragrant chili pepper (e.g. Erjingtiao, Zidantou, Guajillo, Aleppo)

into roughly 1 inch sections, tossing the stem. Reserve.

In a small bowl, combine

10g Red Sichuan Peppercorns (花椒)

with about a half shot of baijiu liquor (or vodka) and reserve.

In a wok, add

2 cups oil (e.g. Caiziyou, Mustard Seed, Peanut, or Olive)

½ onion, finely sliced

~5 scallions, chopped

~2 inches ginger, smashed

and fry over a medium flame. After about ten minutes, wet the following spices with a bit of strong liquor, e.g. baijiu or vodka. Any spices that you cannot find may be omitted:

3 dried bay leaves (香叶)

3 slices or ~2g sand ginger (沙姜)

1 Tsaoko (草果), Chinese black cardamom, peel only

1 tbsp Sichuan Peppercorn (花椒)

2 star anise (八角)

~⅓ Cinnamon stick (桂皮)

½ tsp Fennel Seed (小茴香)

Add the spices into the bubbling oil, and continue to cook until the onions are golden brown, 8-10 minutes more. Strain, returning the oil to the wok.

Heat the oil up to roughly 130C and add in the sliced chilis. Fry for 6-7 minutes, or until the chili reaches a deep chestnut color. Strain, remove, and place in a bowl.

Add in the Sichuan peppercorns and deep fry for ~2 minutes, or until the peppercorns have expelled their moisture. Shut off the heat, and use a strainer to transfer the peppercorns over to the chilis.

With a ladle very roughly crush some of the chilis in the bowl. This is optional, and you certainly do not need to be obsessive. We are simply trying to allow our chilis to be able to pack a little more efficiently.

Transfer the oil into the bowl with the chilis. Once completely cool, it can be stored in a jar. You will likely not be able to fit all of the chilis in the jar — that’s okay, simply store the rest as hulake sans oil.

Recipes Using Hula ‘Scorched’ Chili Oil

Kung Pao Shrimp (宫保虾球)

Kung Pao Chicken is obviously the most common ‘Kung Pao’, but we’ve covered it multiple times before. Shrimp is likely the second most common implementation.

For ours, we employed some Cantonese techniques when it came to the shrimp preparation — we covered the logic of these techniques in our previous Shrimp: The Maximally Delicious Way video. If you have a different way to prep shrimp for stir fry that you prefer, use that!

This was one of my favorite dishes that we’ve made using this batch of chilis oils. Unfortunately, I apparently neglected to take a picture the first two times I made it, and we ran out of cashews for the test in the below picture. In the recipe we call for cashews, but you can also obviously use peanuts as well, like below:

Peel

550g shell-on, head on shrimp

You should be looking at 275-300g after peeling.

Rinse, then submerge the shrimp with water in a bowl and mix in

1/2 tsp sodium carbonate

Let sit for ten minutes. Rinse again, then let the shrimp sit under running water for ~3 minutes.

Drain, then transfer to a paper towel. Lightly squeeze out any excess liquid. Move over to a rag or kitchen towel and roll it up to finish drying.

Butterfly the shrimp, and remove the vein. Pat again with a paper towel, then transfer to a bowl. Marinate with:

⅛ tsp salt

¼ tsp sugar

¼ tsp white pepper

½ tsp Shaoxing wine

½ tsp cornstarch

½ tbsp Hula chili oil, oil only (optional)

We will pass the shrimp through oil. To do so, in a wok, heat roughly 1 cup of oil up to about 160 celsius. Add in the shrimp, and cook until they visually look ‘done’, ~30 seconds. Remove, strain, and dip the oil out of the pot.

Separate the white part green part from

1 stalk green garlic (蒜苗) -or- 2 scallions

cutting the white part into sections and slicing the green part9.

Slice:

2 cloves garlic

1 cm ginger

and reserve.

