Are "Thai Salads" (Hakka) Chinese?

The yam-yan connections that drove me to the edge of my sanity.

There’s no dish that tickles my brain as ‘Thai’ quite more than a Yam salad.

It’s not just their sheer ubiquity in Bangkok, though if I’m honest that’s probably part of it too. If you were to draw one of those little “15 minute city” maps for any given Bangkok neighborhood, I’d bet solid money that you could find a back-alley vendor slinging up a yam within. In a restaurant setting, Yam’s not only a menu fixture, there’s entire restaurants that specialize in the stuff. Our neighborhood’s got a popular chain right outside the metro, and practically every weekend sports an impressive lineup of people waiting to pre-game with their mélange of yam offerings.

I’m not a believer in waiting in restaurant lines, so our favorite yam joint’s down the road, set-up in the shaded corner of an old 70s era housing project. It’s impressively cheap, and a great accompaniment to an ice cold Singha on a muggy night:

Of course, when it comes to these sorts of cultural touchstones, you could be similarly sentimental with Som Tam or even Mu Krata. So to me, it’s the flavor of the thing that hits me as ‘Thai’ above all else. It’s like you took all the stereotypical Thai ingredients - chilis, garlic, lime, fish sauce, a glorious fuck ton of sugar - and smashed them all into one singular dish.

When we move back to China, if I ever want to cook something that harkens back to our time in Bangkok… a Yam would be the top of the list. To me, the stuff just tastes like Thailand.

Where are ‘Thai Salads’ from?

While I’m guilty of perhaps teasing otherwise in the title, let me make it abundantly clear here: “Thai salads” are from… Thailand. Like, by definition. This is not one of those weird Cantonese ‘Singapore Fried Rice Noodles’ situations. These are Thai dishes.

But we’re all food geeks here, right? As a community, we’re pretty enamored with food origin stories. Did you know Ketchup was Chinese originally? Did you know Tikka Masala was invented in England? Did you know chilis are from the Americas?…

We’re, admittedly, pretty fun at parties.

So in the interest of self-indulgence, let’s take a look at the stuff that’s usually translated into English as “Thai Salads”. While there’s a few others (Phla, Goi, Sa, Miang), generally speaking there’s three major categories you see on menus in the west as ‘salad’:

First, there’s stuff that’s referred to as Dam. Internationally, the most famous Dam is “Som Tam” (Tam is an alternative romanization for Dam), or Papaya salad, which tracks with the domestic situation in Thailand as well. But there’s other Dams too - one of my favorites is the Young Jackfruit Dam from up in Lanna. Linguistically, this is an old word that’s common in the Tai speaking world that means ‘hit’ or ‘pound’, and so - predictably - lightly pounds ingredients in with a sauce in a large mortar to make the salad.

Cool. Moving on, there’s also Laab. Now, I’m going to be upfront here - I really, really hate the ‘Salad’ translation for Laab. For the unaware, Laab are minced meat dishes - sometimes cooked, sometimes raw - that are served with sticky rice and fresh vegetables on the side. I suppose they’re also ‘mixed’ so maybe the salad translation works if you squint, but at that point we might as well refer to Spaghetti Bolognese as “Italian Noodle Salad”. In any event, Laab is also a word that’s common in the Tai speaking world, and the dish is especially prevalent in Northern Thailand, Isaan, and Laos.

