63 Chinese Cuisines: the Complete Guide

Not one cuisine, not eight, but many more. Our best shot at a comprehensive-ish guide.

One country, one cuisine.

It’s a model of food that really underpins how people tend to think about, organize, and categorize food. Search Google Maps, and your local eateries are bound to be arranged into “Thai” or “Italian”. Hop over to Taste Atlas, and you’ll find little country flags next to each article. On Reddit’s /r/cooking, it’s practically a semi-annual tradition to see someone attempting to make ‘food around the world’, dutifully hopping around the globe nation-state by nation-state. When Good Mythical Morning guesses where a certain dish is around the world, they throw a dart at a map divided into… countries. These divisions can even turn into a political project: food slotting in right there next to the national anthem and the flag emoji.

And in fairness, it’s certainly not complete bullshit. Borders set trading networks, so they often set what ingredients are available. Borders (often) set a language, so they set the linguistic pathways of how recipes spread.

But at the same time, it’s… kind of bullshit, right? Like, people in New York eat much more similarly to people in Toronto (or maybe even Sydney!) than they do to people in New Orleans. Geography matters. Culture matters. And these things quite often don’t neatly align to the various colors on the map.

And it’s in China, perhaps, where the one country, one cuisine model goes to die most violently. Sit Cantonese food next to Sichuan food, and the absurdity becomes aggressively spectacular:

And so, if you satiate your curiosity with a quick Google, you’ll often find people saying that “China doesn’t have one cuisine, but eight”.

“The Big Eight”

We could maybe even turn it into a little jingle.

“Cantonese, Sichuan, Hunan, Jiangsu, Zhejiang, Fujian, Shandong, and Anhui.”

The ‘eight cuisines of China’ — it’s a fun little bit of food trivia. I feel like when you’re new to the sport of Chinese food, it’s a fresh new model that can easily graft in and replace that tired, old one country, one system framework.

There’s other resources online that go into detail about The Big Eight. Personally, I don’t really want to dwell on the thing — after all, even if you’re fresh to a sport, I’m not a big believer in starting with bad form.

As you might be able to gather, I’m not exactly the most massive fan of the trope. I mean, the food’s good, of course. But there’s… a couple of issues:

The most obvious, glaring problem is the incompleteness. Take, for example, one of the most famous Chinese restaurants in America: Xi’an Famous Foods. The Anthony Bourdain favorite, the Millennial Hipster darling. People fell in love with their Roujiamo (“lamb burgers”); their slippery liangpi became a New York food sensation. They put Biang Biang noodles on the American food world map.

So where is Xi’an on this map?

Oh.

Like… the map’s overlooking not just Guizhou and Guangxi, it’s overlooking literally the entire North of the country. No Lanzhou Hand-pulled noodles, no Peking Duck.

What’s going on here?

The missing context, I think, is that ‘The Big Eight’ was never meant to be an exhaustive list of all the cuisines of the country. It was a somewhat haphazard extension of the so-called “Big Four” banquet traditions of imperial China: Cantonese (粤), Sichuan (川), Shandong (鲁), and Jiangsu (苏). The reason why The Big Eight contains Cantonese and not Yunnan isn’t because people in Yunnan don’t have a unique cuisine — it’s because Cantonese had an establish system of banquet presentation that was enjoyed by the merchants and the Mandarins of the Qing dynasty, and Yunnan didn’t.

This cultural background is sort of… implicit knowledge for a lot of foodies in China — implicit knowledge that I don’t usually see translated into English. So, there you have it.

But at the same time? I don’t think it’s exactly fair to tear down The Big Eight without building something to replace it. After all, it’s still a better starting point than One Country, One Cuisine! It’s just incomplete.

But then… if not eight, how many cuisines are there?

I’ve never seen anyone attempt to count.

So, we attempted to count.

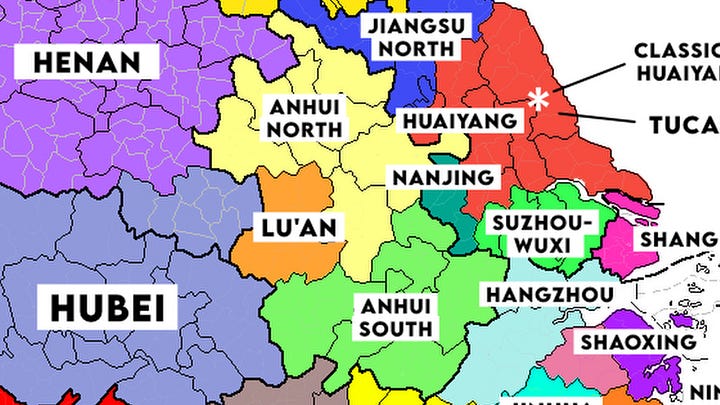

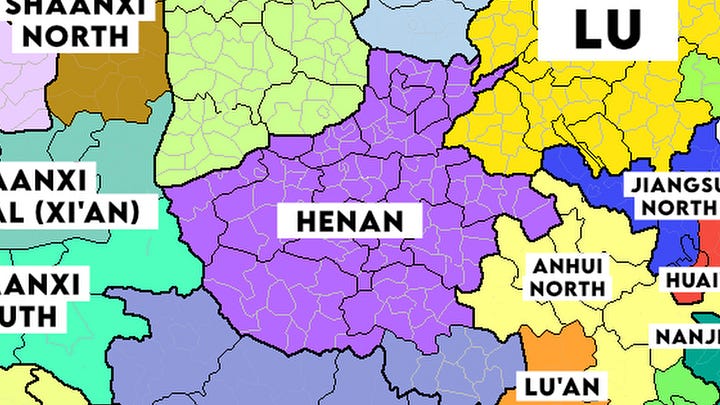

The 63 Cuisines of Mainland China

Welcome to the project that drove me to the edge of my sanity.