In a wok over a medium flame, swirl in

1.5 tbsp oil (this can be repurposed from the shrimp frying oil)

and fry the garlic, ginger, and white part of the green garlic (or scallion) until fragrant, ~30 seconds. Add

Hula chilis, together with the oil. Aim for about ~14 chili sections with a few Sichuan peppercorns in the mix. Include a bit of oil, ~½ tbsp to ~1 tbsp

Mix, then up the flame to high. Swirl in

1 tbsp Shaoxing wine

then add in the shrimp, together with

60g fried, toasted, or roasted cashew10

and stir fry for 15-30 seconds. Add a sauce of:

3 tbsp stock

2 tsp sugar

1.25 tsp soy sauce

¾ tsp dark Chinese vinegar, preferably Baoning (保宁醋) or Zhenjiang/Chinkiang vinegar (香醋)

¼ tsp salt

¼ tsp chicken powder

⅛ tsp MSG

⅛ tsp white pepper

Let rapidly boil for ~15 seconds, then swap the flame to low. Drizzle in a slurry of

½ tsp cornstarch

½ tbsp water

and taste once thickened. Add in the green part of the green garlic or scallion, mix, and finish with

1 tbsp Hula chili oil, oil only

Pickled Chili Oil

Note: This recipe will require large, mild pickled chilis — in Sichuan, pickled Erjingtiao chilis are used (泡二荆条), but similar products exist around southwest China. These are fermented, and very, very sour. While the pickled Heaven Facing chilis used in this recipe seem to be available outside of China, the mild pickled chilis unfortunately appear very difficult to find in most places.

You could, perhaps play around with Korean pickled chilis, but to my understanding these are only available green (so color would obviously be very different). If going this route, you could perhaps add in ~2 tbsp of Pixian Doubanjiang to compensate for the color. Alternatively, given the intense sourness, western-style vinegar pickled chilis may also make sense if they weren’t pickled with not too many western herbs and spices. I’ve never tried either route myself however, so either substitute would be quite experimental.

Slice

280g large, mild pickled chilis (泡二荆条)

80g spicy pickled chilis (泡朝天椒)

into rough sections, tossing the stem.

Transfer the large, mild chilis to a strainer, and squeeze out the excess moisture. You should be looking at ~140g of mild pickled chilis after straining (you do not need to strain the spicy pickled chilis).

Combine together with

60g pickled ginger (泡姜)

and pickle together into a fine paste. This will take about 10-15 minutes to get thoroughly pasty — you can also use a food processor. Reserve.

In a wok, add

1.5 cups oil (e.g. Caiziyou, Mustard Seed, Peanut, or Olive)

¼ onion, finely sliced

~5 scallions, chopped

~2 inches ginger, smashed

and fry over a medium flame. After about ten minutes, wet the following spices with a bit of strong liquor, e.g. baijiu or vodka. Any spices that you cannot find may be omitted:

3 dried bay leaves (香叶)

3 slices or ~2g sand ginger (沙姜)

1 tbsp Green Sichuan Peppercorn (青花椒) -or- Red Sichuan Peppercorn

Add the spices into the bubbling oil, and continue to cook until the onions are golden brown, 8-10 minutes more. Strain, returning the oil to the wok.

Add the pickled chili mixture to the oil. Swap the flame to medium/medium-high flame, and fry the mixture until the chilis lose a bit of their obvious redness, looking closer to a ‘cooked chili’ than a ‘fresh chili’, 8-10 minutes. Shut off the heat and let cool down.

Store in an airtight jar, preferably in the fridge.

Recipes Using Pickled Chili Oil

Pickled Chili Rice Noodle Soup

At its core, this soup is a very similar idea as the Mala Hotpot Noodles above — make a base, add in your add-ins. The primary difference is the flavor profile of said base, though this dish is (obviously) also much more likely to reach for the titular rice noodles.

Soak, or cook, according to the package:

100g dry rice noodle (米线/米粉)

10g kelp/konbu (干海带/昆布)

For our dried rice noodles, we soaked with hot water until no hard bits remained at the center.

Roughly crush, then and chop:

4 pickled chilis

1 small tomato

1 inch pickled ginger, optional

all into 1-2cm chunks.

Mince

1 clove garlic

½ inch ginger

and set aside.

Cut

60g napa cabbage (娃娃菜/黄芽白)

40g enoki or oyster mushroom (金针菇/秀珍菇)

1 stalk (20g) cilantro

and the reconstituted kelp from above into 1-2 inch long sections and set aside.