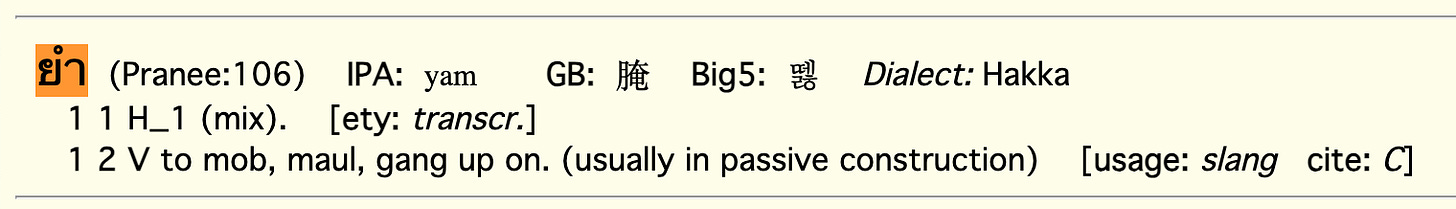

Great. Now let’s get to the aforementioned Yum. Fire up the ol’ Wiktionary, and…

Etymology uncertain. Compare Khmer ញាំ (ñŏəm, “Cambodian salad; to make a Cambodian salad”); Hakka 醃/腌 (âm, “to marinate; to pickle”).

Hakka Chinese? That’s… odd. Curiosity officially piqued.

Because if you sounded out that character - 腌 - in the Meizhou dialect of Hakka, it’s pronounced practically the same (sometimes romanized as ‘Yam’) - the only thing that’s different there is the tone.

Okay, so let’s swap that Wiktionary link into Thai so we can do source diving. Sure enough, here we’ve got a list of modern loanwords into Thai from Chinese via Chulalongkorn University, and…

…now you’ve got my attention.

Hakka? WTF is going on here?

We’ve now officially left the airspace of ‘culinary arts’ and entered ‘historical linguistics’, which is a much bumpier realm indeed. And, let’s make this abundantly clear: we are definitely not historical linguists.

So instead, let’s try to ground this in food. We’ve already talked a bit about Yam in Thailand, so what does âm/yam (hereafter ‘Yam’) mean in the Hakka world?

Well - just like the Thai word - this character refers to dishes that are mixed. By far the most famous Hakka Yam dish is Yam Mian, which mixes noodles with garlic, lard, and fish sauce:

But that’s not the only Yam dish out there. The ever-excellent A Xing has a (subbed in English!) video of a Hakka Yam feast in Fengshun, so you can get a sense of the diversity. For us, one of our all time favorites is Yam Beef (腌牛肉), an addictively simple dish of boiled beef slices mixed with chilis, soy sauce, and garlic:

So… I think we can do this - let’s teach you how to make Hakka Yam Beef, then try juxtapose it against a Thai Yam (a beef Yam, perhaps, for an apples-to-apples comparison). After looking at the modern Yam incarnations in their respective cultures, maybe we’ll be able to better piece together what’s going on.

Or maybe not. Worst comes to worst, you’ll just have learned two delicious - and pretty easy - dishes.

Hakka Yam Beef (腌牛肉)

To reiterate, Hakka Yams have a… metric ton of variation. Most obviously, you can find the dish with or without chili pepper (e.g. the restaurant A Xing went to above did not use chili). The one mandatory constant is garlic, but the form of said garlic can also vary - some people use fresh garlic, other garlic oil, and some a combination.

Our goal here was to aim for the above Yam Beef that we ate in Meizhou. They - interestingly - use a combination of raw garlic and garlic oil. They also included chili oil, as well as a touch of minced tomato (a rather uncommon addition).

Ingredients:

Garlic (大蒜), 5 cloves. Finely minced. Two thirds will be used fresh in the sauce and one third will be fried to make the garlic oil.

Peanut oil (花生油), 1½ tbsp. For the garlic oil.

Douchi (豆豉), 6 (optional). For the garlic oil.

Chinese celery (芹菜), 1 stalk. Minced.

Tomato, ⅛ medium. Roughly minced.

Cucumber, 50g. Peeled, smashed, and cut into chunks.

Red mild chili, ½. Sliced.

Cilantro, 30g. Or about two stalks, chopped into roughly one inch sections.