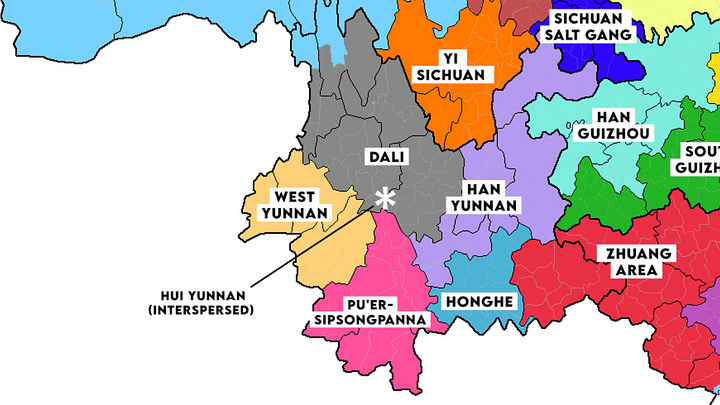

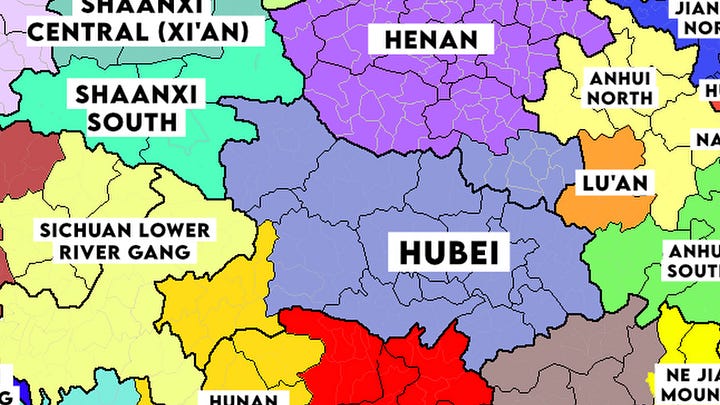

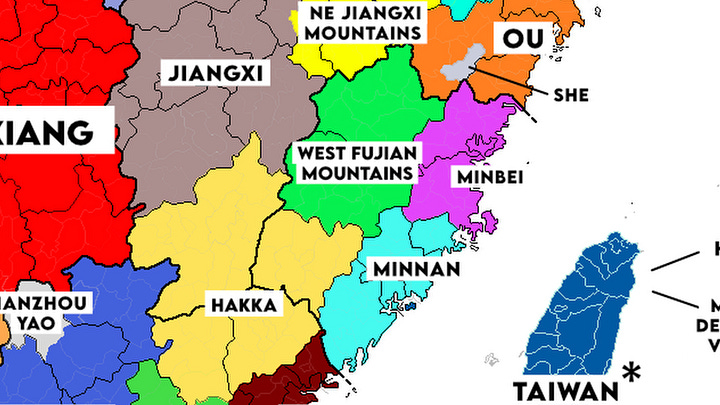

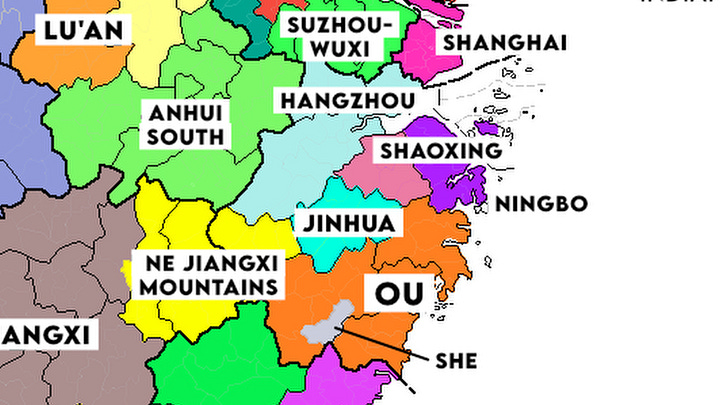

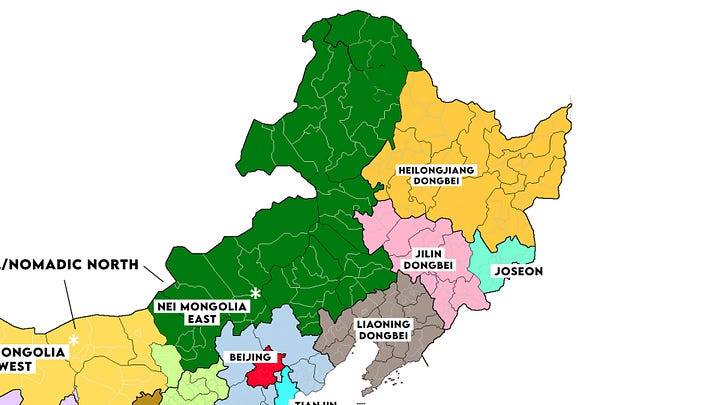

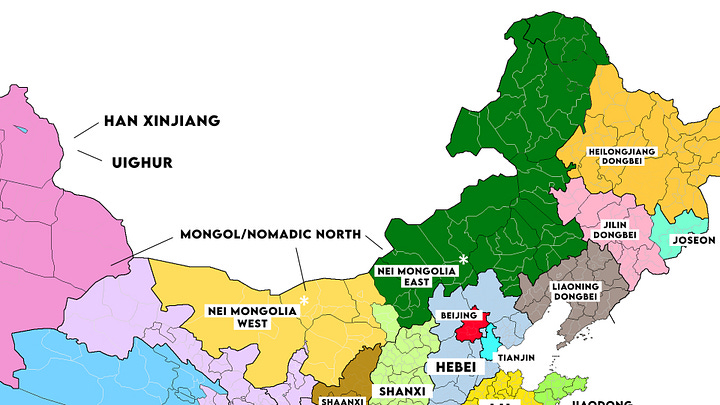

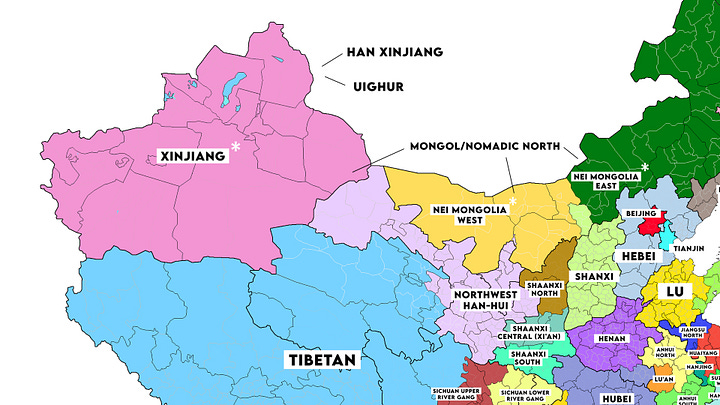

Here’s our map:

Here’s a full(er) res copy. Save it, peruse it, share it, whatever.

This post is… a little bit of a knowledge dump. I hope it can be a resource. It’s definitely gunna be too long for email, and probably too long to read in a single sitting. Think of this as the coffee table book of the Chinese Cooking Demystified Substack — it’s here to open, browse, and poke around from time to time.

Further, I also want to emphasize that we tried to come to this project from a position of humility. How to define the boundary of a ‘cuisine’ is not obvious. I went into (probably overly excruciating) detail about our methodology in the accompanying video, so I won’t re-hash too much of it here. Our rules of thumb were:

Passing The 50% Rule. If you’d estimate that more that 50% of the dishes are ‘unique’, and the dishes that remain often have different versions, it’s a separate cuisine.

Culinary Self-Determination. Do the people themselves (particularly the food world) make a distinction between cuisines? E.g. people in Louisiana are quick to make a distinction between Cajun food and Creole food, so to us this would be two distinct cuisines - even if the differences may not be overly obvious to an outsider.

Failing the ‘Mutual Intelligibility’ test. Imagine an old, talented home cook from one area. Would they be able to recreate a dish from another area solely from taste, without looking anything up?

‘Culinary Continuums’ must be broken somewhere. A little like dialect continuums in linguistics, there can often be small changes in food between neighboring towns and cities - that then morph into large differences if you zoom out and look at either end of the continuum. Boundaries will ultimately arbitrary.

There will likely be a lot of contention about some of these boundaries, and there’s absolutely stuff that we missed. We’re also personally the most familiar with the South of China, so differing opinions and viewpoints are more than welcome.

All we wanted to do was improve on the big eight.

Note: Taiwan is included in the below maps because the lowland regions have been part of the China proper social-ecological system since the 1600s. As we discuss in our section on Taiwan ‘outside of mainland China’, this was then layered with other provincial Chinese cuisines as KMT forces fled to the island. It implies nothing about the political status of Taiwan.

(we also don’t get in any trouble this way)

Guangdong Province

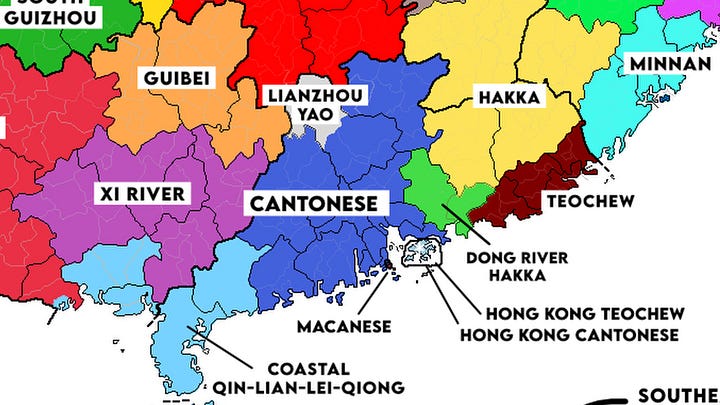

We divided Guangdong into six cuisines (nine if you include Macau and Hong Kong).

Cantonese is, of course, by far the most well known of the six and needs little introduction.

And yet, at the same time, I think the cuisine can sometimes be a bit misunderstood. If you ask ten Cantonese chefs what the ‘essence’ of Cantonese cuisine is, practically to the man they’ll reply ‘keeping the original flavor’. It’s a motto that works pretty well within a Cantonese cultural context: as a way to proudly distinguish yourself from the Sichuan and the Hunan. Less realized, I think, is that in an international 21st century context, the trope communicates as a self-own more than anything — a bit like bragging about how wide your city’s downtown freeway is: “okay, got it, Cantonese food is a stuffy old cuisine that doesn’t know how to season things”.

And while it’s certainly true that Cantonese food opts not to impress with chili peppers by the fistful, this isn’t exactly Scandinavian hospital food either. Black fermented soybeans feature prominently, ditto with other fermented sauces. The use of dried seafood and mushrooms — practically umami concentrates — is ubiquitous. Hell, on an international scale, they might even be less afraid of the chili pepper than their reputation might suggest…

Instead, to me, Cantonese cuisine is all about The Democratization of the Haute. In the age of Imperial China, there was a sort of ‘national cuisine’ of the elite called Guanfu cuisine, which we’ll touch more on in our discussion on Beijing. During the 19th century, the merchant class in Canton grew in breadth and depth, and the food they ate ended up borrowing quite a bit philosophically from that Guanfu tradition.

And what was that tradition all about? Well, outside of simply showing off (the food of the elite forever rhymes), that cuisine particularly loved the playful manipulation of form.

To illustrate, the Cantonese Pearl River is the land of two fish - the lingyu (Dace) and the wanyu (Asian Carp). And so, yes, they do sometimes opt to keep that ‘original flavor’ to make sashimi — and Shunde-style Sashimi is quite delicious. But you can also chop some fish up real fine and use it as a stuffing (e.g. for chilis). Or you can take that paste, mix it with egg white, deep fry it and get a dead wringer for tofu. Or you could pan-fry that fish, shred it, and toss it in a water chestnut starch-thickened soup and make a ‘congee without rice’.

You see this sort of thing again and again in Cantonese food — it’s a fun cuisine. I mean, on some level isn’t the entire Dim Sum cart “stuff stuffed in stuff, stuffed inside of other stuff”? What makes Cantonese food awesome is that every time you’re lounging al fresco at a Daipaidong, every time you’re grabbing steamer baskets from the Dim Sum house… you’re eating an echo of the Qing Dynasty elite. And that, I think, is a beautiful thing.

Of course, geographically speaking, this cuisine — together with Cantonese language and culture writ large — is quite bound to the Pearl River system. It starts from the delta smack dab in the middle of the province and continues westward. You can find Cantonese speakers all the way into the Guangxi province next to the Vietnam border, but hop one or two peninsula to the east of the Pearl River Delta and you’re already starting to get into a very different linguistic and culinary zone.

To the east, there are two primary cuisines: Teochew and Hakka. Teochew (Chaozhou, in Mandarin) may appear similar to Cantonese at first blush — neither cuisine features the chili pepper very prominently — but any apparent similarities are quite surface level. There’s not much crossover in dishes, and what dishes they do share often have different versions. Cantonese meals are based around white rice; Teochew meals can be served with rice or they can equally be served with mue (糜), a thin rice porridge often paired with salty preserves. Teochew language is mutually unintelligible with Cantonese and more closely resembles the Min languages next door in the Fujian province.

With that said, Teochew and Cantonese have obviously had more than a little bit of contact over the centuries. Besides being not all that far apart, both cities were famed for their (rival) merchant classes. Both groups helped build the twin economic engines of Hong Kong (a bit more Cantonese than Teochew) and Shenzhen (a bit more Teochew than Cantonese). This is why Hong Kong fishballs are generally the Teochew style, and why you can find Teochew-style Cheong Fun variants on the streets of Chaozhou and Shenzhen.

Hakka, meanwhile, are a fascinating Chinese subgroup thought to have migrated over the centuries from the north of the country down into the south. Precisely why that was is hotly debated, but by the late Qing they nonetheless ended up settling down in the mountainous bits of Jiangxi, Fujian, and Guangdong. As migrants, they were often confined to land that was less productive agriculturally, and the sweet potato formed the foundation of the traditional Hakka diet. Historically, there was no love lost between Hakka and Cantonese - there were even wars fought over land in the mid 19th century.

These days however, that history is a distant memory. But Hakka food still bears some imprint of it - while rice is the modern staple, sweet potato features much more heavily than in Teochew and Cantonese. And - apocryphally, at least - a number of classic Hakka dishes are thought to have been forged from attempting to make wheat-flour based northern Chinese foods in a new land that didn’t really have much wheat (e.g. their stuffed tofu is said to be a dumpling equivalent, though I think it’d be fair to register that claim as… ‘debatable’).

Dong River Hakka, meanwhile, consist of Hakka communities in Huizhou, Dapeng (Shenzhen), and other bits scattered around the Pearl River Delta1. This is one of those ‘culinary self determination’ internal divisions, as Dong River Hakka is generally considered a distinct by many Hakka chefs. A reasonable argument could be made that the food in this area is really more of a cross between Hakka and Cantonese than a distinct cuisine per se, but admittedly we haven’t spent much time in the epicenter of Huizhou.

Returning back to the Pearl River system, as Cantonese moves to the west and into the hills, the food begins to change. Flavors become stronger, you start to see some echoes of non-Han influence (e.g. steaming in bamboo), and fermented ingredients start to appear more often than the Cantonese mainstay of dried ingredients. We drew the line between Cantonese proper and its more strongly flavored cousin (“Xi River” cuisine) at the province border, but a little east or west would also make sense. In the hills, we also chose to separate Lianzhou - an area with a good chunk of Yao people influence - out as a distinct cuisine.