Prepare

150g of meat/meat products — your choice of frozen meat/fish balls, crab stick, fish tofu, spam, hot dog, or thinly sliced hot pot beef/pork (肉丸/午餐肉/火腿肠/火锅牛肉/火锅猪肉)

To a pot, heat on medium low, add in

2.5 tbsp pickled chili oil, with sediment

½ tbsp lard or schmaltz (optional)

together with the minced garlic and ginger and fry until fragrant, ~45 seconds. Then add in

1 cup stock

1.5 cups water

¼ tsp MSG (味精)

½ tsp sugar

½ tsp soy sauce

1 tsp Dark Chinese Vinegar (陈醋/镇江香醋/保宁醋)

Add in the kelp and mushroom, bring to a boil and simmer for 3 minutes.

Add in napa cabbage and your choice of meatballs/spam/or hotdog. Cook for 2 minutes or until the meatballs/spam floats.

Add in the softened/cooked rice noodles, and cook for about 30 seconds to absorb the flavor. If using thinly sliced hot pot meat, add in together with the rice noodles. When the noodle is done, shut off the heat.

Season to taste. Pickled chili can sometimes be salty, which is why we did not include salt. You may need to add in an additional ⅛ tsp.

Finish with

1 tsp pickled chili oil, without sediment

⅛ tsp white pepper powder

‘Broken Rice’ Chicken (碎米鸡丁)

This is an old school Sichuan dish adapted from 大众川菜. There is no ‘broken rice’ in the dish, the name refers to the shape of the chicken.

Slice

250g chicken thigh

into a fine dice ~1/2 cm dice, then marinate with

¼ tsp salt

¼ tsp chicken powder

½ tsp Shaoxing Wine

⅛ tsp white pepper

1 egg white

1 tbsp cornstarch

1 tbsp oil to coat

We will then pass the chicken through oil. To do so, add roughly one cup of oil to a wok and heat it up over a high flame. Once the oil has reached ~170C, add the chicken and fry until cooked, ~45 seconds. Remove, drain, and set aside.

Roughly crush

50g toasted, roasted, or fried peanuts

and set aside.

Separate the whites from the greens from

3 scallions,

slice green and set aside. Finely mince the white part together with

3 cloves garlic

1 cm ginger

~8 pickled heaven facing chili

and also set that aside.

To stir fry, in a wok swirl in

1.5 tbsp lard

and over a medium low flame fry the minced scallion whites/garlic/ginger/and pickled heaven facing until fragrant, ~45 seconds. Then add in

1 tbsp pickled chili oil, with sediment

and up the flame to high. After a brief mix, swirl in

1 tbsp Shaoxing wine

and add in the peanuts. Brief mix, then add in the chicken. Stir fry for ~30 seconds, then add in a sauce of

2 tsp vinegar

2 tsp soy sauce

1 tbsp sugar

¼ tsp chicken powder

⅛ tsp salt

⅛ tsp MSG

and swap the flame to medium low. Drizzle in a slurry of

½ tsp cornstarch

½ tbsp water

and once thickened, season to taste. We added an additional

⅛ tsp salt

⅛ tsp sugar

¼ tsp MSG

Mix in the sliced scallion greens, then drizzle in an additional

1.5 tbsp pickled chili oil, without sediment

and serve.

Chengdu-style Tomato and Egg Noodle Soup

This recipe does not actually contain pickled chili oil, instead serving it on the side. This was an idea that we picked up from a restaurant in Chengdu called ‘Kangji Tomato and Egg Noodles’ (康记煎蛋面) — at the shop, they even have extra pickled chili oil available for purchase. It goes very well with this soup.

Note that the recipe below does not use the traditional method for egg frying that you’ll see with this dish in Chengdu (which is sort of halfway to a deep-fry). Instead, we opted for a general sort of pan-fried egg, like you might see with hebaodan (煎荷包蛋). Sometime soon we’ll cover this recipe with a proper video.