Beef loin (牛里脊), 200g

Marinade for beef:

Salt, ⅛ tsp

Sugar, ⅛ tsp

Soy sauce (生抽), ¼ tsp

Cornstarch (生粉), 1 tbsp

Water, 1 tbsp

For the sauce:

MSG (味精), ¼ tsp

White pepper powder (白胡椒粉), ¼ tsp

Sugar, ½ tsp

Soy sauce (生抽), 1½ tbsp

Chili oil (辣椒油), 1 tbsp. We used a Hong Kong chili oil, but a Shanghai (or Japanese) style chili oil would be milder and more appropriate for the dish. A Sichuan style chili oil would be… different… but not necessarily undelicious in our opinion.

Fresh garlic and garlic oil from above

Process:

To make the garlic oil:

Finely, finely mince five cloves of garlic. Reserve ⅔ of it to a separate bowl. Add the remaining ⅓ to a cool pot with 1.5 tbsp of peanut oil. Swap the flame to medium-low, fry for 4-5 minutes, or until the garlic is golden brown. Add an optional six douchi to the oil and shut off the heat. Once the douchi have stopped bubbling, reserve the fried garlic/douchi together with the oil.

To prep:

Mince one stalk of Chinese celery and roughly ⅛ of a medium tomato. Peel 50g of cucumber, smash flat, and cut into half inch chunks. Slice half a red mild chili. Chop 30g (two big stalks) of cilantro into roughly one inch sections.

To marinate and blanch the beef:

Slice 200g of loin into 2-3mm slices - ideally, roughly two inch wide and one inch high. Marinate with ⅛ tsp salt, ⅛ tsp sugar, ¼ tsp soy sauce, and one tablespoon each cornstarch and water. Mix well til combined and slightly sticky.

To blanch get a wok or pot of water up to a boil. Swap the flame to low, adding the beef bit by bit so that it doesn’t clump into a big mess. After all the beef’s in, swap the heat to high. Once the beef’s changed color, shut off the heat, remove, and strain.

To assemble:

To a mixing bowl, add in ¼ tsp MSG, ¼ tsp white pepper, ½ tsp sugar, tablespoon half soy sauce, one tablespoon of chili oil, and the garlic oil we just made.

Quick mix, then go in with the rest of the fresh minced garlic, the minced Chinese celery and tomato, the cucumber, and the chili. Mix, then add the blanched beef and cilantro and mix well again.

Thai Yam Beef (ยําเนื้อย่าง)

The Yam sauce that we used in this recipe is adapted from the excellent Boontiwa Indoor. She is a Thai Food YouTuber that shares some fantastic recipes, though unfortunately not in English. In particular, she has these really pretty awesome instructional videos aimed for prospective street food vendors in Thailand, where she not only shares a recipe… but also discusses logistics and (sometimes) even gives a profitability breakdown.

If you’re in the market to supplement your go-to Hot Thai Kitchen recipes with some local Thai sources, you could definitely do a lot worse than Boontiwa Indoor.

Ingredients:

For the yam sauce:

Spicy chilis (e.g. Heaven Facing, Thai Bird's eye), 15g

Garlic, 15g

Cilantro roots, 2

Fish sauce, 15g

Hot water, 7.5g

Golden syrup, 30g. This is a substitute for simmered sugar (น้ำตาลเคี่ยว), an ingredient often seen in Thai street food. Gin Dai Aroy Duay has a recipe if you’re curious. You can also use honey to substitute, which I’ve seen from Hot Thai Kitchen - cheap honey is basically golden syrup by any other name.

Lime juice, 30g. Freshly squeezed from ~2-3 limes.

Sugar, ¾ tsp

MSG, ¾ tsp

For the Grilled Steak Yam:

Steak, ~250g. Dealer’s choice.

Marinade for steak:

Salt, ¹⁄₁₆ tsp

Sugar, ¼ tsp

Chicken bouillon powder, ¼ tsp. We used Rot Dee, Thai-style chicken bouillon powder. It is similar to Chinese chicken bouillon powder, but also contains small quantities of garlic and onion powder, white pepper powder, and coriander seed powder.

Fish sauce, ⅛ tsp

Soy sauce, ⅛ tsp. Or, alternatively, Maggi sauce.