The Coastal west of Guangdong shares a number of similarities with Cantonese, and could perhaps be lumped in with Cantonese if you were feeling lumpy. That said, the south of Guangxi along the gulf of Tonkin (Beihai), the lowlands of Hainan (Haikou), and the Leizhou peninsula in Guangdong (Zhanjiang) bear some striking similarities - this region sometimes being referred to as ‘Qin-Lian-Lei-Qiong’ (钦廉雷琼). The prominence of seafood would probably be the most obvious element of the cuisine to a traveler, but things are also starting to get a bit more heavily seasoned, ala the food in neighboring Guangxi. Their mixed rice dishes are also renowned - most famously the Haikou area’s chicken rice, which over the years became a favorite throughout Southeast Asia as well. Also interspersed in this area are also communities of Teochew speakers (lost on their way to Southeast Asia, perhaps?), which also influenced the food in a number of ways, most obviously with various rice products called he (籺).

Cantonese

Representative dishes:

Wonton Mee (云吞面). Top left. Wonton noodles, a Cantonese classic. Often served in soup, this version was ordered dry with soup on the side - smothered with dried shrimp roe, and oyster sauce to mix.

Dim Sum (早茶). Top middle. This particular dish is Siu Mai (烧麦), a pork and shrimp dumpling.

Cheong Fun (肠粉). Top right. Breakfast rice noodle rolls, topped with a seasoned soy sauce. There can be various stuffings, but are often rather subdued - this specific one is a bit of pork mince. Soy milk is a more common drink to go along with it, but if you’ve got a nice coffeeshop next door, why not?

Claypot Rice (煲仔饭). Bottom left. Much beloved Cantonese dish, complete with crispy rice (i.e. socarrat) at the very bottom. This one was topped with pork ribs and Cantonese sausage.

Char Siu Rice Bowl (叉烧饭). Bottom middle. Cantonese roast meats are iconic - from Siu Yuk Pork Belly, to Roast Goose, to Roast Duck. This is Char Siu BBQ pork, served with egg in a rice bowl and topped with seasoned soy sauce.

Double Boiled Soups (炖品). Bottom right. Cantonese cuisine is quite renowned for their tradition of soup making - this soup in particular is scallop with hairy gourd (瑶柱炖节瓜).

Teochew

Representative dishes:

Teochew Lushui (潮州卤水). Top left. Teochew Lushui (master stock) has a unique spice mix - including additions like lemongrass and galangal. Stewed goose is a very classic item (卤鹅) and the “lion-head goose” (狮头鹅) is particularly prized. This one is a plate of goose breast.

Mue (糜). Top middle. Pictured is a simple bowl of mue with its classic pickled pairings. The preserves that goes with Teochew mue congee are called giamzap (咸杂), meaning “various salty things”. Pickled daikon (菜脯) is the most classic.

Chinese Black Olive with preserved vegetable (橄榄菜). Top right. The most famous giamzap outside of the region is Chinese Black Olive. Pictured is a bottle of pickled mustard green with Chinese black olive (which, I have to say, is also fucking incredible topped over white rice as well).

Oyster pancake (蚝烙). Bottom right. The coastal southeast - from Chaozhou to Fujian - has a tradition of using sweet potato starch to make various kinds of pancakes, of which oyster pancake is probably the most famous. The most common variant in Chaozhou is (1) a round pancake with (2) eggs added and (3) fried until the edges are crispy.

Seafood congee restaurants. Bottom middle. Being a rocky coastal area, historically the region didn’t have much land for rice cultivation, leaning instead on the ocean. Pictured is a local congee restaurant in Jieyang city with fish and seafood laid out front. Choose your seafood, the kitchen whips it up, and you enjoy it next to some mue congee.

Guorou (裹肉). Bottom right. Common to the area are various forms of ‘rolls’ containing meat or seafood, rolled up in thin tofu sheets then steamed to form. This one in particular is a type of roll called guorou in Mandarin (裹肉, lit. ‘wrapped meat’) - cut into pieces, deep fried, and served with a sweet fruit sauce.

Hakka

Representative dishes:

Stuffed Tofu (in soup) (酿豆腐). Top left. Hakka cuisine loves its stuffed stuff, with tofu being the most famous. It comes in many different shapes, fillings, and ways of serving. Pictured is a variety stuffed with minced pork and salted fish, served in an (excellent) pork broth.

Mixed ‘Yan’ Hakka Noodles (腌面). Top middle. While you can find various types of “Hakka Noodles” all around the world, pictured is the OG version - a simple and delicious affair of noodles mixed with lard, fish sauce, and deep-fried garlic, served along side a bowl of pork bone soup.

Mixed ‘Yan’ Beef (腌牛肉). Top right. Mixed, or ‘yan’ dishes feature heavily in Hakka cuisine. In addition to the mixed noodles above, mixed beef is another common dish of its category. There are regional variations - pictured is a Meizhou sort mixed with garlic, chili oil, and Chinese fermented black soybeans.

Salt-Baked Chicken (盐焗鸡). Bottom right. Salt baked chicken is a Hakka classic that has a couple variants. The most traditional way of making it is baking an entire chicken (wrapped in paper) in a large wok of salt. The meat keeps well and is quite firm, as shown.

Taro balls and Daikon balls (芋头丸/萝卜丸). Bottom middle. Hakka cuisine loves its balls. Meatballs are obviously classic as well, but pictured is (1) a steamed Daikon ball made from mixing shredded Daikon with sweet potato starch and (2) Taro ball made in a similar fashion. Deep frying is also a popular route.

Faban, rice cupcake (发粄). Bottom right. Pictured is a fluffy rice cupcake called faban (发粄), colored with red yeast rice. In Hakka language, the latter character, ‘ban’ (粄), is a catch-all term that can be used to describe anything made from dough or batter - from cupcakes, to pancakes (麦粄), to dumplings (艾粄), to noodles (老鼠粄), and even jelly (草粄).

Dong River Hakka

Representative dishes:

Dongjiang-style Stuffed Tofu (东江酿豆腐). Left. In the Dongjiang region, this dish is most often panfried then quickly simmered sauce. In Hakka restaurants within more Cantonese cultural areas like Guangzhou, this is generally the version that you’ll find on restaurant menus.

Pork Belly with Preserved Vegetable, Meicai Kourou (梅菜扣肉). Middle. Meicai Kourou, preserved mustard green with pork belly, is a Hakka classic dish for banquets and festivals. The pork belly is poached, deep fried, sliced into large pieces, then steamed with preserved mustard greens. The one shown here also has taro pieces steamed in between the slabs of pork belly to help absorb the entirely of the flavorful sauce.

Three Cup Duck (三杯鸭). Right. “Three cup’ is a flavor profile originating in Hakka cuisine, which classically braising with one cup each of rice wine, soy sauce, and toasted sesame oil. Three cup chicken is probably the most famous one outside of Hakka region but other poultry can also be used such as duck, goose, or pigeon.

Lianzhou (Yao)

Representative dishes:

Beef Pancake (牛肉糍). Left. A deep-fried stuffed pancake with a beef filling mixed with shredded daikon, chili, and garlic scape. It uses a shallow ladle as a mold, sandwiching beef in between layers of batter (made from a mix of mashed rice, sweet potato, and taro).

Smoked jerky (牛肉干). Middle. The Yao people traditionally would preserve meat via smoking, an approach much more common to Hunanese than Cantonese cooking. Popular in the area is a beef jerky, made by grilling, smoking, then drying marinated beef. The jerky is then eaten by thinly slicing and steaming, or alternatively stir frying with chilis, pickles, and/or black fermented soybean.

Chili beef noodle soup (星子牛肉面). Right. A spicy and sour beef noodle soup topped with lacto-fermented mustard green, pickled chilis, pickled daikon, minced garlic, and chili sauce.

Coastal (Qin-Lian-Lei-Qiong)

Representative dishes:

Duck rice (鸭仔饭). Top left. In addition to the famed Chicken Rice (more on this below), other poultry like duck or goose also feature prominently in the category. Cooking method is similar: the poultry is poached, then the rice is cooked together with the bird’s rendered fat and the cooking liquid from poaching. In Leizhou, the set comes with a bowl of duck soup as well.

Wet Spicy Beef (湿辣牛肉). Top middle. A newer addition to the area’s BBQ scene, ‘wet spicy beef’ are grilled beef skewers dipped in a spicy (sometimes coconut milk-laced) sauce.

Seafood Rice Noodles (海鲜捞粉). Top right. Seafood a major aspect of the area’s cuisine - from stir fries, braises, to snacks, and rice noodles. Pictured is a flat rice noodle (hor fun) served in a shellfish-based stock topped with various seafood.

Chicken rice (鸡饭). Bottom left. The origin of the world-famed Hainan chicken rice. The variants in the mainland tend to be simpler than its Southeast Asian cousins, opting for somewhat different dipping sauces. The version in the picture was served alongside a sand ginger-soy sauce dip.

Beef & Wild Betel Rice Cake (机粽饼). Bottom middle. This chewy rice cake originated from Teochew migrants to the area. While some of these cakes can be quite simple, pictured is a sweet and savory version with beef and wild betel (蛤蒌叶), an herb which adds an herbaceous and peppery punch.

Layered rice cake (簸箕炊/水籺). Bottom right. This plain layered rice cake is popular throughout the region, with different names and different toppings. It’s made by steaming white rice batter in layers using a bamboo tray or metal sheet. It can be eaten alongside garlic soy sauce, bean paste, garlic oil, Chinese chive oil, or peanut oil; and topped with toasted nuts, preserved mustard green, pickled daikon, minced pork, and/or dried shrimp.

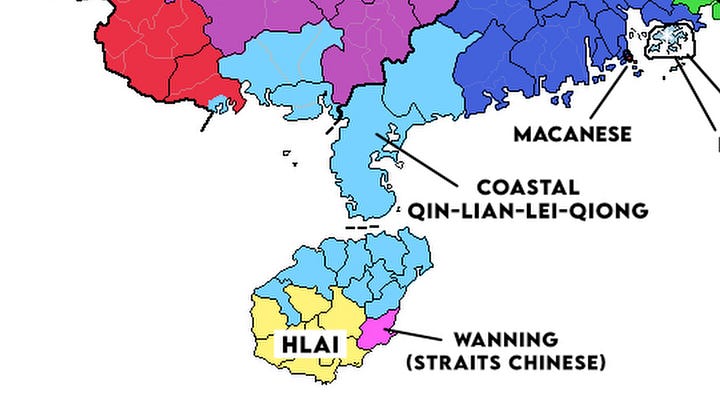

Hainan Province

The largest city in Hainan, Haikou, is very much within the Coastal (Qin-Lian-Lei-Qiong) cuisine discussed above. That cuisine was listed under Guangdong mostly for convenience, as Northern Hainan might very well be where the center of gravity is there.

In the south — around the tourist haunch of Sanya — is a very mountainous region that was traditionally the home of the Hlai ethic group, a Tai–Kadai speaking ethnic group that’s fascinating in their own right. While these days most of the food commercialized along the coast will serve up tourist-focused fair like coconut chicken hotpot (a Shenzhen invention), you can still find Hlai restaurants within the mountainous interior.