First, peel

600g (or about 3 medium) tomatoes

by slicing in a small ‘x’ on the bottom, and boiling in water for 1-2 minutes. Rinse under cool water, and remove the peel. Roughly mince the tomato, being sure to keep all of the juice of the tomato. Transfer to a large bowl, and mix well with

¼ tsp salt

1 tbsp Shaoxing wine

and let sit as you prep everything else.

Separate the whites from the greens from

2 scallions,

slice green and set aside. Finely mince the white part together with

3 cloves garlic

1 inch ginger

and set aside.

Slice

150g pork belly

into ~½ cm strips, mix with

½ tbsp oil

and add to a cool, dry wok (or pot). Up the flame to medium. Spread out the pork slices and render out the lard. Flip periodically. You do not need to nurse it, but to make sure to give it a stir every once in a while to make sure that things aren’t scorching or cooking unevenly. Once brown and crispy, strain into a bowl. Reserve the rendered lard, and the crispy pork in a separate bowl.

In a pot, wok, or (preferably) claypot, add in

3.5 tbsp of the rendered lard above

and over a low flame fry the aromatics until fragrant and softened, ~2 minutes. Then add in

½ tbsp tomato paste

and fry until the lard is stained, ~1 minute more.

Add in the tomatoes, and swap the flame to medium. Once everything is rapidly bubbling, add in

¾ cup stock

¾ cup water

½ tbsp sugar

½ tbsp chicken bouillon powder

½ tsp salt

½ tsp MSG

¼ tsp white pepper powder

Simmer the mixture for at least 15 minutes. You can fry the eggs and cook the noodles as you are simmering.

To fry the eggs, we will use

4 eggs

for two people. Crack two eggs into a bowl and sprinkle a touch of salt on. Do not whisk. In a separate bowl, do the same with the other two eggs.

To a hot wok, swirl in

2-3 tbsp lard, from above

and with the heat on high, add in one of the bowls of eggs. Roughly break the yolk with the spatula and give it a stir. Let the egg puff and wait for the edge to set. Flip, fry the other side for 30-45 seconds. Flip it back, let it fry for another 30 seconds. Remove and set aside. Add another 2 tbsp lard to the wok and repeat with the other two eggs.

Add water to the wok, then boil

200g dried noodles

until done. Split between two serving bowls.

Serve the noodles alongside the fried eggs, the tomato soup, the scallion greens, the crispy pork, and the pickled chili oil. I like ~1 tsp of pickled chili oil in my soup, Steph likes ~1 tbsp in hers.

Fresh Chili Oil

Mince

140g spicy fresh chilis (e.g. Heaven Facing, Thai Bird’s eye)

60g ginger

together, and set aside.

Separately mince

80g young ginger11

and set that aside as well.

In a wok, add

1.5 cups oil (e.g. Caiziyou, Mustard Seed, Peanut, or Olive)

¼ onion, finely sliced

~5 scallions, chopped

~2 inches ginger, smashed

and fry over a medium flame. After about ten minutes, wet the following spices with a bit of strong liquor, e.g. baijiu or vodka. Any spices that you cannot find may be omitted:

3 dried bay leaves (香叶)

3 slices or ~2g sand ginger (沙姜)

1 tbsp Green Sichuan Peppercorn (青花椒) -or- Red Sichuan Peppercorn

Add the spices into the bubbling oil, and continue to cook until the onions are golden brown, 8-10 minutes more. Strain, returning the oil to the wok.

Add the minced young ginger to the oil, then swap the flame to medium-high flame. Once the young ginger has lost a bit of its angry moisture, add the chili/ginger mixture. Fry it all until the chilis lose a bit of their obvious redness, looking closer to a ‘cooked chili’ than a ‘fresh chili’, 8-10 minutes. Shut off the heat and let cool down.

Transfer to storage. The oil will keep in the fridge for 1-2 weeks.

Recipes Using Fresh Chili Oil

The most famous dish using this is Zigong’s Fresh Chili Rabbit. You can see the always fantastic Wang Gang make the dish here:

Fresh Chili Beef Noodle Topping (鲜椒牛肉面)

Note that this dish is very spicy, so do feel free to cut back the fresh chili in accordance with your own tolerance level.