Oyster sauce, 1 tsp

Red onion, ½ small. Sliced.

Tomato, ¼ medium. Sliced.

Chinese celery, 4 sticks. Chopped into one inch sections.

Cucumber, 100g. Chopped into two inch chunks.

Additional seasoning (to taste):

Lime juice. We added a squeeze.

MSG, ⅛ tsp

Sugar, ⅛ tsp

Fish sauce, ¼ tsp

Process:

To make the Yam sauce:

Pound - or finely, finely mince - 15g of spicy chilis (e.g. Heaven Facing, Thai Bird’s eye) and 15g of garlic. Finely mince the roots of two cilantros. If you do not have access to cilantro root, mince the stem together with a touch - ½ cm, or even less - of ginger.

Mix the above with 15g fish sauce, 7.5g hot, boiled water from the kettle, 30g of golden syrup, and 30g of freshly squeezed lime juice. Add ¾ of a tsp each of granulated sugar and MSG, or to taste. There should be an intensity to the sauce. It should feel borderline… too spicy, too sour, too sweet - mellowed out a bit by the fish sauce and MSG.

Feel free to scale up the sauce and keep the stuff for various yams. I don’t know how long it keeps because it seems to get consumed faster than I can find out.

To grill the steak:

Pound a (roughly) 250g steak into a thickness of about a half an inch. Marinate with 1/16 tsp salt, ¼ tsp sugar, ¼ chicken bouillon powder, ⅛ tsp fish sauce, ⅛ tsp soy sauce, and 1 tsp of oyster sauce.

Marinate for at least a half an hour. Grill until a ‘not paranoid’ well-done, then let it rest for at least ten minutes. Slice into roughly ½ cm strips.

To prep and assemble:

Slice a half a small red onion and a quarter of a medium tomato. Chop four sticks of Chinese celery into about one inch chunks. Peel and chop 100g of cucumber into roughly two inch chunks.

Mix these ingredients with the sliced steak and the yam sauce from above. Taste, and adjust to your liking. We added another squeeze of lime, ⅛ tsp each MSG and sugar, and ¼ tsp of fish sauce.

Analysis

So at a fundamental level, our Hakka Yam Beef is a mixed dish of boiled beef, Chinese celery, and cucumber. The sauce is heavy on the garlic, and some soy sauce is pretty much mandatory. Our version included chili oil, which is quite common but definitely not required.

The Thai Yam Beef, meanwhile, is a mixed dish of grilled beef, but many other Yum dishes use boiled ingredients. It’s then mixed with onion, tomato, and Chinese celery. The sauce is an intense affair of chili, garlic, lime, fish sauce and sugar. An odd commonality here is the cucumber - Yam dishes in general don’t necessarily need it, but it’s a very common addition to specifically the grilled beef yam.

There’s enough differences that I think we can definitely say that they’re not the same ‘thing’. But… there’s also enough similarities - culinarily and linguistically - that there might actually be something to this? It’s certainly a lot closer than a bottle of Heinz is to 16th century Hokkien fish sauce.

After thinking on the problem for a bit, we have our own hypothesis (emphasis on hypothesis):

The Thai word, ‘Yฟm’, and its corresponding dish, is not from Hakka.

We think it’s from Chaozhou.

Our Chaozhou Hypothesis

Now we talked about the Chaozhou-Bangkok connection in an earlier video. If you’re interested in the topic, I’d recommend watching the whole thing.

The TL;DR is that a lot of Thailand has Teochew ancestry (Teochew is an alternative romanization of ‘Chaozhou’, one that’s usually used in Southeast Asia). The very founder of the Kingdom of Siam was Teochew, and Teochew immigrants formed the backbone of the country’s urban class and petit bourgeoisie. In the the first half of the 20th century, the Thai state embarked on a program of forced assimilation known as ‘Thai-ification’, focused on bringing in the Thai-Chinese and Lao in Isaan under the “Thai” ethnic banner.