Around Wanning — Xinglong, specifically — there’s a fascinating community of Indonesian Chinese that fled to the mainland to escape Suharto’s purges in the 1960s. We’ve personally never been to the city, so it’s a little difficult to parse how organic the cuisine is to that pocket - or if it’s simply a sort of tourism production. We’ll discuss Straits Chinese later in the post.

Hlai

Representative dishes:

Leaf Banquet (长桌宴). Left. Leaf banquet or “long table banquet” is a festive ritual for Hlai people, with colored rice serving as the centerpiece. Dishes to serve alongside would be their local style of blood sausage, braised palm hearts, grilled fish, etc.

Stir fried banana blossoms (炒芭蕉花). Middle. Banana blossom’s an ingredient eaten widely throughout the tropical Southeast Asia, and Hainan is no exception. In addition to stir frying (pictured), it can also be braised or stewed with meat.

Fermented fish (鱼茶). Right. Similar to other Tai–Kadai groups, Hlai also has a penchant for the sour — notably, fermented fish and fermented meat. This version is freshwater fish fermented with salt and sticky rice — after fermentation, it can be eaten straight or steamed.

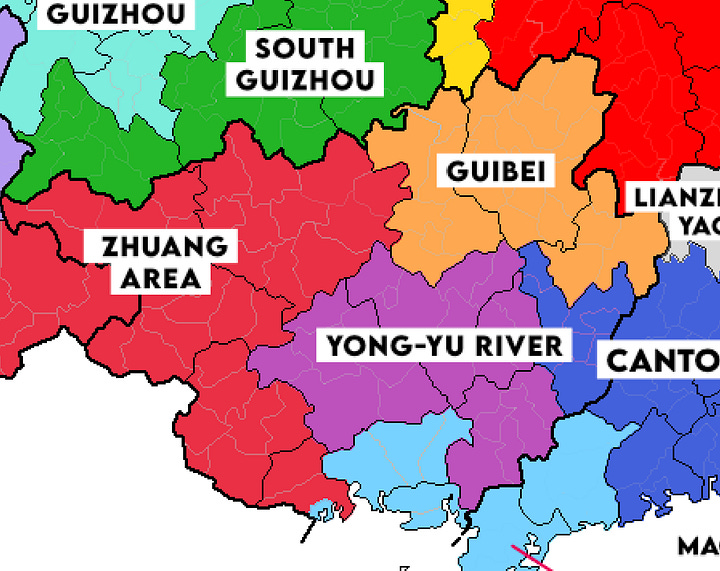

Guangxi

The Yong-yu River is the major western portion of the Pearl River system, and as such shares some techniques and philosophies with Cantonese. I sometimes refer to the cuisine as ‘Cantonese’s wilder, kinkier cousin’, and it’s comparatively much less afraid of spicy and sour flavors than the eastern portion of said river system.

Internationally, it’s a cuisine that’s a bit infamous for its tradition of dog meat — in particular, the city of Yulin. And while I don’t partake in eating dog myself, I do have to hand it to the Yulin people: lifting one culinary middle finger high and proud against the collective indignation of the entirely of the west, and your other against the collective disdain of the cosmopolitan cities of Shanghai and Shenzhen? For a small city, that takes some guts. We should all try to learn a little from Yulin.

Moving west, is the Zhuang Area, which extends into Yunnan and, arguably, Vietnam. The Zhuang are a highly sinicized Tai-speaking ethnic group that are thought to have been the province’s original inhabitants. This is one of those ‘culinary continuums’ where it’s often not completely clear with where this region begins, and the Yong-Yu River ends. The food, however, is starting to look radically different from Cantonese, with incredibly strong local ethnic influences — particularly love of sticky rice.

Guibei is a stunningly gorgeous pocket of the country, and was difficult to categorize. There’s similarities with both Yong-Yu River (rice noodle heaven) and South Guizhou (a love of the chili pepper), but has enough unique dishes - e.g. Liuzhou Snail Noodle soup, incredibly popular well throughout China these days - that we marked the area as distinct.

Yong-Yu River

Representative dishes:

Ol Buddy Noodles (老友粉). Top left. The laoyou ‘ol buddy’ flavor profile is a mix of garlic, sour bamboo shoot, pickled chili, and Chinese fermented black soy bean. The original version of the dish was a pork noodle soup, but over the years rice noodles (pictured) also became quite common, and its popularity inspired many other dishes like ‘ol buddy’ rice cakes, snails, stir fried beef, etc.

Lemon Duck (柠檬鸭). Top Middle. A classic Guangxi truck driver dish that over the years became signature to Nanning city. It consists of a braised duck that leans on very Cantonese-feeling technique at first blush, but seasons heavily with preserved lemon and Guangxi’s dried Murraya fruit (鸡皮果).

Paper Wrapped Chicken (纸包鸡). Top Right. Actually an invention from the city of Ngchow (what we selected as westernmost portion of the Cantonese culinary sphere), but quite popular in Nanning as well. This chicken is first marinated, then wrapped with a type of paper meant for culinary use called yukou paper (玉扣纸). It’s then deep fried low and slow — the final result being texturally similar to roast chicken (albeit one that’s been cooking for a while in its own juices).

Breakfast Rice Noodle Soup with Guangxi-style Char Siu (叉烧粉). Bottom left. A simple breakfast of pork stock and flat rice noodles. It’s topped with an array of sour and spicy pickles, together with Guangxi style Char Siu BBQ Pork - a heavily spiced and deep fried Char Siu variant.

Guangxi-style Cheongfun (广西肠粉). Bottom middle. Similar at its core to the classic Cantonese cheongfun rice noodle rolls, but with bolder flavors and topped with a very ‘Yong-Yu’ herb — purple perilla leaves.

Nanning-style Zongzi (粽). Bottom right. Yong-Yu River Zongzi — sticky rice dumplings — are similar in style to western bit of the Cantonese world, i.e. around Ngchow and Zhaoqing. This swath uses sticky rice and shelled mung beans as a base, but what makes the Nanning variant stand out is the addition of kourou (扣肉) — deep fried-and-braised tender slabs of taro and pork belly slab. The package is then tightly wrapped in leaves and cooked for hours.

Guibei

Representative dishes:

Luosifen, Snail Rice Noodle Soup (螺蛳粉). Top left. The Liu River that flows through Liuzhou city also brings in one of the most important ingredients to the city — fresh water snails the famed luosifen noodle soup. The soup consists of a bowl of rice noodles, served in a snail stock, and topped with sour bamboo shoots and chili. There’s a meme that the dish is ‘stinky’ but that’s mostly a function of low quality mass produced or packaged varieties: the luosifen authentic to Liuzhou doesn’t have much of an odor at all.

Guilin Rice Noodles (桂林米粉). Top middle. Guilin rice noodles (at least in Guilin itself) is served as a mixed noodle with soup on the side. The rice noodles are mixed with fermented bamboo shoot, peanuts, scallion, and topped with chili oil and crispy deep fried pork belly (锅烧).

Horse Meat Rice Noodles (马肉米粉). Top right. …not a typo. Yes, horse meat. A quite traditional dish, this rice noodle is served topped with a cured horse jerky, within a horse bone broth.

Beer Fish (啤酒鱼). Bottom left. If a traveler finds themselves in the (gorgeous, admittedly) tourist town of Yangshuo, beer fish may be a their first introduction to the “local food”. While undeniably a bit of a tourist dish, it’s representative nonetheless of certain characteristics of the region: love of chili, love of fish, both cooked in the town’s special local tea tree oil.

‘Eight Treasure’ Beef (牛八宝). Bottom middle. As a restaurant concept, “Eight treasure beef” joints will lay out various parts from a cow for you to choose from. Sour and spicy, the dish is either eaten wet as a hotpot or fried up dry as a dry pot.

Sour Tripe (牛肠酸). Bottom right. Similar in form and philosophy to Cantonese niuza beef skewers, albeit seasoned much more heavily in the direction of spicy, and, well, sour. The skewers are often eaten ‘omakase-style’, with eaters gathering around a vender serving directly out of a big pot of bubbly red soup.

Zhuang Area

Representative dishes:

Five Color Rice (五色糯米饭). Left. Culturally, the five colors — black, purple, white, yellow, and blue — each represent their own sacred meaning to the Zhuang people. Traditionally, this colored rice is eaten for rituals and important festivals, but nowadays you can find it at markets throughout the year. It can be eaten straight, formed into a rice balls, pounded into rice cakes, or eaten with sausage and pickles. These days, it’s not unheard of for Han people in the area to turn it into a sort of Cantonese-style stir fried sticky rice, complete with pork, sausage, peanut, and scallion.

Longlin Chicken Rice Noodle Soup (隆林鸡粉). Center. This is a noodle soup that’s suspiciously similar to pho ga in Vietnam — though perhaps not overly surprising as the town of Longlin isn’t all that far from the Vietnam border. The chicken rice noodle soup can be topped with herbs and/or sour and spicy pickles.

Yaba, Wrapped Duck (鸭把). Right. Yaba, literally meaning “duck handle”, is a specialty around the Hechi city. It contains duck meat, duck stomach, pear, cucumber, Thai basil, all wrapped together with ginger leaf. The dipping sauce is made with duck blood (OG version uses raw blood), ginger, and sour pickles.

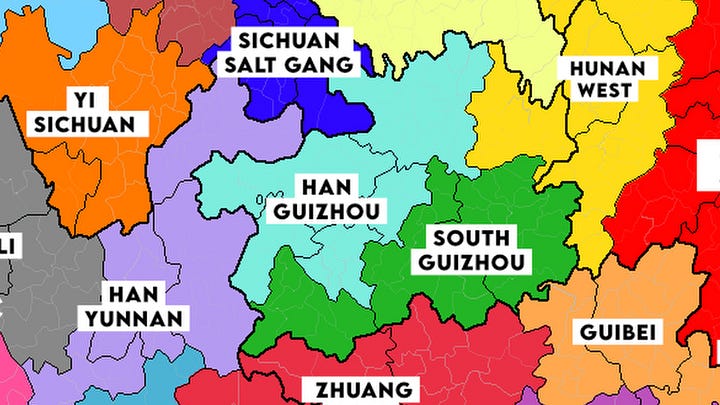

Guizhou

Guizhou is a difficult province to map, as altitude is a much stronger predictor of food than latitude and longitude are. It’s an incredibly rugged, mountainous province that historically served as an imperial outpost, a pit stop on the way to Yunnan and its productive tin mines. Han Guizhou consists of the lowlands, and today is centered around the cities of Guiyang, Zunyi, and Anshun.

The food is heavily seasoned. There’s an old, increasingly worn out saying in China that “the Sichuanese can handle their heat (四川人不怕辣), that the neighboring Hunan province isn’t afraid of their chilis (湖南人辣不怕), but that people from Guizhou are afraid of food that’s not spicy enough (贵州人怕不辣)”. I’ve reluctantly repeated it on our channel before, though I’m not even sure how accurate it is (I might lean towards lower-river Sichuan as being the hottest, and I’ve also seen the quip presented in different ways).