First, place the base seasoning in your noodle serving bowl:

⅛ tsp salt

⅛ tsp MSG (味精)

2 tsp soy sauce (生抽/酱油)

½ tsp dark Chinese vinegar (陈醋/镇江香醋/保宁醋)

1 tbsp Mala chili oil (optional, for extra spicy)

and set aside.

Marinate:

200g ground beef, preferably coarsely ground

¼ tsp salt

and set aside.

Mince

3 big cloves of garlic

1.5 inch (25g) ginger

30g spicy fresh chili like Heaven Facing Chili or Thai bird’s eye. For a nicer color you can use a mix of red and green.

10g scallion

10g cilantro

In a hot wok, swirl

2-3 tbsp oil

and fry the beef until separated and cooked. Remove the beef and reserve. Toss any remaining oil, then over a medium flame add in

1.5 tbsp Fresh Chili Oil

and the ginger and garlic. Briefly fry, then add in about half the fresh chili. Fry for ~30 seconds, then up the flame to high. Add back in the beef and briefly stir fry. Swirl

½ tbsp Shaoxing wine

around the sides of the wok, then add in the remaining chilis.

Swirl in

1 tbsp soy sauce

around the sides of the wok, and then season to taste. We added

⅛ tsp salt

¼ tsp MSG (味精)

Mix well, then heat off. Finish with

½ tbsp fresh chili oil

While you’re stir frying the beef, on another burner, boil

100g dry noodle (鸡蛋面/枧水面)

According to package until it’s done. Strain but do not shock the noodles with cold water. Add to the noodle serving bowl with seasoning inside. Top the noodles with the stir fried beef, the scallion and cilantro, and mix well.

If you do not find it salty enough, add a little more salt and soy sauce to taste.

Fresh Chili Rice Noodle Sauce

Because the fresh chili does not keep, this can be a good way to use up the oil before it goes.

To a bowl, mix

1 tbsp fresh chili oil, sediment included

½ tbsp soy sauce (生抽)

¼ tsp salt

¼ tsp sugar

⅛ tsp MSG (味精)

2 tsp oyster sauce (蚝油)

This will be enough to season 250g worth of fresh rice noodles, or 150g of dried. A little chopped cilantro and scallion can also be nice.

A dish like Yi people’s pounded chicken might be a nice application, but you could also simply shred it and dress it with the ‘Cold Salad Formula’ in this post.

Any Thai speakers, help me out. At our local market in Huai Khwang, the vendors would literally refer to the thing as “พริกใหญ่”. It seems to be available for purchase on Lazada under that name too, but I can’t seem to figure out if there’s a more ‘proper’ name for the cultivar than ‘big red chili’?

Refined, bleached, and deodorized. The most common rapeseed oil in the West — Canola — is processed into a neutral oil. Caiziyou is very different.

Sometimes the rapidity of the blades of a food processor can continue to cook the chilis past done.

If you cannot find sand ginger, dried galangal is a nice substitute. If you cannot find either, skip it.

To peel a Tsaoko, slice the two ends and pry it open with a knife. The process will feel awkward. If you find it difficult to peel, you can use the whole Tsaoko without peeling.

The crispy fried aromatics are not used in the recipe, but are delicious to munch on — and make for a fantastic burger topping.

This is a trick that I picked up from making curry pastes in Thailand. The salt will help the ingredient break down, and the garlic will help to emulsify. Note that while in neighboring Guizhou aromatics aren’t unheard of in a ciba chili paste, to our understanding this would be un-standard practice in Sichuan.

For green garlic, we sliced it into the classic ‘horse ear’ shape. To do so, hold your knife at about a 30 degree angle, while also slicing the greens at a bias, into ~½ inch sections.

If you have raw cashew, you can fry the cashews in that cup of shrimp ‘passing through oil’ oil, before the shrimp. Will also add some slight nuttiness to the oil.

If young ginger in unavailable to you, up the ginger quantity to 100g. You could also play around with young galangal if you wanted to be experimental.

Caiziyou, or, rapeseed oil, can be easily found online. (yamibuy.com for one)

Happy cooking!

Wow, encyclopaedic! Haven't finished reading it yet, but just wanted to say thanks for all the time and effort you poured into this 💐.