However you feel about the topic of forced assimilation, Thai-ification was unquestionably successful in its aims. By the mid 20th century, a clear Thai identity was formed, and the previous ethnic divisions manifested themselves mostly as class divisions, if at all.

So when it comes to food, there ends up being these really fascinating Teochew-Bangkok connections simmering under the surface. Some of them are obvious, others not so much:

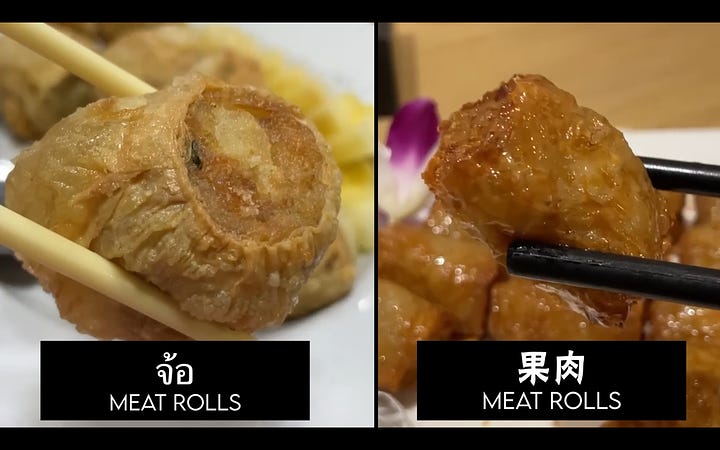

One of the clearer similarities, however is this dish - Chaozhou sashimi, “Sheng Iam”. ‘Iam’, of course, being pronounced ‘Yam’:

Now, raw fish is popular in many places in south China, but the specific variant they have in Chaozhou has an intense marinade with… soy sauce, chili, garlic, vinegar, and herbs.

Meanwhile, raw marinated fish is a Bangkok street food classic, marinated with… fish sauce (sometimes fermented fish sauce), chili, garlic, lime juice, and herbs.

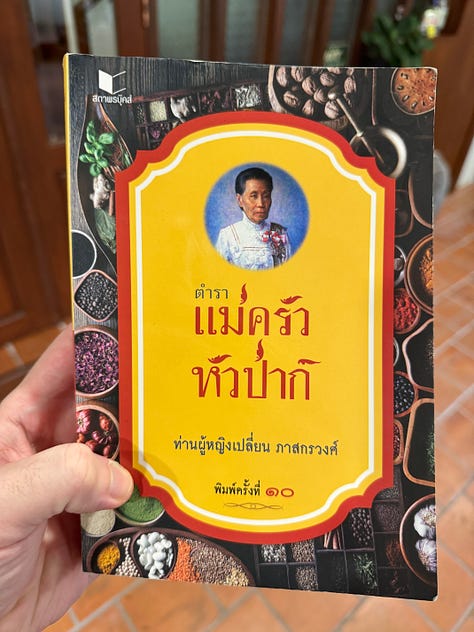

In both cities, these are old, much beloved dishes. And the similarities are pretty striking - just swap the soy sauce for fish sauce, and the vinegar for lime juice. It’s not too much of a leap of the imagination to suppose that perhaps in Thailand they then took that dressing and applied it to other dishes. There’s also other intriguing clues, such as this old Yam recipe calling for ‘Japanese Fish Sauce’, which is thought to have been a soy sauce cut with fish sauce:

Then on the Hakka side, the explanation would be pretty simple. Meizhou, a major Hakka cultural epicenter, shares a river with Chaozhou, and is just up the river from Jieyang (a major Teochew city). There’s a ton of contact between Hakka and Teochew in that corner of Guangdong - I mean, Hakka are the second most common group in Chaozhou after the Chaozhou people themselves.

So… where’s the Yam actually from?

Besides us quickly reaching the limits on our abilities here (some proper academic out there, please accept the baton), there’s another issue with theorizing about this stuff too much.

The problem? Directionality.