Regardless, it certainly belongs to the category — you could definitely use Sichuanese food as a mental starting point. But layered onto that are influences from ethnic groups from the surrounding mountains, particular with regards to various ferments: Fermented Tomato Catfish soup being probably the most famous. If Yunnan food is a chunky stew of different ethnic cuisines, you could maybe think of Guizhou food as something a bit more blended.

Still, once you get up into the mountains — in Dong, Bouyei, and Hmong (Miao) Guizhou — things become increasingly less “Han”. Dong Guizhou, for instance, has flavors like fermented shrimp and niubie — flavors that, to me, harken much closer to Laos and Thai Isaan than they do neighboring Sichuan. While these multi-ethnic highlands are ubiquitous throughout the province, they are particularly concentrated in South Guizhou.

Han Guizhou

Representative dishes:

Anshun Flaky Baozi (安顺破酥包). Top left. The city of Anshun was an important military outpost since Ming Dynasty, and as such has strong Han food traditions - these flaky Baozi being among them. The flakiness comes from laomian (Chinese style ‘sourdough’) and laminated with lard. Pictured is our favorite filling - the “three delicacies” of scallion pork, washed bean paste, and perilla seeds.

Goat Rice Noodle Soup (贵州羊肉粉). Top middle. A popular rice noodle soup throughout Guizhou, and has since spread all across China. It’s made by stewing large chunks of goat meat and organ in with a special mix of spices (a spice pouch of 36 spices, give or take). Once done, the goat meat’s taken out, wrapped up with cloth, and pressed to firm up before thinly slicing into thin pieces. Upon ordering, the cook’ll quickly blanch rice noodles in hot water, pour over the goat stock, and top with few pieces of goat meat and organ. Goat rice noodle soup has four major schools in Guizhou – Shuicheng (水城), Xingyi (兴义), Jinsha (金沙), and Zunyi (遵义), respectively. Jinsha claims to be the original. The one in Shuicheng features fragrant chili oil and chili crisp, Xingyi tops with a special fermented wheat sauce, and Zunyi mixes deeply toasted chili flakes into the soup itself.

Douchi Hotpot (豆豉火锅). Top right. Perhaps could be thought of as half a hotpot, half a sauce. The base of the pot is made with minced pork, lightly fermented soybeans, and a preponderance of chilis. Upon ordering, the pork’s fried at the table to first render out some oil, then fried together with said chilis and the titular fermented soybean. Pork stock is then added, and the meal continues as a hotpot would. As the concoction reduces, you complete the meal by mixing the progressively thicker soup over rice.

Deep Fried Tangyuan with Fermented Mustard Greens (酸菜炒汤圆). Bottom left. This dish is a bit infamous, belonging to the so-called “dark cuisine of China” (黑暗料理) according to the Chinese internet. It consists of sweet, black sesame filled sticky rice balls, deep fries them, and then stir-fries that with fermented mustard greens and dried chili pepper (and seasons with a non-insignificant quantity of MSG). It feels weird because it is kind of weird. I’d grant that it might be closing in on the Chinese equivalent of fair food, but it’s also - in my humble opinion - actually quite delicious.

Si Wa Wa (丝娃娃). Bottom center. A spring pancake rolled up with an array of fillings including vegetables, pickles, and tofu products… eaten together with a characteristic sauce made from a fermented sour soup. The name itself (lit. ‘silk baby’) refers to wrapping a baby in swaddling cloths - sort of a stretch, but hey.

Breakfast Sticky Rice Bowl (贵阳糯米饭). Bottom right. The breakfast sticky rice bowls ubiquitous to the morning streets in Guiyang city were originally a sticky rice balls - something meant for the road and mixed with lard, soy sauce, and Cuishao, Guizhou-style cracklins. Over the years, it become increasingly common to see it in bowl form, with an ever increasing quantity of various toppings… kelp salad, shredded potato, deep fried peanut, fishwort, pink pickled daikon, sweet Cantonese sausage, etc etc etc.

South Guizhou

Representative dishes:

Fermented Tomato Catfish Soup (酸汤鱼). Left. Originally a Hmong and Dong people’s way of eating, the fermented tomato base make use of small, sour local tomatoes (an incredibly sour cultivar called ‘wild tomatoes’, whose botanical name still eludes us). When cooked, it’s often mixed with sour fermented chilis and a ‘white sour soup’ that’s made from fermenting rice cooking liquid. It can be a base for cooking meat — catfish hotpot, most famously — or alternatively a starting point for a rice noodle soup (酸汤粉).

Fermented Shrimp Paste Beef Pot (虾酸牛肉). Center. The most famous fermented shrimp paste — “xiasuan” — is from Dushan county in south Guizhou. Xiasuan consists of a mix of small fresh water shrimp, fermented with chili and sticky rice wine. The most classic way of eating is to stir fry it with beef and serve as a dry pot. Other ingredients can then be fried up together from this base such as konjac jelly, lotus root, potato, etc.

Niubie (牛瘪). Right. Another ‘infamous’ dish that perhaps belongs to Chinese internet’s “dark cuisine hall of fame”. This dish belongs to a category of dish called bie or pie. It’s made by feeding a cow or goat a number of herbs before slaughter, then collecting them from the first stomach immediately after killing the animal. This digested herb liquid is then used as a base, into which the meat and organs from the animal will then be added. Bie appears in many contexts throughout the Southeast Asian Massif, but in Guizhou is often served in hotpot form. In my personal opinion, the Guizhou version is less challenging than the above description might have you believe — it’s more herbaceous and less bitter than some of its Southeast Asian cousins.

Yunnan

It’s probably fair to say that Yunnan has the most culinary diversity of any province in China. While our map contains a similar number of cuisines within Guangdong, that’s largely because we’re personally quite familiar with Guangdong. We also marked a lot of divisions within Zhejiang, but that’s because that province has some of the richest culinary history in the country (so, they like to delineate a lot of sub cuisines).

But really, when it comes to sheer density of distinct dishes? This is it. What Papua New Guinea is to language, Yunnan is to food.

The cause of the diversity is no mystery. Yunnan, historically, was (1) reasonably agriculturally productive, but at the same time (2) insanely difficult to traverse. It’s rocky all over, certainly, but doing a lot of the heavy lifting was the notoriously treacherous Hengduan Mountains — a range which historically cut Yunnan into three distinct trading networks.

West Yunnan traded just as much with Upper Burma and the Shan hills as they did with Kunming. Pu’er-Sipsongpanna had a similar relationship to the south, to Lanna in Thailand (Honghe is a bit of a hodgepodge of ethnic groups and is hard to categorize). The Kunming plateau was solidly within the Chinese trading network, and so Han Yunnan shows a number of similarities with Guizhou and Sichuan. Up in Dali and Lijiang, however, you’re really starting to see the influence of the Tibetan plateau (and a bit of influence from Tibetan traders as well).

And slicing through them all was the Hui Muslim caravans, which bridged the province not just internally, but also out to Burma, Thailand, and, of course, China proper.

If anything, the regional distinction on our map might be underselling the diversity. After all, Yunnan’s got 25 ethnic groups nestled inside — you could easily make the argument for 25 distinct cuisines.

Han Yunnan

Representative dishes:

Grandmother’s Mashed Potatoes (老奶洋芋). Top left. Potato being among the staple carbohydrates of rocky Yunnan, there’re countless ways the new world crop is enjoyed. Grandma’s mashed potatoes is probably the most famous - mashed potatoes mixed with sour pickled mustard green, common fennel, and smoked Chinese bacon.

Shao Er Kuai (烧饵块). Top center. A thin grilled rice cake which’s a popular street food item throughout Han Yunnan. Traditionally, it’s enjoyed topped with various sweet-savory sauces, toasted peanut and sesame, then wrapped around a youtiao deep-fried dough stick. Nowadays however, on the streets of Kunming, the thing can very much also function as a sort of… Yunnan rice batter burrito - stuffed with hotdog and fried egg, as pictured.

‘Fresh’ Fried Chicken (生炸鸡). Top right. Deep fried marinated chicken — named ‘fresh fried’ as it’s fried sans batter (and only a dusting of starch). Often served on top a bed of deep-fried mint.

Wandoufen (豌豆粉). Bottom left. A noodle jelly made by soaking, grinding, and cooking dry peas. There’s a number flavor profiles for wandoufen in Yunnan — the one pictured sits inside a a sauce of brown sugar vinegar, garlic water, soy sauce, and chili oil.

Little Pot Rice Noodles (小锅米线). Bottom center. Spicy ‘little pot’ rice noodle joints dot Kunming city, slinging thick rice noodles swimming in a base of pork stock, chili oil, Yunnan-style sour fermented mustard greens (酸腌菜) and a deep, fermented sauce called Zhaotong sauce (昭通酱).

Crossing the Bridge Rice Noodles (过桥米线). Bottom right. A general must for those on the Yunnan tourist gauntlet, there’s various theories on the origin of the iconic name. The one that makes most sense to us is that the requisite cooking time for all the items you put into your bowl of scalding-hot broth tableside — rice noodles, pork, ham, quail egg, etc — should be as short as crossing a small bridge.

Hui Yunnan

Representative dishes:

Niuganba Beef Jerky (牛干巴). Left. A widely beloved ingredient and originally a travel food for those traversing the rugged Yunnan mountains. Often eaten by thinly slicing then deep frying, or alternatively roasting over a fire and then pounding into strings. Incredibly fragrant, the oil that’s used to deep fry the jerky is quite valued in Yunnan home cooking.

Goat Soup (羊汤锅). Center. A giant pot of goat soup that can often be sighted these days at the province’s weekend farmers markets, it was traditionally a festival dish for both the Hui and the Yi people. It can be enjoyed in soup form, noodle soup form, or even hotpot form. Almost always topped with a big fistful of mint.

‘Big Crisp’ Beef Noodle Soup (大酥牛肉面). Right. The name ‘big crisp’ (大酥) to a cooking technique of first deep frying beef, followed by cooking in a braise flavored with a deeply savory fermented sauce (like Tangchi sauce or Zhaotong sauce) and a spice mix based around Star Anise and Tsaoko. It can be served directly as a dish or ladled over a bowl of noodle soup, like pictured.

West Yunnan

Representative dishes:

Wa People Shouzhuafan (佤族手抓饭). Top left. Pictured is a festive leaf banquet of the Wa people, featuring their beloved fermented soybean cake (also found in North Thailand and Shan State Myanmar) fried in minced pork and lard, cured ribs and sausage, and other various sides.

Yunnan-style Lahpet Salad (茶叶豆). Top center. If you’re familiar with Burmese cuisine at all, you might be familiar with their famed Lahpet — fermented tea leaves. West Yunnan also makes use of this iconic Burmese ingredient, mixing with tomato, fresh chilis, deep fried split pea, and a non-insignificant quantity of shredded cabbage.

Achang People’s ‘Crossing the Hand’ Rice Noodle (阿昌族过手米线). Top right. The Achang people are a small ethnic group living on the border with Myanmar, centered around the small town of Husa. While the group is most famous for their knife making, their “crossing the hand rice noodle” has become a relatively popular item in the border town of Dehong. It’s eaten by assembling a bite of rice noodle together with various toppings within your palms, a bit reminiscent of how Khanom Chin is enjoyed in pockets of Thailand. The rice noodle itself is made with local red rice, the sauce made with finely chopped grilled meat and pea noodle jelly. It’s also served with “sour water”, made by fermenting rice water and daikon leaves.

Xidoufen porridge (稀豆粉). Bottom left. A thick porridge made from dry split peas (same pea as the wandoufen noodle jelly above), xidoufen is a much-beloved breakfast item in the area. Usually topped with garlic oil, toasted peanut and sesame, and sour pickled mustard green. It can be seen served with rice noodles (pictured), or without. Often served alongside youtiao deep fried dough stick.

Fried Banana Blossoms (炒芭蕉花). Bottom center. A common ingredient in Yunnan’s warmer southern and western climate zones, banana blossom can be eaten in various ways. Pictured here is one stir fried with the area’s fermented soy bean cake and chili - absolutely awesome to devour alongside white rice.

Sour Vegetable Soup (酸扒菜). Bottom right. Variants of ‘sour vegetable soup’ can be found throughout the Tai-Kradai world all the way from Yunnan to Lanna in North Thailand. The west Yunnan style braises vegetable together with potato and sour fermented longbeans.

Pu’er-Sipsongpanna

Representative dishes:

Dai-flavor Salads (傣味凉拌). Left. Echoing their linguistic brethren south of the Chinese border, the Yunnanese Dai people love their pounded, mixed cold dishes — seasoned, of course, with vociferous quantities of chili, garlic, and lime. Over the years, their cold salads became a hit with both tourists and local Han Yunnanese… beginning to take on some Sichuan influence, such as the inclusion of a sort of Sichuan-adjacent red chili oil. Extremely common in markets throughout Yunnan nowadays, the chicken feet version is the OG variant that sparked the popularity.

Baoshao Grilled Meat (包烧肉). Center. ‘Baoshao’ refers to Dai cooking method whereby ingredients are wrapped in leaves and grilled to steam the contents. Practically anything can be ‘baoshao’d’, from from meat, to veg, to organs, to mushrooms, to tofu. Pictured is a baoshao of meat mixed with various herbs and chili.

Sa (撒). Right. Sa is a type of watery dip. In Yunnan, it’s often made by mixing finely minced herbs (Chinese chives, laksa leaves, culantro, etc) with pounded or minced meat (e.g. beef, pork, or fish), and then eaten with thin rice noodles. Bitterness is a highly valued flavor in Sa, thus you can also see Sa made from bitter fruit or the aforementioned half digested herb from cows. That said, more popular among non-Dai people in Yunnan tend to be the sa that lean instead into the sour: pictured here is a Sa made with lemon and beef.

Honghe

Representative dishes:

Hani People’s Grilled Fish (哈尼烤鱼). Left. The Hani people lives among the treacherous Ailao portion of the Hengduan range, where they built the UNESCO-famous rice paddy terraces. And within those gorgeous rice terraces, fish grow in the ponds right alongside the rice. One common way to enjoy this fish is grilling - pictured is a saucier version as you might see it at restaurant outside of the area, but in Honghe proper it’s often seen drier, with less sauce and oil.

Dipping sauce Chicken (蘸水鸡). Center. An important festival dish to the Hani people - this dish is (as the name suggests) much more about the dipping sauce than the bird itself. Pictured is a dipping sauce made by mixing a bevy of local herbs, cooked chicken blood, giblets, liver, stomach, intestines, and hard boiled eggs.

Peanut Milk Soup (花生汤). Right. Peanut milk is a common savory soup base throughout South Yunnan. The peanut is often ground directly with skin on, giving the soup its signature mauve color. It’s popular to use this as a base for a vegetable dish (pictured), but it can also be mixed with rice noodles and consumed as a breakfast.

Dali

Representative dishes:

Acid Set Cheeses (乳饼). Left. Produced in a similar fashion to paneer, Yunnan cheese consists of goat milk or cow milk and is coagulated with fermented whey. There’s various ways the dish can be eaten, but one classic choice is panfry and serve with Xuanwei ham.

Lentil Liangfen (鸡豆粉). Center. Produced similarly to the wandoufen in Han Yunnan discussed above, albeit using a type of local lentil in place of splitpea. It can be served stirfried, or as a cold dish. Pictured is one with blanched Chinese chive, carrot, and pounded peanuts, all drenched in a spicy vinegar-based sauce.

Suanmugua fish (酸辣鱼). Right. Throughout the Southeast Asian Massif and Tai-Kradai world, much of the food seems to leans on some sort of local ‘sour fruit’ — whether it be Tamarind, Makok, Makrut, or Lime. In Yunnan, the sour fruit of choice is Chinese quince. It can be fresh or dried. Pictured is a Dali classic of freshwater fish from the Erhai Lake braised with chili and the incredibly sour Chinese quince.

The Tibetan Plateau

Tibet. What’s there to say? The very name is evocative of the distance, a traveling destination with a borderline spiritual heft to it. And not just for westerners — in the Chinese psyche, Tibet holds a similar place.

But whether from the direction of Los Angeles or Shanghai, what often gets lost in the romanticism is that Tibet is a… real, actual place. With real, actual people living there, and doing so in an unfathomably harsh environment.

I highly suggest traveling to the Tibetan plateau. You may have heard that it’s difficult for foreigners to travel to Tibet, and it’s true that movement within the Tibet Autonomous region is restricted (possible, but restricted). And yet, the administrative region of “the Tibet Autonomous region” really only consists of the western half of the Tibetan cultural zone, which I would personally center more around Qamdo — extending eastward to Garzê and Ngawa in what’s administratively Sichuan, south to Dêqên in Yunnan, west to Lhasa, and North to Gyêgu (Yushu). Yushu is where I personally centered my time there traveling, and is highly recommended.

Food wise, however, I think it’s reasonable to right-size some expectations. Often I hear people in the west talk wistfully about Tibetan cuisine, impressions quite often laced with quite a bit of exoticism. I cringe a little inside when I see hipster fusion bars in America label their sriracha-laced dumplings as ‘Momo’ on their menus. Survival on the plateau is no joke, and Tibetan cuisine does an incredibly admirable — tasty, even! — job in aiding that project.

Representative dishes:

Tsampa (རྩམ་པ/糌粑). Top left. A staple grain of roasted barley flour that’s eaten in a number of ways - sometimes practically straight, simply mixed with a bit of water.

Gyuma, Blood Sausage. Top right. A blood sausage traditionally made from the let blood of an unkilled Yak, mixed with Tsampa as a filler.

Momo (མོག་མོག/馍馍). Bottom left. Traditionally stuffed with a bit more humble fare like potatoes, as time goes on Tibetan Momo seem to have taken on an increasingly dumpling-like identity. In neighboring Nepal, you can find interesting fusion-y applications like Momo served in various Northern Indian curries, a practice that’s also been replicated in various tourist haunches in China.

Tibetan Butter Tea (བོད་ཇ/酥油茶). Bottom right. At times a bit of an acquired taste, Butter tea is a mixture of brewed Yunnanese Pu’er, freshly churned yak butter, and salt.

Sichuan and Chongqing

Sichuan is a regional cuisine that is quickly becoming a national one. If you were walking in blind to a random restaurant anywhere in China these days, the probability that it’d have at least some Sichuan fare somewhere on their menu might be roughly 50/50.

It’s a cuisine forged on migration. In-migration from the resettlement of Sichuan, Chongqing’s role as the wartime capital, and its historical status as a breadbasket in China; out-migration during China’s post ‘78 boom as Sichuan people streamed to the coast to look for work.

But also during the 1980s, something else happened - Sichuan cuisine was actively standardized, promoted, and commercialized by the province’s local culinary associations. The Sichuan restaurant became an ecosystem that could be bought into - not quite a turn key operation, but almost. If you’re someone with a little bit of money, a desire to open a restaurant, and no direct F&B experience, you have two logical not-hotpot paths to follow: the Cantonese restaurant, and the Sichuan restaurant. Recipes and menus are widely available for purchase. Equipment is standardized. Training is standardized. It’s certainly no accident that these are the two cuisines most available outside of China as well.

But it should be noted that within the modern restaurant environment, there ended up being a bit of a mishmash effect. Dishes seemed to be selected from around Sichuan, but in the province itself, there tends to be much more regionality.

Sichuan chefs tend to divide Sichuan cuisine into three schools. The Upper River Gang (上河帮) is centered around the Chengdu plain, and so (predictably) the cities of Chengdu, Meishan, and Leshan. Many of the classic Sichuan dishes that you know and love originally hail from this area - Mapo Tofu, Twice Cooked Pork, Kung Pao chicken, etc.

The Lower River Gang (下河帮) was borne out of the gritty trading towns that dot the upper reaches of the Yangtze river, and is centered around Chongqing. If the Chengdu is wing #4 on the Hot Ones gauntlet, Lower River is wing #7. Much more comfortable in the upper reaches of the Scoville scale, lower river Sichuan might conform a bit closer to the international stereotype of Sichuan cuisine as fuck-you-level-spicy.

In the south of Sichuan there is the Salt Gang (盐帮菜) school, whose name might take a touch of explaining. Historically, salt was a precious commodity in China, and the city of Zigong was a major epicenter of the trade during the Qing dynasty. The ‘gang’ (帮) in these three cuisines refer to the merchant groups that controlled various reaches of the Sichuan river system, and the Salt Gangs controlled the area around Zigong, Luzhou, and Yibin - and did develop their own cuisine.

Still, in modern times, the Salt Gang shares some philosophical similarities to the Upper River, so could perhaps be lumped together if you were feeling lumpy.

In the south of Sichuan, however, there’s a lesser known little ‘nub’ that juts down into Yunnan, centered around Xichang. This area is perhaps a little more similar to food in Yunnan than it is Sichuan proper, being heavily influenced by Yi people food (and so we called Yi Sichuan).

Upper River Gang

Representative dishes:

Kungpao Chicken (宫保鸡丁). Top left. Sichuan cuisine classically consists of 15 flavor profiles (or alternatively up to over 30, depending on who you ask), Kungpao is functionally one of them: the Hula ‘toasted spicy’ (煳辣) flavor profile. Characteristic to this flavor profile is to fry the dried chili until almost burnt for a deep toasted fragrance. The dish has many, many schools, but the most common add-ins include Chinese leek and deep fried peanuts.