Because like, connection is relatively easy. I think it’d be a fair guess that all four of these dishes - Thai Grilled Beef Yam, Hakka Beef Yam, Thai Yam Sot, Teochew Sheng Yan - that all four of these are connected.

Origin is not easy, because while Chaozhou obviously influenced food in Southeast Asia, Southeast Asia also influenced food in Chaozhou. Because of course it did, right? After all, Chicken Tikka Masala was invented in Glasgow…

But an even larger issue is that all of this could have some hidden common ancestor, as all of these languages - Thai, Teochew, Hakka - they all have at least some roots in Old or Middle Chinese. And it’s this possibility that has an even higher probability to break my sanity. For example, that aforementioned old cookbook?

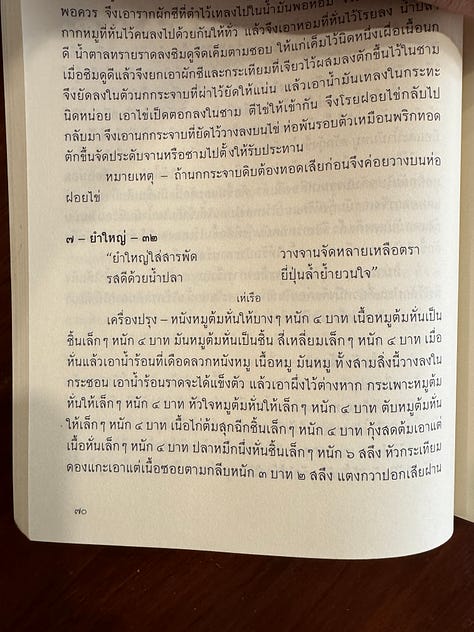

In it, they refer to that marinated raw shrimp dish as a ‘goi’:

Which is sort of interesting, because I personally usually associate the word goi with the raw beef salads that you can find up in the rural, Lao-speaking Northeast region of Isaan:

But here’s where it gets really interesting – in south Vietnam there’s also very similar stuff called Gỏi (this category of food is referred to as Nộm in the North, and it similarly translated into English as ‘salad’). The cool thing about delving into food history in Vietnam though, is that they classically used a variation of Chinese script called Chữ Nôm (in Chinese, Nanzi 喃字), so… they had a character for it:

This character corresponds with the Middle Chinese character on the top right, which historically referred to a dish of raw sliced meat. The Middle Chinese reconstruction of the character should sound roughly like ‘kuai’, but feel free to parse it yourself. This character then is seen in Korea to similarly refer to hoe (회), raw sliced marinated Sashimi, before also arriving in Japan. This, historically, referred to marinated raw meat and fish (thought by some to be the precursor to modern Sashimi), but over the years began to refer to dishes - a little like Thai Yam, perhaps! - that were dressed with similar ingredients. The dish that’s most famous for using this Kanji today is Namasu, which is a simple salad of daikon and carrot:

…this shit is getting fractal.

But then, where do we stop? We’ve got to put a pin on this somewhere, lest fall down a Sagan-esque rabbit hole:

Okay.

Thai salads are from Thailand.

Your "Italian Noodle Salad" hit me right in the "Snickers Salad" Bullseye.

There's a whole discussion about the "salads" to be found in the universe of the Northern Prairie Church Cookbooks of America now that Minnesota food is breaking the surface over here.

I have recently run across "Cream Cheese Donut Salad" (it has sliced grapes) and the Snickers salad is a popular melange of Granny Smith apples, sliced Snickers bars and Cool Whip or marshmallow fluff.

I swear I'm not punking you.

So from the fact that lots of the translations you are looking at come from people with their brains in the 19th century/early 20th - when "chicken-mayonnaise" and "chicken salad" were the same thing... of COURSE they called Laab "salad".

FWIW - My own food history poking around is telling me that any chopped mixture that is served COLD gets the salad designation. So the mixed rice dishes that were emerging were not salads. Remember the consternation and astonishment America experience at the innovation of hot dressings on cold salads!

Anyway - so much fun as always!