Chili Oil Wonton Soup (红汤抄手). Top center. Wontons are called ‘chaoshou’ (抄手) in Sichuanese cuisine - they can be dry (i.e. mixed with chili oil) or wet (i.e. in soup, also with chili oil). Pictured is the wet variant, but the dry version is the most ubiquitous.

Twice Cooked Pork (回锅肉). Top right. Like Kungpao chicken, twice-cooked pork is one of those classic dishes that everybody has opinion on. Consisting of stir-fried boiled fatty pork - the specific cut is a matter of great debate - the foundational flavors of the dish are the a mix of Sichuan chili paste (Pixian Doubanjiang) and green garlic.

Mapo Tofu (麻婆豆腐). Bottom left. Finishing the trifecta of “Sichuan dishes that everyone has an opinion on”, Mapo Tofu has a long and varied history but at its core belongs to the mala spicy and numbing flavor profile. The dish consists of tofu simmered in a broth of crispy minced beef, Sichuan chili bean paste, chili powder, and finished to taste with Sichuan peppercorn power.

MSG Noodles (味精素面). Bottom center. A street food classic from Leshan city south of Chengdu. This mixed noodle highlights the use of MSG, which was considered a new and novel ingredient at the time of the dish’s invention (the 1940s). Mixed in are also the Sichuan noodle usual suspects of chili oil and yacai - fermented mustard green.

Zhangcha Smoked Duck (樟茶鸭). Bottom right. A classic smoked duck in Sichuan that’s made by marinating, cold smoking with camphor and tea, steaming, and then finally deep frying the duck. There’re some argument around the name ‘Zhangcha’, one side believing that the zhang refers to the camphor (樟树) that's used for smoking, and the other believing that it refers to using tea from Zhangzhou (漳州). Our vote goes for the former.

Lower River Gang

Representative dishes:

Wanzhou Grilled Fish (万州烤鱼). Left. A dish that’s spread far and wide from its origins in Wanzhou city, this grilled fish has become a late night BBQ staple in all four corners of the country. It’s made by grilling marinated fish over charcoal, then bringing to the table in a bath of chili and spice ladened sauce - braising slowly over a small fire as you munch on it. While you can find various choices like pickled chili and ‘sauce flavored’, pictured is the classic – “mala”, numbing-spicy flavor.

Maoxuewang (毛血旺). Center. A spicy dish with a name that’s confused non-Sichuan people and auto-translate servers alike. It means cow stomach (mao refers to tripe, i.e. maodu, 毛肚) and blood (xuewang, 血旺, is Sichuan dialect for congealed blood cake). Originally it was simply just organ and blood cooked in a numbing chili broth, but over time became increasingly loaded with ingredients like spam, potato, tofu, etc.

Chongqing Hotpot (重庆火锅). Right. A Sichuanese dish since become a national and even international sensation. It was originally a humble dish that leaned on cheap beef and chili bean paste… it’s since reached the dizzying heights of the Scoville scale, the hotpot version of Da Bomb, a rite of passage, and a cultural institution.

Salt Gang

Representative dishes:

Tofu rice (豆花饭). Top left. Throughout Sichuan and Guizhou, around lunchtime you can find people streaming into their tofu rice joints - enjoying a savory douhua ‘tofu pudding’ over rice together with various chili-laced dipping sauces. The Sichuanese South is particularly famed for their love of this tradition, with localized dipping sauce variants such as the Fushun version (laced with Chinese patchouli) and the Luzhou version (brightens things up with mujiangzi oil).

‘Cold eaten’ Beef (冷吃牛肉). Top center. Thinly sliced beef that’s deep fried until dry and jerky-like and soaked in chili oil. Popular as a restaurant dish, a snack for the road, and goes phenomenally with the local area’s baijiu liquor.

Yibin Burning Noodles (宜宾燃面). Top right. Originally a humble meal for Yibin dock workers, it consists of chili oil, toasted peanuts and sesame, and Yibin yacai. The ‘burning’ in the name is a translation of the character ran (燃), which means ‘to ignite’. There’s various theories on why a mixed noodle would include such a character - the most oft-repeated one is that is was differentiating the noodle as a ‘not-soup-noodle’ dish. That is, that the noodle was not just dry (so, convenient to eat on the docks), but so dry that you could theoretically toss it over a fire and the thing would ignite. Of course, most modern Burning Noodles prove quite stubbornly difficult to set on fire…

Shuizhu Beef (水煮牛肉). Bottom left. A.k.a. “boiled beef” or “chili poached beef”, this is a dish that these days is seen through Sichuan - together with the country at large. The dish comes from the area’s history of salt production, and the oxen that were used as manual labor in the process. The dish was originally a way to use up this tough meat - salt marinated, coated in a generous quantity of sweet potato starch, all poached in a broth heavily seasoned with chili and Sichuan peppercorn.

Fresh Chili Rabbit (鲜椒兔). Bottom center. Rabbit is a popular protein source throughout Sichuan (Chengdu is famed for their snack of spicy rabbit heads). Pictured is a Zigong rabbit dish cooked with fresh chilis, Sichuan pepper, and baby ginger.

Crispy meat soup (酥肉汤). Bottom right. Surou - ‘crispy meat’ is deep fried pork by any other name. Preferably made with fatty pork, it deep fries with a seasoned egg/sweet potato starch batter. It’s an ingredient that can be purchased directly from the market in Sichuan, and there’s various ways that they’re incorporated into meals. Those outside of Sichuan are often introduced to the ingredient as a choice on Chongqing hotpot menus, but in South Sichuan home cooks often like to employ it in quick soups. Pictured is one such soup with pea shoots.

Yi Sichuan

Representative dishes:

Tuotuorou (坨坨肉). Left. Traditionally a festival dish for the Yi people, the name literally means ‘chunky meat’. It can be produced from various meats (pictured is pork), cut into large hunks, and simmered together with a mix of salt, Sichuan pepper, chili, and mujiangzi.

Bitter Buckwheat Baba (苦荞粑粑). Center. Bitter buckwheat (苦荞), a sort of buckwheat that grows well in mountainous terrain, is one of the staple grains of the Yi people. Pictured is a leavened pancake made from this grain.

Yi-style Barbecue (彝族烧烤). Right. While many BBQ styles throughout China lean heavily on various spice mixes, Yi style barbecue focuses more on the ingredients themselves. Pictured is one style whereby ingredients are grilled communally on long skewers over a central charcoal fire.

Hubei

Hubei cuisine is simultaneously underrated, and yet difficult to parse. Poking around the province, there’s undeniably a ton of city-by-city diversity - Wuhan is famous for their breakfast snacks like Hot Dry Noodles (as well as this stuffed Shaomai which might just be one of the best things I’ve ever eaten), Xiangyang is famous for Beef Noodles, and Jingzhou is famous for their Guokui Crispy Pancakes (荆州锅盔).

And yet, all these cities do seem to cluster around certain concepts - beef and fish, steams and braises, a love of the chili pepper, and a rich culture of baijiu drinking at breakfast. Someone more educated on Hubei cuisine than us would likely be able to parse at least a couple of internal divisions, but outside of a brief trip or two to Wuhan, we’re still woefully undereducated.

The one bit that is undeniably a bit different is the mountainous Tujia area around Enshi in the west of the province, which we opted to lump with the similarly mountainous western section of Hunan to the south.

Representative dishes:

Hot Dry Noodles (热干面). Top left. The lifeblood of Wuhan - this noodle dish can be a snack, it can equally be breakfast. Classically a mix of sesame sauce, the braising liquid from Hubei-style beef master stock, chili sauce, and spicy preserved radish.

Doupi Pancakes (三鲜豆皮). Top center. A dish that it seems everyone in Hubei has an opinion on. The yellow ‘sheet’ on top is a sheet of cooked mung beans with egg cracked over it, covering the various fillings - sticky rice, shiitake mushroom, marinated pork, and tofu jerky, among others - below.

Hubei fishcakes (湖北鱼糕). Top right. With the Yangtze flowing down the center of the province and many lakes dotted about, a penchant for freshwater fish is incredibly characteristic of the Hubei province. One very classically Hubei dish is their fish cake, which is made by steaming fish paste and finishing with an egg yolk wash, giving the cake its signature vibrant yellow hue. A must around Chinese New Year in Hubei, it’s an ingredient that can be purchased at the market and then used in various applications - e.g. braises, hotpots, or steamed (pictured)

Beef Noodles (襄阳牛肉面). Bottom left. A dish that bears a bit of resemblance to Sichuan’s Red Braised Beef noodle soup next door, Xianyang’s beef noodles are a somewhat simpler affair which lean heavier on beef - loading up with a generous quantity of sliced beef, and serving in a rich beef broth.

The Three Steams of Mianyang (沔阳三蒸). Bottom center. The ‘three steams of Mianyang’ refer to a mix of fish, meat, and vegetable that’s coated in a spiced rice flour, ala Rice Powder Pork Belly. In the foreground is the similarly classic Hubei steamed dish, ‘Pearl Meatballs’, which are coated with sticky rice.

Deep Fried Lotus Root (干煸藕丝). Bottom right. Lotus root is an ingredient particularly abundant in Hubei, and appears in many forms. One of the most classic soups of the province is Lotus Root and Pork Rib Soup; pictured is a popular drinking snack of crispy deep fried lotus sticks seasoned with chili and Sichuan pepper.

Hunan

If there is one contender to Sichuan cuisine as ‘the national cuisine of China’, it’s probably Hunan food. With working class eateries dotting the country and a strong influence on workplace canteens, makes for a strong challenger.

Put simply, Hunan cuisine proper - which we’ll refer to here as its formal name Xiang - is perhaps the world’s greatest conspiracy to consume unrelenting quantities of white rice. Practically to the dish, it’s so good with rice. When I was the younger workout-bro carb-avoidance version of myself… I didn’t quite ‘get’ Hunan food. But that was clearly because I was doing it very, very wrong.

In addition to being strong seasoned, you’ll notice how ‘finely minced’ a lot of Hunan dishes are. That’s no accident. How Hunan food is best enjoyed, in my current opinion:

Get a big container of rice.

Top, mix, or alternate bites of said rice with your dishes of choice.

Go along for the ride, interspersing it all with a tall bottle of beer or a grown-up-sized class of baijiu.

Meanwhile, in the mountainous Hunan West, you’re starting to get into a cuisine that - like neighboring Guizhou - is quite influenced by the ethnic groups in the area. And perhaps befitting our personal love of Guizhou cuisine, we personally can’t help but be drawn to that section of the province (which is also stunningly gorgeous in parts).

Xiang

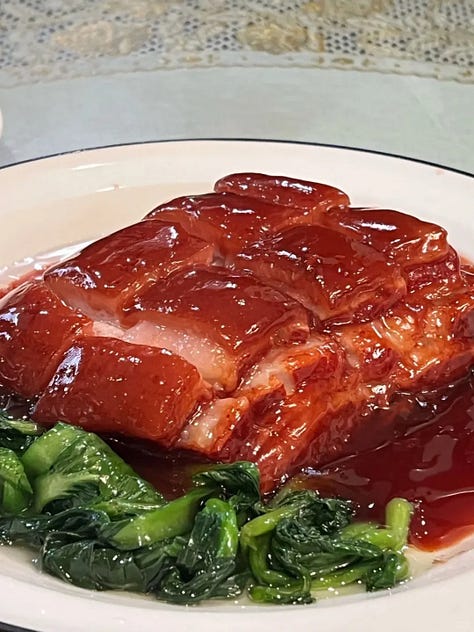

Hunan-style Red Braised Pork (红烧肉). Top left. Red Braised Pork is a dish that you can find variants of in practically every pocket of China. The Hunan version insists on starting things with a tangse caramel, and often includes chili pepper in the spice mix. Allegedly Mao Zedong’s favorite dish, ‘Mao-style’ is an elegant banquet presentation of the dish; pictured is a more rustic style which includes lightly fermented soybeans.

Chili Fried Pork (辣椒炒肉). Top center. While many provinces have variations on the theme, Hunan’s is the most iconic. Stir fried pork with spicy chilis - pretty much does what it says on the tin.

Stir Fried Smoked Bamboo Shoots & Chinese Bacon (烟笋炒腊肉). Top right. A dish that packs a real punch of smokiness - cold-smoked bamboo shoots with Hunan style ‘Chinese bacon’, stir fried with chilis and aromatics.

Golden Coin Eggs (金钱蛋). Bottom left. Hard boiled eggs, sliced, then lightly coated with cornstarch and shallow fried. Finished by stir-frying with chili, aromatics, and Hunan’s local variant of Chinese fermented black soybean.

Tea Tree Oil Fried Chicken (茶油鸡). Bottom center. ‘Tea tree oil’ - i.e., camellia oil - is a highly valued cooking oil in Hunan, traditionally reserved for special occasions due to limited yield. While stocks are less limited nowadays, it still tends to be reserved for specific dishes (which are also sold at a slight premium). Pictured here is a ‘free range’ chicken fried in tea seed oil, a classic application.

Fish Rice Noodle Soup (鱼粉). Bottom right. In additional to being incredibly rice centric, Hunan is also a province famed for its rice noodles. Outside Hunan, the most iconic Hunanese rice noodle dish is likely Changde Beef Rice noodles, but pictured is my personal favorite of Fish Rice Noodle soup - specifically the Hengyang version. Found in various pockets around Hunan, the dish consists of rice noodles cooked in with a quick, chili-laced milky fish broth.

Hunan West

Blood Duck (血鸭). Top left. Blood duck is a dish that you can find throughout Hunan and even down into the north of Guangxi. Pictured is a Hunan West variant which stir fries and braises duck with chili and ginger, finishing the dish with fresh blood to create an emulsified sauce.

Pounded Chili Dip (擂辣椒). Top center. A simple and delicious dip tantalizingly evocative of Northern Thailand. Pictured is a dip of roasted chili and tomato, which is then pounded and mixed with cilantro. Fantastic to eat over rice.

Guoba Sandwich (湘西锅巴). Top right. If you’ve ever wondered if you could fashion a dish to consist solely the crispy rice found at the bottom of a Paella or a Claypot rice — and then took that and turned it into a sandwich with various chili-laced fillings — Hunan West has your answer. “The Socarrat Sandwich” is just as delicious as it sounds, and our recipe on the thing is probably my favorite video we’ve put out.

Mungbean Noodles (锅巴粉). Bottom left. Classic to the area, Mungbean noodles are made by forming a batter with mungbean flour, frying it into a pancake, and then slicing it into noodles. Served in various forms, pictured is the noodle served in soup together with a bevy of toppings.

Fried Bee Larvae (炒蜂蛹). Bottom center. Deep fried insects are commonly seen throughout China, particularly in the mountainous regions. These days often ordered as a drinking snack, pictured is bee larvae fried with chili and deep fried peanuts.

Pickled Radish ‘Snack Bar’ (芷江酸萝卜). Bottom right. A street food classic in Hunan West, the foundation of the snack is the titular sour fermented daikon. You then select various pickles, vegetables, and tofu products, which are then all mixed together with a chili oil-based sauce.

Jiangxi

When I lived in Shenzhen, I’d often meet people from Jiangxi - after all, demographically, Shenzhen is predominantly a mix of Hunan, Chaozhou, Sichuan, and Jiangxi people (any Cantonese influence tends to come from Hong Kong weekenders next door).

Sichuan people are quite proud of their food. Ditto with Hunan and Chaozhou. But when I would ask people from Jiangxi about their cuisine, the common response would be:

“Jiangxi doesn’t have a cuisine”.

…which was a statement that always sort of confused me.

Now, certainly, if you look at the make-up of an average Jiangxi meal, what you tend to find is a food bit of crossover with to the neighboring Hunan province: chilis, small minces, a mass of white rice, all punctuated with a love of the rice noodle. And given Hunan cuisine’s dominance among country’s working class canteens and eateries, I could easily imagine someone from Jiangxi coming to an opinion of “Well, this is just… how people eat.”

And it would be fair, maybe, to lump much of Jiangxi in with Hunan. But given that there’s a number of dishes (proudly) unique to the province… you’d then, I think, have to refer to the whole thing as Hunan-Jiangxi food. A bit of a mouthful, and we’re more splitters anyway.

In the Northeast of the province, however, the mountains are starting to get undeniably different than the lowlands around the capital of Nanchang. This is the home of the famed porcelain town of Jingdezhen, and the food there shares quite a bit with the similarly mountainous area of Zhejiang next door.

In the south of the province, around the city of Ganzhou, things are starting to get rather quite Hakka. A difficult area to categorize. Less of a blending of food, a bit more Jiangxi and Hakka both living together in the same city.

Jiangxi

Representative dishes:

Spicy Chicken Feet (辣鸡爪). Left. Homecooking classic of soft braised chicken feet, seasoned with fermented rice and a preponderance of chili.

Jiangxi Chili Fried Rice Noodles (江西炒米粉). Center. Jiangxi, like Hunan, is quite famous for their rice noodles - outside of China, perhaps the many people’s introduction to the province are the dried rice noodles that bear its name. Pictured is a street snack that’s ubiquitous in Jiangxi: stir fried rice noodles with chili and baby bok choy.

Clay Jar Soups (瓦罐煨汤). Right. Perhaps the most iconic sight outside of a Jiangxi restaurant is a massive, human-size clay jar. Inside are smaller jars, as pictured, steamed inside to create the province’s famed double boiled soups. This is one with pork meatball and century egg.

Northeast Jiangxi Mountains

Representative dishes:

Qigao Pancake (汽糕). Left. This local street food consists of a thin layer of fermented rice batter, topped with dried (and reconstituted) bamboo shoots and daikon. Brushed with fermented bean sauce before serving.

Dengzhanguo (灯盏粿). Middle. Dengzhanguo is made by first steaming a rice cake into a ‘lantern-shaped’ little bowl, filling with mushroom, pork, beansprouts, and bamboo shoots, and then steaming the package again. Traditionally a festival dish, it’s now often enjoyed as a street snack.

Acorn tofu (苦槠豆腐). Right. Made from the acorn of the Chinese Tanbark Oak (苦槠), this is a dish that comes from a history of starvation food and can be found in various mountainous pockets throughout South China. The acorns are soaked for weeks, then ground, strained, and cooked down into a jiggly rice cake-like object. Pictured is one chopped up and served with fresh chili and scallion.

Fujian

Eating around Fujian, there was always a certain je ne sais quoi that reminded me of Chinese food in America, and certainly Chinese food in Malaysia and Singapore. The former is subtle, and (assuming that it’s not just in my head) likely came by the way of Taiwan - after all, Taiwanese immigrants in the 70s and 80s were instrumental in crystallizing what we know of today as ‘American Chinese takeout’.

The latter, however, is no puzzle: merchants and settlers from South Fujian - Minnan, or Hokkien - were one of the three major pillars of maritime Chinese in South East Asia (along with the Cantonese and the Teochew, discussed above).

Once upon a time, the city of Quanzhou was the nexus of maritime trade in Asia, visited and written about both by Marco Polo and Ibn Battuta. Food wise, I’m personally probably guilty of being overly drawn to the faint echo of those pathways, but most Minnan people would likely point you more to their famed oyster omelettes instead.

Minbei, the north section of Fujian around the capital city of Fuzhou, is quite distinct from the south. Sweet and sours feature prominently, ditto with the red dregs from fermented rice wine, called hongzao.

The food from the West Fujian Mountains became quite popular in Fuzhou in the 80s and 90s, and expanded throughout China in the form of the chain “Shaxian snacks” - Shaxian referring to a small mountain town particularly famed for their food. If you’ve eaten around China, it’s quite likely that you’ve stumbled into one at some point. The chain is a reasonable representation of western Fujian food, but quality-wise (obviously) pales in comparison to what you can find in the region itself.

Minnan

Representative dishes:

Xianfan (咸饭). Top left. A festive rice dish that, in essence, is cooked pilaf-style. Rice is fried in a base of lard, pork, dried shrimp, dried shiitake and shallot, then water is added and the entirety of the pot is steamed.

Shacha Noodles (沙茶面). Top center. Shacha sauce - a mix of peanut, fish sauce, shallot, chili, sesame, spices, and oil - is thought to have derived from Southeast Asian Satay sauce (though given Satay’s Hokkien linguistic roots, directionality’s hard to determine). The sauce can be used as a flavor base for stir fries, braises, and hotpots - pictured is a noodle soup common in Minnan served with beef and tofu puff.

Curry Beef (咖喱牛排). Top right. An old school dish from Quanzhou, these braised beef ribs are another example of a shacha-based dish, albeit one with (interestingly) curry powder also added to the mix. Thought to have originally been a Hokkien Muslim dish.

Mianxianhu (面线糊). Bottom left. Mianxianhu is made by cooking a gossamer-thin noodle in a soup together with seafood and pork, which ends up to dissolving into an almost congee-like consistency. Classically eaten as a breakfast or a midnight snack, it’s commonly paired next to some youtiao deep fried crullers.

Minnan Oyster Pancake (海蛎煎). Bottom center. A much beloved snack in the area, the traditional Minnan version is a bit more of an acquired taste than the Teochew variant next door. The pancake tends to be egg-less and leans heavily instead on sweet potato starch to arrive at a chewy, gloopy consistency. Often served next to Minnan’s local sweet chili sauce (甜辣椒酱).

Thick Beef Soup (牛肉羹). Bottom right. Thick starch-thickened soups, geng, are quite popular throughout the region, with beef geng likely being the most classic. A very old school dish, beef slices are coated with a generous quantity of sweet potato starch and poached in beef stock - a process that gently cooks the beef, while thickening the soup in the process.

Minbei

Representative dishes: